By Maryann Readal

The Herb Society’s Herb of the Month for May is lavender, Lavandula angustifolia, which is one of almost 50 species of lavender (Blankespoor, 2022). It is also called Lavandula officinalis and English lavender, although it is not native to England. Lavendula angustifolia is native to countries surrounding the Mediterranean. L. angustifolia is the species most used for medicinal and culinary purposes. The word lavender is derived from the Latin word “lavare” which means to wash. It is an herb that prefers a sunny, dry climate and is the most winter hardy lavender, growing as an annual or a perennial depending on your growing zone. It can be propagated by taking cuttings in the fall or spring. There are many cultivars of Lavandula angustifolia including ‘Hidcote,’ ‘Munstead,’ and even one called ‘Susan Belsinger’ named for The Herb Society’s award-winning herbalist, author, and recent Honorary President.

Lavender is an herb that has been used since antiquity. The Egyptians used it as a perfume and also in the mummification process. It is believed that the politically savvy Cleopatra seduced Marc Antony and Julius Caesar with the fragrance of lavender. “Phoenicians and other ancient peoples of Middle Eastern regions used lavender for bathing and making their homes smell fresher” (Lawton, 2010). Hippocrates is credited with saying “the key to good health rests on having a daily aromatic bath.” Medieval and Renaissance washerwomen were called “lavenders” because they spread their laundry over lavender bushes to give the laundry a nice fragrance (Leigh, 2022).

In the 1st century A.D., Dioscorides, a Greek physician to the Roman army, recommended lavender for its antiseptic qualities. He wrote that taken internally, “lavender would relieve indigestion, sore throats, headaches, and externally clean wounds” (Perry, 2019). It was also used to “disinfect sick rooms in Persia, Greece and Rome” (American Botanical Council, N.D.). In Malaysia, lavender oil combined with peppermint and eucalyptus oil was used as a topical medicine that promised to cure minor aches and pains. It was called White Flower Oil and its use as an analgesic balm is still popular today. Traditional folk medicines still use lavender essential oil to treat inflammatory illnesses and anxiety.

In the 1st century A.D., Dioscorides, a Greek physician to the Roman army, recommended lavender for its antiseptic qualities. He wrote that taken internally, “lavender would relieve indigestion, sore throats, headaches, and externally clean wounds” (Perry, 2019). It was also used to “disinfect sick rooms in Persia, Greece and Rome” (American Botanical Council, N.D.). In Malaysia, lavender oil combined with peppermint and eucalyptus oil was used as a topical medicine that promised to cure minor aches and pains. It was called White Flower Oil and its use as an analgesic balm is still popular today. Traditional folk medicines still use lavender essential oil to treat inflammatory illnesses and anxiety.

English lavender is used in aromatherapy because of its relaxing properties. ”Research supports the calming, soothing and sedative effects of lavender when inhaled” (Amidon, 2013). In traditional Chinese medicine it is called “the broom of the brain” because of its effectiveness in treating sleep disorders (Luo, 2022). Its fragrance and relaxing properties makes it an essential ingredient in sachets and potpourris.

English lavender is used in aromatherapy because of its relaxing properties. ”Research supports the calming, soothing and sedative effects of lavender when inhaled” (Amidon, 2013). In traditional Chinese medicine it is called “the broom of the brain” because of its effectiveness in treating sleep disorders (Luo, 2022). Its fragrance and relaxing properties makes it an essential ingredient in sachets and potpourris.

Because the flowers and leaves were fragrant and deterred insects, lavender was used as a strewing herb in the Middle Ages. It was also used to deter evil and Christians hung crosses woven with the plant in doorways to protect their homes. It was also used as an aphrodisiac. Some say that lavender’s use can be traced back to biblical times, claiming that the “spikenard” referred to in the Bible was lavender. However, some researchers say that the biblical “spikenard,” which may have looked similar to lavender, was actually the very fragrant plant Nardostachys jatamansi, which is in the honeysuckle family and grows in the Himalayas.

Lavandula angustifolia is the lavender that is used in cooking. Lavender flowers are a part of the French seasoning, herbes de Provence. Lavender flowers are often added to cakes and cookies, jellies, beverages, and salads. They have a strong flavor, so using a little is usually enough. Rubbing potatoes with lavender essential oil helps to keep them from sprouting (Abd El-Kader, 2016).

Lavandula angustifolia is the lavender that is used in cooking. Lavender flowers are a part of the French seasoning, herbes de Provence. Lavender flowers are often added to cakes and cookies, jellies, beverages, and salads. They have a strong flavor, so using a little is usually enough. Rubbing potatoes with lavender essential oil helps to keep them from sprouting (Abd El-Kader, 2016).

