By Chrissy Moore

I fully admit to living under a rock. Many a friend and coworker has informed me of this character “trait.” Because I am not so worldly as others, I learn things by more circuitous routes. For example, my latest herbal discovery resulted from watching a recent episode of The Great British Baking Show. George, one of the bakers, remarked that he was including mastic in his bake. Of course, Paul Hollywood, one of the show’s hosts, commented with raised eyebrow, “A little mastic goes a long way.” George returned fire, stating, “You can never have too much mastic!” Clearly, mastic was near and dear to this Greek baker’s heart.

I fully admit to living under a rock. Many a friend and coworker has informed me of this character “trait.” Because I am not so worldly as others, I learn things by more circuitous routes. For example, my latest herbal discovery resulted from watching a recent episode of The Great British Baking Show. George, one of the bakers, remarked that he was including mastic in his bake. Of course, Paul Hollywood, one of the show’s hosts, commented with raised eyebrow, “A little mastic goes a long way.” George returned fire, stating, “You can never have too much mastic!” Clearly, mastic was near and dear to this Greek baker’s heart.

Unless you’re familiar with Greek cuisine or custom, as I am not, you may not have come across mastic–also known as Chios mastiha–in your comings and goings. But, if you are anything like me, you’d immediately start rooting around for information about this herbal ingredient, like a squirrel for a nut. I’ll save you some digging.

Mastic is a resin extracted from Pistacia lentiscus cv. Chia L. (Chios mastictree, mastic), which is a member of the Anacardiaceae family (GRIN-Global; Browicz, 1987). (Cashew, Anacardium occidentale L., and pistachio, Pistacia vera L., are also members of this family.) This small shrubby tree is native to numerous countries around the Mediterranean, from southern Europe to northern Africa to western Asia (Sturtevant, 1919), but it is most notably—and historically—linked to the Greek island of Chios in the northern Aegean Sea, about nine miles west (the way a crow flies) of the Turkish Çeşme peninsula.

Mastic is a resin extracted from Pistacia lentiscus cv. Chia L. (Chios mastictree, mastic), which is a member of the Anacardiaceae family (GRIN-Global; Browicz, 1987). (Cashew, Anacardium occidentale L., and pistachio, Pistacia vera L., are also members of this family.) This small shrubby tree is native to numerous countries around the Mediterranean, from southern Europe to northern Africa to western Asia (Sturtevant, 1919), but it is most notably—and historically—linked to the Greek island of Chios in the northern Aegean Sea, about nine miles west (the way a crow flies) of the Turkish Çeşme peninsula.

Pistacia lentiscus overlooking Finikas, Syros

It’s so linked to this island, in fact, that the island is referred to as the “mastic island,” since it has been the world’s largest producer of mastic resin for many years (Groom, 1992). “The production of mastic currently amounts to 160—170 tons per annum and plays an important role in the economy of the island  constituting the main source of income for approximately twenty villages in the south of Chios” (Browicz, 1987). The trees reach their full height after 40 – 50 years, but harvesting reaches its full potential after 12 – 15 years (FAO, 2021). Similar to frankincense (Boswellia spp.) and myrrh (Commiphora spp.), the mastic harvester nicks the tree bark to produce “tears,” or droplets, of resin, which then harden and are scraped off. These hardened blobs of resin are gathered and taken for processing (masticlife.com).

constituting the main source of income for approximately twenty villages in the south of Chios” (Browicz, 1987). The trees reach their full height after 40 – 50 years, but harvesting reaches its full potential after 12 – 15 years (FAO, 2021). Similar to frankincense (Boswellia spp.) and myrrh (Commiphora spp.), the mastic harvester nicks the tree bark to produce “tears,” or droplets, of resin, which then harden and are scraped off. These hardened blobs of resin are gathered and taken for processing (masticlife.com).

The resin undergoes some in-house cleaning and processing before it is given to the cooperative, Chios Gum Mastic Grower’s Association (CGMGA), for grading. Afterward, the graded mastic gum is shipped to and processed by the Union of Mastic Producers, who grinds it into a powder (FAO, 2021). The powdered form can then be incorporated into various foodstuffs, medicinal products (Varro et al., 1988), or left whole for chewing. Mastic is considered an early form of chewing gum, particularly for freshening the breath (Schery, 1972; Simpson and Ogorzaly, 2001; Sturtevant, 1919; Tyler et al., 1988). Currently, the largest importer of Chios mastic is Saudi Arabia, where chewing gum companies have incorporated the tree resin into numerous candy and confectionery products, particularly those of the dietetic variety (Batook, 2021; FAO, 2021).