Lavender is a wonderful plant in the garden. Release its essential oil by rubbing lavender leaves on your skin to help keep mosquitos and other insects at bay while working among your plants. Plant it along pathways where brushing against the leaves will release its fragrant aroma. Lavender attracts bees, butterflies, and other pollinators to your garden. There are many good reasons to plant lavender, even if it is for only a single season.

Throughout history, lavender has been associated with love and romance and has been a part of wedding traditions. Love and lavender is evidenced in the 1980’s “Lavender’s Blue” song from Tim Hart and Friends as sung in the 2015 movie, Cinderella: (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ow25lvYoKXo).

Lavender’s green dilly, dilly,

Lavender’s blue,

If you love me dilly, dilly

I will love you.

It’s interesting to note that this song has its roots in an old English song from the 1600s, “Diddle, Diddle, Or the Kind Country Lovers.”

For more information about lavender, please visit The Herb Society’s Essential Facts for Lavender: https://www.herbsociety.org/file_download/inline/149725a4-88ed-4244-86bf-8507e18daa53

Medicinal Disclaimer: It is the policy of The Herb Society of America, Inc. not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health use. This information is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an endorsement of any particular medical or health treatment. Please consult a health care provider before pursuing any herbal treatments.

Photo Credits: 1) Lavandula angustifolia (WC Sten Porse, via Wikimedia Commons); 2) Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra (Sir Lawrence Alma Taderma, public domain); 3) White Flower Oil (Hoe Hin Pak Yeow Manufacturing); 4) Lavender sachets (Amazon); 5) Lavender field in France (courtesy of the author)

References

Abd El-Kader, A.E.S. et al. 2016. Using essential oils to decrease potato tubers sprouting, rotting and insect infestations during storage and ambient temperatures. Accessed 4/16/24. Available from https://jpp.journals.ekb.eg/article_47067_b3dfbf1bd4087a333ea5b65ca5c83bb0.pdf

American Botanical Council. N.D. Lavender flower. Accessed 4/8/24. Available from https://www.herbalgram.org/resources/expanded-commission-e-monographs/lavender-flower/

Amidon, Caroline. 2013. Essential facts for lavender. Accessed 4/9/24. Available from https://www.herbsociety.org/file_download/inline/149725a4-88ed-4244-86bf-8507e18daa53

Blankespoor, Juliet. 2022. The healing garden. Boston: Mariner Books.

Lawton, Barbara Perry. 2010. A love affair with lavender. Accessed 4/9/24. Available from https://ahsgardening.org/wp-content/pdfs/2010-05r.pdf

Leigh, Lex. 2022. History’s love of lavender: from mummies to bathhouses and beyond!

Accessed 4/19/24. Available from https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-ancient-traditions/lavender-history-0016704

Luo, Jing and Jiang Wubian. 2022. A critical review on clinical evidence of the efficacy of lavender in sleep disorders. Accessed 4/16/24. Available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35412693/

McCoy, Joe-Ann. 1999. Lavender: History, taxonomy, and production. Accessed 4/15/23. Available from https://newcropsorganics.ces.ncsu.edu/herb/lavender-history-taxonomy-and-production/

Perry, Nicollete. 2019. A love letter to lavender. Accessed 4/8/24. Available from https://www.healthline.com/health/lavender-history-plant-care- types#:~:text=The%20Greek%20physician%20to%20the,only%20relaxing%2C%20but%20also%20antiseptic.

Taliesin, David. 2021. Lavender: the great nard controversy. Accessed 4/8/24. Available from https://sabatsandsabbaths.com/2021/06/30/lavender-the-great-nard-controversy/

.

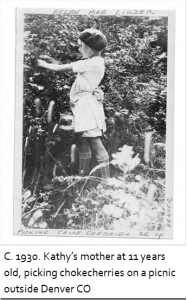

Springtime is my favorite time of year because the earth awakens and sends up green growing plants, which provide us with the first garden harvests: spring tonic weeds packed full of nutrients and vitamins. I do forage quite a bit on my own wherever I might be, however it is much more fun to herborize with friends. I co-teach a “Wild Weeds and Seasonal Greens” class with fellow herbalist, Tina Marie Wilcox. Some of the info in this intro, we co-authored together when collaborating on our classes.

Springtime is my favorite time of year because the earth awakens and sends up green growing plants, which provide us with the first garden harvests: spring tonic weeds packed full of nutrients and vitamins. I do forage quite a bit on my own wherever I might be, however it is much more fun to herborize with friends. I co-teach a “Wild Weeds and Seasonal Greens” class with fellow herbalist, Tina Marie Wilcox. Some of the info in this intro, we co-authored together when collaborating on our classes.  While I forage berries, roots, bark, seeds and nuts, I am concentrating on wild weeds, greens and flowers here. Wild, edible greens are powerful, good food and offer a variety of flavors for free. Wise gardeners and farmers the world over use many of the plants that have successfully colonized the soil as beneficial allies. This is in sharp contrast to modern landscape and agriculture methods that strive to completely control the species of plants growing on the land, regarding all volunteers as weeds.

While I forage berries, roots, bark, seeds and nuts, I am concentrating on wild weeds, greens and flowers here. Wild, edible greens are powerful, good food and offer a variety of flavors for free. Wise gardeners and farmers the world over use many of the plants that have successfully colonized the soil as beneficial allies. This is in sharp contrast to modern landscape and agriculture methods that strive to completely control the species of plants growing on the land, regarding all volunteers as weeds.  Also, it is good to be aware of the optimum time to harvest the different plant parts, noted by Rosalee de la Forêt and Emily Han in their wonderful book

Also, it is good to be aware of the optimum time to harvest the different plant parts, noted by Rosalee de la Forêt and Emily Han in their wonderful book  Methodically pull the tender leaves from the stems. Pinch off leaves with yellow edges, brown or black spots. Discard wilted, spoiled or badly bug-eaten leaves in the compost bucket. Place the edible parts in the vinegar water as you work and submerge the mass in the water, plunging up and down several times to loosen foreign matter. Let the greens soak in the water for several minutes and the grit will fall to the bottom of the container. Lift them out and drain them. Discard the vinegar water and spin or pat the greens dry; store these ready-to-eat greens in the refrigerator.

Methodically pull the tender leaves from the stems. Pinch off leaves with yellow edges, brown or black spots. Discard wilted, spoiled or badly bug-eaten leaves in the compost bucket. Place the edible parts in the vinegar water as you work and submerge the mass in the water, plunging up and down several times to loosen foreign matter. Let the greens soak in the water for several minutes and the grit will fall to the bottom of the container. Lift them out and drain them. Discard the vinegar water and spin or pat the greens dry; store these ready-to-eat greens in the refrigerator.

Susan Belsinger lives an herbal life, whether she is gardening, foraging, herborizing, photographing, teaching, researching, writing, or creating herbal recipes for the kitchen or apothecary—she is passionate about all things herbal. Referred to as a “flavor artist,” Susan delights in kitchen alchemy—the blending of harmonious foods, herbs, and spices—to create real, delicious food, as well as libations, that nourish our bodies and spirits and titillate our senses. There is nothing she likes better than an herbal adventure, whether it’s a wild weed walk, herb conference, visiting gardens or cultivating her own, or the sensory experience of herbs through touch, smell, taste, and sight.

Susan Belsinger lives an herbal life, whether she is gardening, foraging, herborizing, photographing, teaching, researching, writing, or creating herbal recipes for the kitchen or apothecary—she is passionate about all things herbal. Referred to as a “flavor artist,” Susan delights in kitchen alchemy—the blending of harmonious foods, herbs, and spices—to create real, delicious food, as well as libations, that nourish our bodies and spirits and titillate our senses. There is nothing she likes better than an herbal adventure, whether it’s a wild weed walk, herb conference, visiting gardens or cultivating her own, or the sensory experience of herbs through touch, smell, taste, and sight.

People have had a relationship with herbs for thousands of years. They are consumed as food or flavoring and act as normalizers supporting natural health.

People have had a relationship with herbs for thousands of years. They are consumed as food or flavoring and act as normalizers supporting natural health.  Studies have found that bee balm contains many active constituents: the phenol, thymol, which protects the plant from microbial and fungal infections and does the same when consumed by people; the monoterpene linalool, which has an odor that attracts pollinating insects and acts as an antiseptic; and beta-phellandrene, which has antioxidant actions in plants, protecting them from UV radiation and in humans can act as an expectorant to relieve catarrh (mucus) and promote productive cough.

Studies have found that bee balm contains many active constituents: the phenol, thymol, which protects the plant from microbial and fungal infections and does the same when consumed by people; the monoterpene linalool, which has an odor that attracts pollinating insects and acts as an antiseptic; and beta-phellandrene, which has antioxidant actions in plants, protecting them from UV radiation and in humans can act as an expectorant to relieve catarrh (mucus) and promote productive cough. Harvest nettles wearing gloves.