If you haven’t picked up on the etymological relationship by now, translated from the Greek, mastic means “to gnash the teeth,” or in modern parlance, to chew or masticate…an appropriate term for the gummy treasure. Spurred on by the mention of it on The Great British Baking Show, I was on the hunt for this chewy, new-to-me herb. Fortunately, we have a husband-and-wife team of volunteers in the National Herb Garden, who just happened to live in Greece for a number of years. What better resource than these two to probe for information—outside of knowing a native of Chios, of course.

If you haven’t picked up on the etymological relationship by now, translated from the Greek, mastic means “to gnash the teeth,” or in modern parlance, to chew or masticate…an appropriate term for the gummy treasure. Spurred on by the mention of it on The Great British Baking Show, I was on the hunt for this chewy, new-to-me herb. Fortunately, we have a husband-and-wife team of volunteers in the National Herb Garden, who just happened to live in Greece for a number of years. What better resource than these two to probe for information—outside of knowing a native of Chios, of course.

They confirmed that mastic was, indeed, a ubiquitous flavoring in parts of Greece, including its use in mastika, a sweet liquor flavored with the resin (something else I had never heard of before) and ouzo, another Greek spirit. They said that you can find mastic gum and Turkish delight-esque candies all over Chios (well, in Greece, generally, and also in surrounding areas), as well as in well-appointed Mediterranean markets, even in the United States. I asked them what it tastes like, and they both hemmed and hawed trying to find the right words to describe its unique flavor. I immediately assumed it would be “pine-y” or “camphor-y” or something of the sort, since it is a tree resin, after all, but they both still hemmed seeming to suggest that it wasn’t exactly that strong.

They confirmed that mastic was, indeed, a ubiquitous flavoring in parts of Greece, including its use in mastika, a sweet liquor flavored with the resin (something else I had never heard of before) and ouzo, another Greek spirit. They said that you can find mastic gum and Turkish delight-esque candies all over Chios (well, in Greece, generally, and also in surrounding areas), as well as in well-appointed Mediterranean markets, even in the United States. I asked them what it tastes like, and they both hemmed and hawed trying to find the right words to describe its unique flavor. I immediately assumed it would be “pine-y” or “camphor-y” or something of the sort, since it is a tree resin, after all, but they both still hemmed seeming to suggest that it wasn’t exactly that strong.

Well, what then? What does it taste like? The only remedy for this inquisition was for them to seek out a market near where they live outside of Washington, DC, that might carry some sort of mastic-containing products. And they delivered! The following week, I was handed not just mastic chewing gum, but also mastic jellied candy. The candy was passed around amongst our volunteer group, and those adventurous enough to try plucked out a confectioner’s sugar-covered cube and commenced to masticate.

They were right: not exactly pine-y, but not exactly anything else either. I moved the candy around in my mouth trying to find words to describe it. Yes, it certainly had resinous, “pine-y” kinds of notes, but it also had a bit of a flowery essence to it. It was certainly unlike what I was expecting. Not nearly as strong as I thought it would be, but also not without character.

They were right: not exactly pine-y, but not exactly anything else either. I moved the candy around in my mouth trying to find words to describe it. Yes, it certainly had resinous, “pine-y” kinds of notes, but it also had a bit of a flowery essence to it. It was certainly unlike what I was expecting. Not nearly as strong as I thought it would be, but also not without character.

Not being particularly chef-y (I’m more of the baking sort), I’ve been trying to imagine what it would taste like in cooked or baked goods. Given that mastic rides that pine-y line, a heavy-handed cook might well overdo it. (Paul Hollywood was not without legitimate concern.) It’s a bit like using rose or lavender in food preparations: too much, and it can veer dangerously close to soap territory. But, used in moderation, it could pair nicely with other herbs/flavors. If you try it, let me know how it turns out!

Speaking of other herbal uses, mastic is also found in perfumes, personal hygiene products, and medicines. The resin has been used for centuries as a component of incense, particularly for the production of “moscholivano, [which] is a solid essence that, when burned, releases a pleasant odour” (FAO, 2021) and as an ingredient in chrism, the anointing oil used in the Eastern Orthodox Church (and others). In The Perfume Book, Groom says, “In early times the gum was used in pomanders and the oil was used to absorb other plant fragrances in the process of enfleurage. In modern perfumery, the extracted oil is used as a fixative in various perfume compounds; it appears, for example, in ‘Fahrenheit’.” According to Verrill, the resin is used as “a fixative for honeysuckle, lavender, sweet pea, mimosa, and other perfumes” (1940).