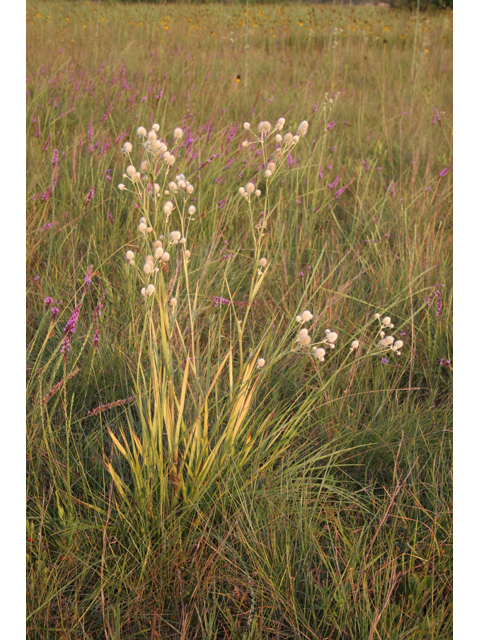

Harvest nettles wearing gloves. I first saw Eryngium yuccifolium Michx.—a.k.a rattlesnake master, button eryngo, or button snakeroot—planted at the Gene Leahy Mall, a park in downtown Omaha, Nebraska. A unique pollinator plant that really stands out in the bed, this native medicinal plant is a great addition to any herb garden. Historically, rattlesnake master has been used as a diuretic, diaphoretic (inducing sweating), expectorant, and, in large doses, an emetic (inducing vomiting) (King, 1905).

I first saw Eryngium yuccifolium Michx.—a.k.a rattlesnake master, button eryngo, or button snakeroot—planted at the Gene Leahy Mall, a park in downtown Omaha, Nebraska. A unique pollinator plant that really stands out in the bed, this native medicinal plant is a great addition to any herb garden. Historically, rattlesnake master has been used as a diuretic, diaphoretic (inducing sweating), expectorant, and, in large doses, an emetic (inducing vomiting) (King, 1905). The common name, “rattlesnake master,” was first recorded in John Adair’s book, (1775). This common name is also found in ethnobotanical accounts from the Muscogee (formerly called the Creek), Cherokee, Meskwaki, and Natchez tribes. Though ethnobotanical accounts differ on usages for rattlesnake master among various tribes/nations, all state this plant can be used to treat rattlesnake bites (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977). Today, however, this is not recommended. Among the Muscogee, the roots are taken as an analgesic (pain reliever), antirheumatic, blood medicine, gastrointestinal aid, kidney aid, panacea (cure-all), sedative, and venereal aid (NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977), while the Meskwaki tribe have used it in ceremonial medicine, as an antidote for poisons, and for treating bladder issues (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003).

The common name, “rattlesnake master,” was first recorded in John Adair’s book, (1775). This common name is also found in ethnobotanical accounts from the Muscogee (formerly called the Creek), Cherokee, Meskwaki, and Natchez tribes. Though ethnobotanical accounts differ on usages for rattlesnake master among various tribes/nations, all state this plant can be used to treat rattlesnake bites (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977). Today, however, this is not recommended. Among the Muscogee, the roots are taken as an analgesic (pain reliever), antirheumatic, blood medicine, gastrointestinal aid, kidney aid, panacea (cure-all), sedative, and venereal aid (NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977), while the Meskwaki tribe have used it in ceremonial medicine, as an antidote for poisons, and for treating bladder issues (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003). Besides its historical medicinal use, archeologists also consider this multi-purpose plant one of several ancient fiber plants used by native peoples for thousands of years. Slippers, sandals, and moccasins made with rattlesnake master have been found in Kentucky and Missouri. In Salts Cave, Kentucky, researchers identified rattlesnake master leaves as the main fiber used to construct slippers, dated to 1500 BCE (Gordon & Keating, 2001). In Missouri, ornate, complexly woven shoes dating from 1,000 to 8,000 years old have been identified as made with rattlesnake master, including adult- and child-sized slip-ons, sandals, and moccasins (Pringle, 1998).

Besides its historical medicinal use, archeologists also consider this multi-purpose plant one of several ancient fiber plants used by native peoples for thousands of years. Slippers, sandals, and moccasins made with rattlesnake master have been found in Kentucky and Missouri. In Salts Cave, Kentucky, researchers identified rattlesnake master leaves as the main fiber used to construct slippers, dated to 1500 BCE (Gordon & Keating, 2001). In Missouri, ornate, complexly woven shoes dating from 1,000 to 8,000 years old have been identified as made with rattlesnake master, including adult- and child-sized slip-ons, sandals, and moccasins (Pringle, 1998). While rattlesnake master isn’t currently represented in the National Herb Garden (NHG), it’s in the same genus as E. planum. Also known as blue sea holly, E. planum can be found in the NHG’s Dioscorides theme bed, having been mentioned in his historical text from the 1st century A.D. I first encountered blue sea holly in my grandma’s perennial bed. Native to Central Asia and Europe, blue sea holly is a medicinal plant like its American cousin, but is used to treat inflammatory disorders and, reputedly, epilepsy. Though similar in appearance to rattlesnake master, the flowers differ in color.

While rattlesnake master isn’t currently represented in the National Herb Garden (NHG), it’s in the same genus as E. planum. Also known as blue sea holly, E. planum can be found in the NHG’s Dioscorides theme bed, having been mentioned in his historical text from the 1st century A.D. I first encountered blue sea holly in my grandma’s perennial bed. Native to Central Asia and Europe, blue sea holly is a medicinal plant like its American cousin, but is used to treat inflammatory disorders and, reputedly, epilepsy. Though similar in appearance to rattlesnake master, the flowers differ in color. Dill,

Dill,

Many European and Asian cultures used dill for its medicinal qualities. In fact, the word “dill” stems from the Norse word “dilla” which means to lull or soothe. Indeed, some of its oldest medicinal uses (for which it’s still used today) were to soothe stomach problems, aid insomnia, and increase lactation in breastfeeding women. Traditional and Ayurvedic medicines today recommend “gripe water,” an infusion of dill seed in water, as a sleep and digestive aid, especially for children. Dill is more commonly used in Europe and Asia as a medicine than in the US. There is ongoing research to verify the traditional medicinal applications of the herb. According to

Many European and Asian cultures used dill for its medicinal qualities. In fact, the word “dill” stems from the Norse word “dilla” which means to lull or soothe. Indeed, some of its oldest medicinal uses (for which it’s still used today) were to soothe stomach problems, aid insomnia, and increase lactation in breastfeeding women. Traditional and Ayurvedic medicines today recommend “gripe water,” an infusion of dill seed in water, as a sleep and digestive aid, especially for children. Dill is more commonly used in Europe and Asia as a medicine than in the US. There is ongoing research to verify the traditional medicinal applications of the herb. According to  Besides being used in the food industry to make dill pickles, dill also flavors some Aquavit liqueurs and is used to perfume cosmetics, detergents, mouthwashes, and soaps.

Besides being used in the food industry to make dill pickles, dill also flavors some Aquavit liqueurs and is used to perfume cosmetics, detergents, mouthwashes, and soaps. A few years ago, the National Herb Garden installed a display called “Beer Garden: Beer Like You’ve Never Seen It Before.” This seasonal planting highlighted many plants used in the entire beer-making industry, not just for the beer itself. One of the plants we included was Quercus suber, the cork oak. This fascinating evergreen tree, though widely used around the world, is rarely mentioned in the herb world. So, I decided it was time to pop open the story of this arboricultural workhorse.