Speaking of other herbal uses, mastic is also found in perfumes, personal hygiene products, and medicines. The resin has been used for centuries as a component of incense, particularly for the production of “moscholivano, [which] is a solid essence that, when burned, releases a pleasant odour” (FAO, 2021) and as an ingredient in chrism, the anointing oil used in the Eastern Orthodox Church (and others). In The Perfume Book, Groom says, “In early times the gum was used in pomanders and the oil was used to absorb other plant fragrances in the process of enfleurage. In modern perfumery, the extracted oil is used as a fixative in various perfume compounds; it appears, for example, in ‘Fahrenheit’.” According to Verrill, the resin is used as “a fixative for honeysuckle, lavender, sweet pea, mimosa, and other perfumes” (1940).

Medicinally, mastic has taken on a number of roles over the centuries. In early Greek history, mastic was considered a cure-all in traditional Greek medicine, “relieving the diverse gastrointestinal disorders, such as abdominal pain, dyspepsia, gastritis and peptic ulcer for more than 2.500 [sic] years. More precisely, Hippocrates, Dioscorides and Galenos, among other Ancient Greek physicians, cited its properties and recommended its use” (CGMGA, 2021). A lengthy paper published by the Chios Gum Mastic Grower’s Association states,

Toothpaste containing mastic

“Nowadays, it is used as a seasoning in Mediterranean cuisine, in the production of chewing gum, in perfumery, in dentistry, and for the relief of epigastric pain and protection against peptic ulcer. It is of vital importance to mention that solid scientific evidence is constantly being produced regarding the therapeutic activity of Chios Mastiha. Its gastro-intestinal, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, antimicrobial, and anticancer activity, as well as its beneficial effects in oral hygiene and in skin care are firmly documented…. Mastiha is considered now as a traditional medicine for both stomach disorders and skin/wounds [sic] inflammations” (2019). In the the Greek City Times’ December 2021, article, the authors note that studies of mastic’s wide-ranging health benefits are ongoing, merely echoing, perhaps, what thousands of Chios natives have known for centuries. (Some of us are a little slow on the uptake!)

If you thought this story was over…not so fast. Mastic has a few more tricks up its sleeve. Mastic is used as a component of dental fillings, in dentifrices, and mouthwashes, helping to knock down pesky bacteria in the mouth. It should also be noted that “thanks to its quality as a colour stabilizer, mastiha is used for the production of high-grade varnishes” (CGMGA), such as those used in oil painting (megilp), and as a protective coating on photographic negatives. Rosin, a by-product of gum mastic’s distillation process, is used in myriad industries as well.

If you thought this story was over…not so fast. Mastic has a few more tricks up its sleeve. Mastic is used as a component of dental fillings, in dentifrices, and mouthwashes, helping to knock down pesky bacteria in the mouth. It should also be noted that “thanks to its quality as a colour stabilizer, mastiha is used for the production of high-grade varnishes” (CGMGA), such as those used in oil painting (megilp), and as a protective coating on photographic negatives. Rosin, a by-product of gum mastic’s distillation process, is used in myriad industries as well.

To put an exclamation mark at the end of this herbal story, mastic is certainly not a one-trick pony. On the contrary, I think Paul Hollywood was wrong and George was right: “You can never have too much mastic!” Something to chew on.

Photo Credits: 1) Baker George Arisitidou from Great British Bake Off (radiotimes.com); 2) Nativity map of Pistacia lentiscus cv. Chia (Botanical Museum, Helsinki, Finland); 3) Pistacia lentiscus overlooking Finikas, Syros (John Winder); 4) Mastic harvesting preparation (masticlife.com); 5) Mastic resin “tears” (Creative Commons–Ailinaleixo) and mastic resin (Creative Commons–פארוק); 6) Pistacia lentiscus leaves and fruit (John Winder); 7) Bottles of mastika and ouzo (Public Domain); 8) Mastic candy and chewing gum (C. Moore); 9) Mastic jellied candy (C. Moore); 10) Fahrenheit perfume (Public Domain); 11) Mastic toothpaste (ANEMOS); 12) Megilp containing mastic (Public Domain).