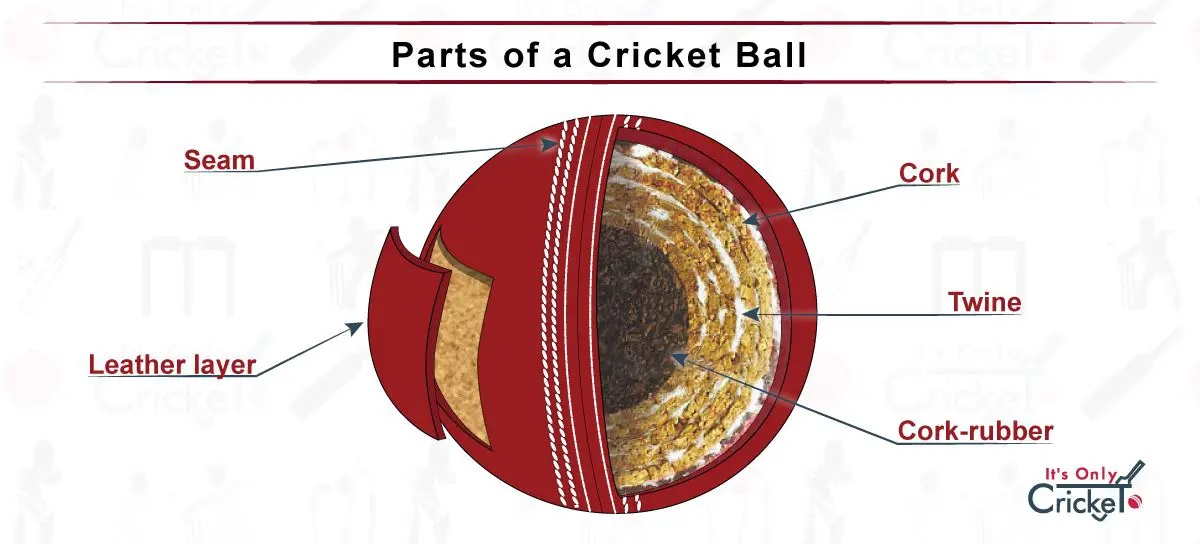

A few years ago, the National Herb Garden installed a display called “Beer Garden: Beer Like You’ve Never Seen It Before.” This seasonal planting highlighted many plants used in the entire beer-making industry, not just for the beer itself. One of the plants we included was Quercus suber, the cork oak. This fascinating evergreen tree, though widely used around the world, is rarely mentioned in the herb world. So, I decided it was time to pop open the story of this arboricultural workhorse. Cork oak is a western Mediterranean staple, not just because that’s its native range, but because it has become an important agricultural crop in countries like Spain and Portugal (Schery, 1972; Uphof, 1968). While in Spain a few years ago, I was enchanted by the thousands upon thousands of trees lined up like soldiers in fields alongside the road. Clearly, this tree was a big to-do in the area. Though none of the trees I saw reached more than 15 – 20 feet under cultivation, their wild relatives can reach 30 – 50 feet and live to be more than 200 years old. Unlike the easier-to-harvest crops like corn or wheat, cork harvesting doesn’t even begin until the trees reach 15 – 25 years old! So, a Quercus suber crop is, by all accounts, a long-term investment. (With improved cultivation techniques, this time frame could be shortened significantly, though it is less common.) Fortunately for the farmers, harvests occur about 12 – 13 times throughout the tree’s lifespan, about 200 years (Cork Institute of America, N.D.).

Cork oak is a western Mediterranean staple, not just because that’s its native range, but because it has become an important agricultural crop in countries like Spain and Portugal (Schery, 1972; Uphof, 1968). While in Spain a few years ago, I was enchanted by the thousands upon thousands of trees lined up like soldiers in fields alongside the road. Clearly, this tree was a big to-do in the area. Though none of the trees I saw reached more than 15 – 20 feet under cultivation, their wild relatives can reach 30 – 50 feet and live to be more than 200 years old. Unlike the easier-to-harvest crops like corn or wheat, cork harvesting doesn’t even begin until the trees reach 15 – 25 years old! So, a Quercus suber crop is, by all accounts, a long-term investment. (With improved cultivation techniques, this time frame could be shortened significantly, though it is less common.) Fortunately for the farmers, harvests occur about 12 – 13 times throughout the tree’s lifespan, about 200 years (Cork Institute of America, N.D.). Once removed, the bark is brought out of the fields and left out in the open to cure for approximately six months. According to the Cork Institute of America, “The cork bark is then sorted by quality and size. The first use is for the extraction of cork stoppers to meet the demands of the world’s wine and champagne industries, which use over 13 billion cork stoppers annually” – and for good reason. Cork is impermeable to liquids and gases. Though there has been a push to use other materials for bottle stoppers, including plastic versions (Schery, 1972), cork is by far the preferred—and more sustainable—material for this purpose. Cork forests are also hotbeds of biodiversity, giving shelter to many animal and plant species. Additionally, they capture atmospheric carbon and prevent erosion in drier, windswept areas (Sousa et al., 2009).

Once removed, the bark is brought out of the fields and left out in the open to cure for approximately six months. According to the Cork Institute of America, “The cork bark is then sorted by quality and size. The first use is for the extraction of cork stoppers to meet the demands of the world’s wine and champagne industries, which use over 13 billion cork stoppers annually” – and for good reason. Cork is impermeable to liquids and gases. Though there has been a push to use other materials for bottle stoppers, including plastic versions (Schery, 1972), cork is by far the preferred—and more sustainable—material for this purpose. Cork forests are also hotbeds of biodiversity, giving shelter to many animal and plant species. Additionally, they capture atmospheric carbon and prevent erosion in drier, windswept areas (Sousa et al., 2009). After the stoppers have been extracted, the leftover material is processed to create many new products, some familiar, while others are less well-known. For instance, cork is very heat resistant. Therefore, “the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) uses it to insulate the engines in rockets to protect them from high temperatures” (Birkenstock USA, 2024).

After the stoppers have been extracted, the leftover material is processed to create many new products, some familiar, while others are less well-known. For instance, cork is very heat resistant. Therefore, “the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) uses it to insulate the engines in rockets to protect them from high temperatures” (Birkenstock USA, 2024).

Aside from the cork itself, let’s not forget that Quercus suber trees also produce acorns. These acorns are a prime feed for Iberian pigs from which jamón ibérico (Iberian ham) is derived—a quintessential menu item in Spain and Portugal. Cork oaks are a typical component of dehesas

Aside from the cork itself, let’s not forget that Quercus suber trees also produce acorns. These acorns are a prime feed for Iberian pigs from which jamón ibérico (Iberian ham) is derived—a quintessential menu item in Spain and Portugal. Cork oaks are a typical component of dehesas , “a system oriented toward simultaneous and combined land use for Iberian pig, sheep, hunting, firewood, charcoal and occasionally cork. Because of this diversity of uses, the dehesa can be regarded as a mosaic, formed of different pieces with different uses and harvests: forest, labor and pasture (Cuevas et al., 1999)” (FSC, 2014).

, “a system oriented toward simultaneous and combined land use for Iberian pig, sheep, hunting, firewood, charcoal and occasionally cork. Because of this diversity of uses, the dehesa can be regarded as a mosaic, formed of different pieces with different uses and harvests: forest, labor and pasture (Cuevas et al., 1999)” (FSC, 2014).

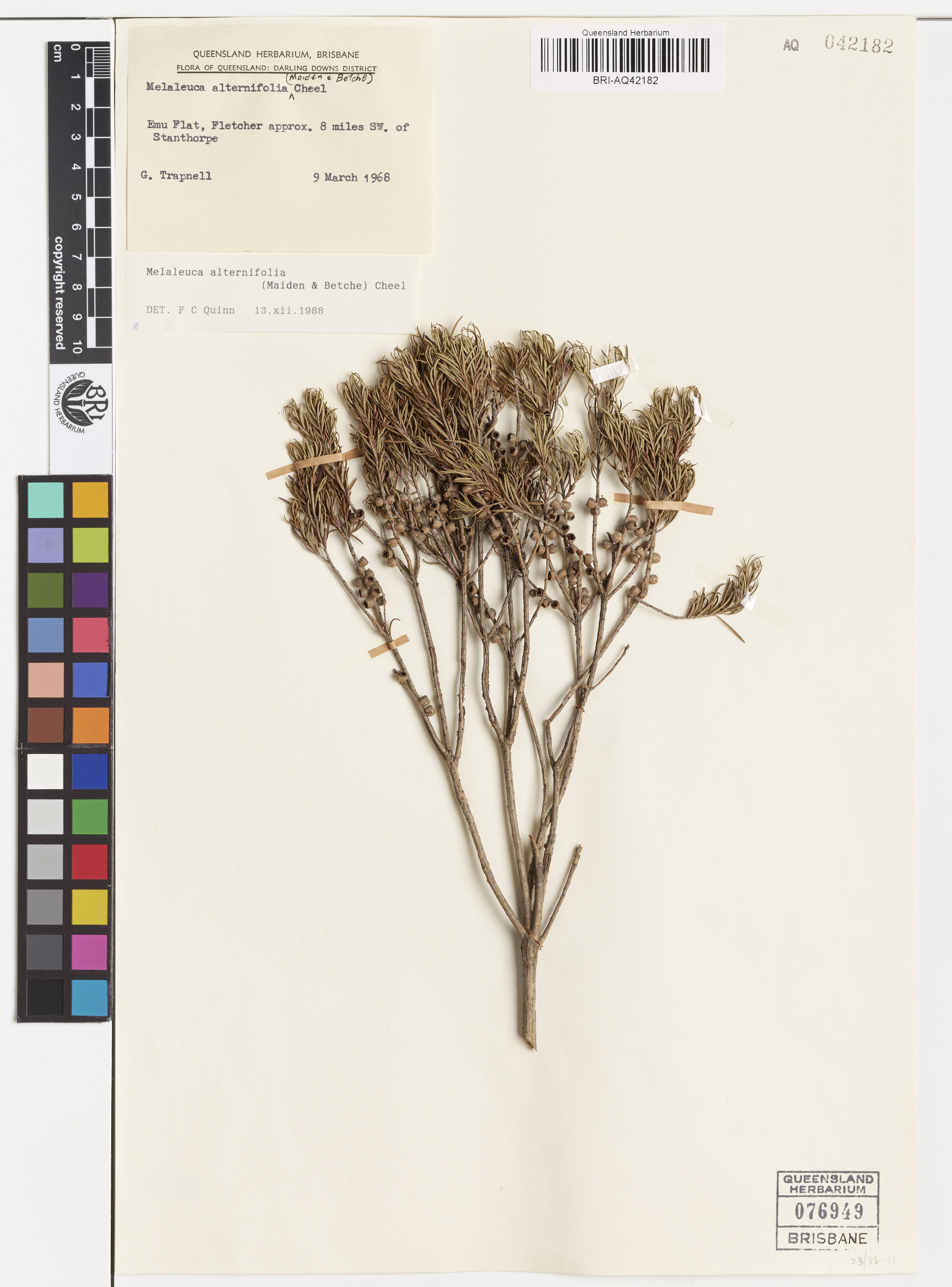

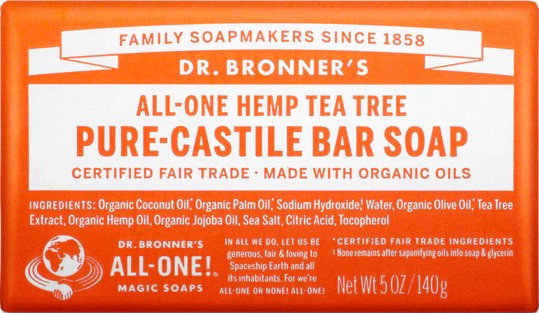

Many are familiar with the myriad of health benefits of using tea tree oil, but have you ever thought about how and why this Australian herb has ended up in small glass bottles on drug store shelves across the country? With benefits ranging from antifungal properties to aromatherapy, tea tree oil has become a staple of skincare, haircare, and naturopathic medicine in the 21