References

Batook, Incorporated. 2021. http://www.batook.com/about/. Accessed 16 December 2021.

Browicz, Kazimierz. 1987. Pistacia lentiscus cv. Chia (Anacardiaceae) on Chios Island.

Plant systematics and evolution, Vol. 155, No. 1/4, pp. 189-195. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23673827. Accessed 16 December 2021.

The Chios Gum Mastic Grower’s Association (CGMGA). https://www.gummastic.gr/en#gkContent. Accessed 15 December 2021.

The Chios Gum Mastic Grower’s Association (CGMGA). 2019. Overview of the major scientific publications on the beneficial activity of Chios mastiha. https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=https://www.gummastic.gr//images/brochures/en/Scientific_References_2019_en.pdf. Accessed 15 December 2021.

Greek City Times. https://greekcitytimes.com/2021/12/10/mastic-tree-resin-is-one-of-greeces-most-valuable-products/. Accessed 15 December 2021.

The University of Arizona Arboretum. https://apps.cals.arizona.edu/arboretum/taxon.aspx?id=216. Accessed 17 November 2021.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Forest resource utilisation and management in the Mediterranean. https://www.fao.org/3/x5593e/x5593e03.htm. Accessed 15 December 2021.

GRIN-Global Database. https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxon/taxonomydetail?id=28647. Accessed 17 November 2021.

Groom, Nigel. 1992. The perfume handbook, p. 142. London: Chapman & Hall.

“Mastic: Cultivation and Processing.” masticlife.com. https://masticlife.com/pages/mastic-cultivation-harvest-production. Accessed 4 January 2022.

Schery, Robert W. 1972. Pectins, gums, resins, oleoresins, and similar exudates, p. 244. In: Plants for man. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Simpson, Beryl B., Molly C. Ogorzaly. 2001. Hydrogels, elastic latexes, and resins, p. 259. In: Economic botany: plants in our world, 3rd Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Sturtevant, Edward. 1919. Sturtevant’s notes on edible plants, p. 440. Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, State Printers.

Verrill, A. Hyatt. 1940. Perfumes and spices including an account of soaps and cosmetics, p. 259. Clinton, Mass.: L.C. Page and Company.

Tyler, Varro E., Lynn R. Brady, and James E. Robbers. 1988. Resins and resin combinations, p. 143. In: Pharmacognosy, 9th Edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lea & Febiger.

Uphof, J.C. Th. 1968. Dictionary of economic plants, 2nd edition. New York, NY: Lubrecht & Cramer Ltd.

Medicinal Disclaimer: It is the policy of The Herb Society of America, Inc. not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health use. This information is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an endorsement of any particular medical or health treatment. Please consult a health care provider before pursuing any herbal treatments.

Chrissy Moore is the curator of the National Herb Garden at the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington, D.C. She is a member of the Potomac Unit of The Herb Society of America and is an International Society of Arboriculture certified arborist.

Dill, Anethum graveolens, has been grown and used for thousands of years. Dill is a native of the Mediterranean area and is an important part of northern European cuisines. It is an annual herb that will reseed if it likes where it is growing, and is one of the first herbs to appear in the spring garden. The foliage, often referred to as “dillweed,” is a tasty addition to fish, chicken, eggs, cucumber, and potato dishes. The yellow flowers that form on top of 2-3 foot stems appear in clusters which then become the seeds. The seeds are ready to harvest when brown and are used in pickling, vinegars, breads, and crackers.

Dill, Anethum graveolens, has been grown and used for thousands of years. Dill is a native of the Mediterranean area and is an important part of northern European cuisines. It is an annual herb that will reseed if it likes where it is growing, and is one of the first herbs to appear in the spring garden. The foliage, often referred to as “dillweed,” is a tasty addition to fish, chicken, eggs, cucumber, and potato dishes. The yellow flowers that form on top of 2-3 foot stems appear in clusters which then become the seeds. The seeds are ready to harvest when brown and are used in pickling, vinegars, breads, and crackers.  Many European and Asian cultures used dill for its medicinal qualities. In fact, the word “dill” stems from the Norse word “dilla” which means to lull or soothe. Indeed, some of its oldest medicinal uses (for which it’s still used today) were to soothe stomach problems, aid insomnia, and increase lactation in breastfeeding women. Traditional and Ayurvedic medicines today recommend “gripe water,” an infusion of dill seed in water, as a sleep and digestive aid, especially for children. Dill is more commonly used in Europe and Asia as a medicine than in the US. There is ongoing research to verify the traditional medicinal applications of the herb. According to Nutrition Today, “recent clinical trials evaluated dill and its extracts for managing risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as in improving outcomes during labor and delivery.“ One author states: “Talk about a useful organism – dill has also been known to stop the growth of certain bacterium such as E. coli, and streptococcus (staph infection)!” (Krumke, 2012).

Many European and Asian cultures used dill for its medicinal qualities. In fact, the word “dill” stems from the Norse word “dilla” which means to lull or soothe. Indeed, some of its oldest medicinal uses (for which it’s still used today) were to soothe stomach problems, aid insomnia, and increase lactation in breastfeeding women. Traditional and Ayurvedic medicines today recommend “gripe water,” an infusion of dill seed in water, as a sleep and digestive aid, especially for children. Dill is more commonly used in Europe and Asia as a medicine than in the US. There is ongoing research to verify the traditional medicinal applications of the herb. According to Nutrition Today, “recent clinical trials evaluated dill and its extracts for managing risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as in improving outcomes during labor and delivery.“ One author states: “Talk about a useful organism – dill has also been known to stop the growth of certain bacterium such as E. coli, and streptococcus (staph infection)!” (Krumke, 2012).  Besides being used in the food industry to make dill pickles, dill also flavors some Aquavit liqueurs and is used to perfume cosmetics, detergents, mouthwashes, and soaps.

Besides being used in the food industry to make dill pickles, dill also flavors some Aquavit liqueurs and is used to perfume cosmetics, detergents, mouthwashes, and soaps.

German chamomile,

German chamomile,  Ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans used chamomile as a medicine. Greek physicians Hippocrates and Dioscorides, and Roman physician Galen wrote about the medicinal uses of the herb. They used it to treat digestive issues, fever, and pain. It was also used to treat skin conditions. The root word of the plant’s botanical name, “matricaria”, is from the word “matrix,” which in Latin means “womb.” It was given this name because chamomile was used to treat gynecological problems and sleep disorders related to premenstrual syndrome.

Ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans used chamomile as a medicine. Greek physicians Hippocrates and Dioscorides, and Roman physician Galen wrote about the medicinal uses of the herb. They used it to treat digestive issues, fever, and pain. It was also used to treat skin conditions. The root word of the plant’s botanical name, “matricaria”, is from the word “matrix,” which in Latin means “womb.” It was given this name because chamomile was used to treat gynecological problems and sleep disorders related to premenstrual syndrome.  During the Middle Ages, chamomile was a common remedy for sleeplessness, anxiety, and digestive problems. It was believed to have anti-inflammatory properties so was also used to heal wounds and reduce swelling. Chamomile, because of its pleasant scent, was also used as a strewing herb in medieval homes. The name chamomile comes from the Greek word meaning “earth apple”, referring to the apple scent of the plant. By the 16

During the Middle Ages, chamomile was a common remedy for sleeplessness, anxiety, and digestive problems. It was believed to have anti-inflammatory properties so was also used to heal wounds and reduce swelling. Chamomile, because of its pleasant scent, was also used as a strewing herb in medieval homes. The name chamomile comes from the Greek word meaning “earth apple”, referring to the apple scent of the plant. By the 16 More than 120 chemical components have been identified in chamomile flowers, mostly in the essential oil. It’s interesting to note that the plant is sometimes called “blue chamomile” because of the blue color of its essential oil. The color is due to the azulene that is released during distillation (Mountain Rose, n.d.). Chamomile flowers contain pollen, so people who are sensitive to ragweed and chrysanthemum or other members of the Asteraceae family should be cautious about drinking chamomile tea (Kowalchik, 1998).

More than 120 chemical components have been identified in chamomile flowers, mostly in the essential oil. It’s interesting to note that the plant is sometimes called “blue chamomile” because of the blue color of its essential oil. The color is due to the azulene that is released during distillation (Mountain Rose, n.d.). Chamomile flowers contain pollen, so people who are sensitive to ragweed and chrysanthemum or other members of the Asteraceae family should be cautious about drinking chamomile tea (Kowalchik, 1998). German chamomile is an easy plant to grow. Seeds can be planted directly into the soil in the spring or fall. It is an annual, but it reseeds itself readily. It is a drought tolerant plant and if the soil is fertile, it will sport its flowers on thicker stalks. The plant can grow 2-3 feet tall and likes full sun or partial shade. The flowers should be harvested often or the plant cut back to encourage new growth and new flowers. Flowers are fragrant and can be used fresh or dried. The leaves of the plant are also edible. Roman chamomile