Many are familiar with the myriad of health benefits of using tea tree oil, but have you ever thought about how and why this Australian herb has ended up in small glass bottles on drug store shelves across the country? With benefits ranging from antifungal properties to aromatherapy, tea tree oil has become a staple of skincare, haircare, and naturopathic medicine in the 21 Long before first Europeans arrived in Botany Bay in 1788, the Bundjalung people of northern New South Wales utilized

Long before first Europeans arrived in Botany Bay in 1788, the Bundjalung people of northern New South Wales utilized  Demand for the antimicrobial and antifungal properties of tea tree oil really began to increase to substantial numbers in the 1970s, as part of a “general renaissance of interest in natural products” (

Demand for the antimicrobial and antifungal properties of tea tree oil really began to increase to substantial numbers in the 1970s, as part of a “general renaissance of interest in natural products” ( Since this increase in production and the commercialization of tea tree oil, countless uses for the essential oil have been found and shared amongst users and practitioners. The National Institutes of Health National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health reports that tea tree oil is promoted for use to combat “acne, athlete’s foot, lice, nail fungus, cuts, mite infection at the base of the eyelids, and insect bites” (NIH-NCCIH, 2020). The popularity of these uses is reflected in the wide range of tea tree oil-containing products available from many different producers. This popularity may also indicate the effectiveness of tea tree oil at combatting the microbes and fungi that are the main culprits in many of the aforementioned ailments. After all, if it wasn’t effective, would it have become as popular as it is today?

Since this increase in production and the commercialization of tea tree oil, countless uses for the essential oil have been found and shared amongst users and practitioners. The National Institutes of Health National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health reports that tea tree oil is promoted for use to combat “acne, athlete’s foot, lice, nail fungus, cuts, mite infection at the base of the eyelids, and insect bites” (NIH-NCCIH, 2020). The popularity of these uses is reflected in the wide range of tea tree oil-containing products available from many different producers. This popularity may also indicate the effectiveness of tea tree oil at combatting the microbes and fungi that are the main culprits in many of the aforementioned ailments. After all, if it wasn’t effective, would it have become as popular as it is today? Quality, regular sleep forms the foundation of our health and wellbeing, but what do you do if you’re trying to prioritize bedtime yet can’t get quality sleep? At least one third of Americans don’t get enough sleep – double that if you’re pregnant, postpartum, the parent of a young child or are going through perimenopause or surgical menopause. So many things can disrupt our sleep including blood sugar roller coasters, reproductive hormone fluctuations, stress, and sleep apnea. Many of these situations trigger a surge of cortisol or other stress hormone that wakes us up.

Quality, regular sleep forms the foundation of our health and wellbeing, but what do you do if you’re trying to prioritize bedtime yet can’t get quality sleep? At least one third of Americans don’t get enough sleep – double that if you’re pregnant, postpartum, the parent of a young child or are going through perimenopause or surgical menopause. So many things can disrupt our sleep including blood sugar roller coasters, reproductive hormone fluctuations, stress, and sleep apnea. Many of these situations trigger a surge of cortisol or other stress hormone that wakes us up. Sedatives

Sedatives Nervines

Nervines It depends widely on the herb and the individual. You might consider taking an adaptogen for daytime energy and stress response, which might set you up with better patterns to be able to relax at night. That said, some people find adaptogens to be

It depends widely on the herb and the individual. You might consider taking an adaptogen for daytime energy and stress response, which might set you up with better patterns to be able to relax at night. That said, some people find adaptogens to be  Maria Noël Groves, RH (AHG), clinical herbalist, runs Wintergreen Botanicals, nestled in the pine forests of New Hampshire. Her business is devoted to education and empowerment via classes, health consultations, and writing with the foundational belief that good health grows in nature. She is the author of the award-winning, best-selling

Maria Noël Groves, RH (AHG), clinical herbalist, runs Wintergreen Botanicals, nestled in the pine forests of New Hampshire. Her business is devoted to education and empowerment via classes, health consultations, and writing with the foundational belief that good health grows in nature. She is the author of the award-winning, best-selling  Cilantro (

Cilantro ( Cilantro originated in southwestern Asia and North Africa. Coriander, which is the seed

Cilantro originated in southwestern Asia and North Africa. Coriander, which is the seed  seeds would make one immortal. Arabs and Chinese both believed that it also stimulated sexual desire. It is mentioned in the Arabian classic,

seeds would make one immortal. Arabs and Chinese both believed that it also stimulated sexual desire. It is mentioned in the Arabian classic,  Thai cuisine relies heavily on cilantro leaves, seeds, and roots to flavor salads, soups,

Thai cuisine relies heavily on cilantro leaves, seeds, and roots to flavor salads, soups,  Cilantro is easily sown directly into the garden, but it does prefer cooler weather. After

Cilantro is easily sown directly into the garden, but it does prefer cooler weather. After