German chamomile is an easy plant to grow. Seeds can be planted directly into the soil in the spring or fall. It is an annual, but it reseeds itself readily. It is a drought tolerant plant and if the soil is fertile, it will sport its flowers on thicker stalks. The plant can grow 2-3 feet tall and likes full sun or partial shade. The flowers should be harvested often or the plant cut back to encourage new growth and new flowers. Flowers are fragrant and can be used fresh or dried. The leaves of the plant are also edible. Roman chamomile  Ginger,

Ginger,  Ginger is a very old spice. The Indians and the Chinese used ginger as a medicine over 5000 years ago to treat a variety of ailments (Bode, 2011). It was also used to flavor foods long before history was even recorded. The Greeks and the Romans introduced ginger to Europe and the Mediterranean area by way of the Arab traders. It became an important spice in Europe until the fall of the Roman Empire. When the Arabs re-established trade routes after the fall, ginger found its way back into European apothecaries and kitchens. It is said that one pound of ginger cost the same as one sheep in the 13th and 14

Ginger is a very old spice. The Indians and the Chinese used ginger as a medicine over 5000 years ago to treat a variety of ailments (Bode, 2011). It was also used to flavor foods long before history was even recorded. The Greeks and the Romans introduced ginger to Europe and the Mediterranean area by way of the Arab traders. It became an important spice in Europe until the fall of the Roman Empire. When the Arabs re-established trade routes after the fall, ginger found its way back into European apothecaries and kitchens. It is said that one pound of ginger cost the same as one sheep in the 13th and 14 Today, growing culinary ginger is not limited to the hot, humid areas of Southeast Asia and India as it was long ago. Anyone living in southern growing areas (USDA Hardiness Zones 8 – 12) can grow it as a perennial. In colder areas, it can be grown in pots and brought indoors for the winter or grown in the ground, but dug up before frost and potted up for overwintering indoors in a cool location. It prefers a rich, moist soil, good drainage, and shade in the south, but full sun in the north. If starting plants from store-bought ginger rhizomes, the rhizome should be first soaked in water to remove any growth retardant that may have been used. Each rhizome can be cut into sections with at least two eyes and planted in soil. Harvest the rhizomes when the leaves begin to fade.

Today, growing culinary ginger is not limited to the hot, humid areas of Southeast Asia and India as it was long ago. Anyone living in southern growing areas (USDA Hardiness Zones 8 – 12) can grow it as a perennial. In colder areas, it can be grown in pots and brought indoors for the winter or grown in the ground, but dug up before frost and potted up for overwintering indoors in a cool location. It prefers a rich, moist soil, good drainage, and shade in the south, but full sun in the north. If starting plants from store-bought ginger rhizomes, the rhizome should be first soaked in water to remove any growth retardant that may have been used. Each rhizome can be cut into sections with at least two eyes and planted in soil. Harvest the rhizomes when the leaves begin to fade.

using ginger in some form: fresh, ground, crystallized, pickled, preserved, or dried.

using ginger in some form: fresh, ground, crystallized, pickled, preserved, or dried.  Unfortunately for ginger, there is a dark side to its history.

Unfortunately for ginger, there is a dark side to its history.

While doing research for a presentation on herbal uses of native plants, I decided to look more into a plant I’d learned about in herb school, sweet flag (

While doing research for a presentation on herbal uses of native plants, I decided to look more into a plant I’d learned about in herb school, sweet flag ( Abenaki:

Abenaki:  Both species are perennial, grow in zones 4 to 10, have 1’–3’ tall iris-like leaves, and can spread 1’–2’. They bloom April through June, and like full sun to part shade. The inflorescence is a green spadix with no spathe (a spathe is a hood-like structure, like the white part of a peace lily). Both

Both species are perennial, grow in zones 4 to 10, have 1’–3’ tall iris-like leaves, and can spread 1’–2’. They bloom April through June, and like full sun to part shade. The inflorescence is a green spadix with no spathe (a spathe is a hood-like structure, like the white part of a peace lily). Both

This chemical distinction is important, because β-asarone has demonstrated procarcinogenic tendencies (meaning it could metabolize into a cancer causing compound), and the FDA has banned the use of “calamus, calamus oil, or extract of oil in food,” although these studies used high levels of isolated β-asarone and not “suggested doses of the whole plant in terms of mg/kg of body weight” that an herbalist would recommend. However, since

This chemical distinction is important, because β-asarone has demonstrated procarcinogenic tendencies (meaning it could metabolize into a cancer causing compound), and the FDA has banned the use of “calamus, calamus oil, or extract of oil in food,” although these studies used high levels of isolated β-asarone and not “suggested doses of the whole plant in terms of mg/kg of body weight” that an herbalist would recommend. However, since  Colonists also used

Colonists also used  Caraway seed,

Caraway seed,  References to caraway are found in the Ebers Papyrus (1500 BCE) and in the writings of the Greek physician, Dioscorides (50-70 CE). Some trace its use back to the Stone Age because fossilized seeds have been found around lake dwellings from that period. The Romans used caraway and spread its use to other parts of their realm. It has been cultivated in Europe since the Middle Ages.

References to caraway are found in the Ebers Papyrus (1500 BCE) and in the writings of the Greek physician, Dioscorides (50-70 CE). Some trace its use back to the Stone Age because fossilized seeds have been found around lake dwellings from that period. The Romans used caraway and spread its use to other parts of their realm. It has been cultivated in Europe since the Middle Ages.  The culinary use of caraway is well known. Caraway is used to make the north African chile sauce, harissa. It is also used in the traditional British seed cake that is enjoyed with tea (Marchetti, 2013). Its anise-like flavor is very popular in German and Slavic cuisines. The seed is used to flavor breads such as Jewish rye bread, sausages, cabbage, and fruit and vegetable dishes as well as cheeses such as Havarti. The leaves are added to soups and salads. The seeds are also used to make alcoholic drinks such as aquavit, kϋmmel, and vodka. The seeds can be sugar coated and used as a breath freshener or a digestive aid. The essential oil is used in perfumes, ice cream, candy, soft drinks, and to flavor children’s medicine (Bown, 2001). Growing up in a Slavic household, caraway seed was a staple spice in my mom’s kitchen.

The culinary use of caraway is well known. Caraway is used to make the north African chile sauce, harissa. It is also used in the traditional British seed cake that is enjoyed with tea (Marchetti, 2013). Its anise-like flavor is very popular in German and Slavic cuisines. The seed is used to flavor breads such as Jewish rye bread, sausages, cabbage, and fruit and vegetable dishes as well as cheeses such as Havarti. The leaves are added to soups and salads. The seeds are also used to make alcoholic drinks such as aquavit, kϋmmel, and vodka. The seeds can be sugar coated and used as a breath freshener or a digestive aid. The essential oil is used in perfumes, ice cream, candy, soft drinks, and to flavor children’s medicine (Bown, 2001). Growing up in a Slavic household, caraway seed was a staple spice in my mom’s kitchen.  I grow fennel,

I grow fennel,  In the fall, I clip the seed heads and put them in a paper bag. I save some seeds for sowing next year and some for the kitchen. The seeds have medicinal qualities (the foliage does not) and are often served at the end of the meal in restaurants to help with digestion and to freshen the breath. Eating the seeds or making a tea from the seeds can relieve flatulence, bloating, gas, indigestion, cramps, and muscle spasms. Fennel seeds are also called “meeting seeds,” because when the Puritans had long church sermons, they chewed on the seeds to suppress hunger and fatigue.

In the fall, I clip the seed heads and put them in a paper bag. I save some seeds for sowing next year and some for the kitchen. The seeds have medicinal qualities (the foliage does not) and are often served at the end of the meal in restaurants to help with digestion and to freshen the breath. Eating the seeds or making a tea from the seeds can relieve flatulence, bloating, gas, indigestion, cramps, and muscle spasms. Fennel seeds are also called “meeting seeds,” because when the Puritans had long church sermons, they chewed on the seeds to suppress hunger and fatigue. In the kitchen, seed can be used whole or ground or toasted in a dry frying pan. They can be used as a spice for baking sweets, bread, and crackers, or in sausage or herbal vinegars and in pickling. The seeds have the same anise flavor but are so sweet, they taste like they are sugar-coated. For me, it is like eating small candies, especially tasty after drinking coffee.

In the kitchen, seed can be used whole or ground or toasted in a dry frying pan. They can be used as a spice for baking sweets, bread, and crackers, or in sausage or herbal vinegars and in pickling. The seeds have the same anise flavor but are so sweet, they taste like they are sugar-coated. For me, it is like eating small candies, especially tasty after drinking coffee.  Fennel is easy to grow from seed and should be sowed directly in the garden. The plants have a tap root and do not like to be transplanted. The plants prefer full sun but can tolerate some shade, and they need well-drained soil. Treat them like summer annuals and sow seeds every year.

Fennel is easy to grow from seed and should be sowed directly in the garden. The plants have a tap root and do not like to be transplanted. The plants prefer full sun but can tolerate some shade, and they need well-drained soil. Treat them like summer annuals and sow seeds every year.  Peggy Riccio is the owner of

Peggy Riccio is the owner of  I fully admit to living under a rock. Many a friend and coworker has informed me of this character “trait.” Because I am not so worldly as others, I learn things by more circuitous routes. For example, my latest herbal discovery resulted from watching a recent episode of The Great British Baking Show. George, one of the bakers, remarked that he was including mastic in his bake. Of course, Paul Hollywood, one of the show’s hosts, commented with raised eyebrow, “A little mastic goes a long way.” George returned fire, stating, “You can never have too much mastic!” Clearly, mastic was near and dear to this Greek baker’s heart.

I fully admit to living under a rock. Many a friend and coworker has informed me of this character “trait.” Because I am not so worldly as others, I learn things by more circuitous routes. For example, my latest herbal discovery resulted from watching a recent episode of The Great British Baking Show. George, one of the bakers, remarked that he was including mastic in his bake. Of course, Paul Hollywood, one of the show’s hosts, commented with raised eyebrow, “A little mastic goes a long way.” George returned fire, stating, “You can never have too much mastic!” Clearly, mastic was near and dear to this Greek baker’s heart. Mastic is a resin extracted from Pistacia lentiscus cv. Chia L. (Chios mastictree, mastic), which is a member of the Anacardiaceae family (GRIN-Global; Browicz, 1987). (Cashew, Anacardium occidentale L., and pistachio, Pistacia vera L., are also members of this family.) This small shrubby tree is native to numerous countries around the Mediterranean, from southern Europe to northern Africa to western Asia (Sturtevant, 1919), but it is most notably—and historically—linked to the Greek island of Chios in the northern Aegean Sea, about nine miles west (the way a crow flies) of the Turkish

Mastic is a resin extracted from Pistacia lentiscus cv. Chia L. (Chios mastictree, mastic), which is a member of the Anacardiaceae family (GRIN-Global; Browicz, 1987). (Cashew, Anacardium occidentale L., and pistachio, Pistacia vera L., are also members of this family.) This small shrubby tree is native to numerous countries around the Mediterranean, from southern Europe to northern Africa to western Asia (Sturtevant, 1919), but it is most notably—and historically—linked to the Greek island of Chios in the northern Aegean Sea, about nine miles west (the way a crow flies) of the Turkish

constituting the main source of income for approximately twenty villages in the south of Chios” (Browicz, 1987). The trees reach their full height after 40 – 50 years, but harvesting reaches its full potential after 12 – 15 years (FAO, 2021). Similar to frankincense (Boswellia spp.) and myrrh (Commiphora spp.), the mastic harvester nicks the tree bark to produce “tears,” or droplets, of resin, which then harden and are scraped off. These hardened blobs of resin are gathered and taken for processing (masticlife.com).

constituting the main source of income for approximately twenty villages in the south of Chios” (Browicz, 1987). The trees reach their full height after 40 – 50 years, but harvesting reaches its full potential after 12 – 15 years (FAO, 2021). Similar to frankincense (Boswellia spp.) and myrrh (Commiphora spp.), the mastic harvester nicks the tree bark to produce “tears,” or droplets, of resin, which then harden and are scraped off. These hardened blobs of resin are gathered and taken for processing (masticlife.com).

If you haven’t picked up on the etymological relationship by now, translated from the Greek, mastic means “to gnash the teeth,” or in modern parlance, to chew or masticate…an appropriate term for the gummy treasure. Spurred on by the mention of it on The Great British Baking Show, I was on the hunt for this chewy, new-to-me herb. Fortunately, we have a husband-and-wife team of volunteers in the National Herb Garden, who just happened to live in Greece for a number of years. What better resource than these two to probe for information—outside of knowing a native of Chios, of course.

If you haven’t picked up on the etymological relationship by now, translated from the Greek, mastic means “to gnash the teeth,” or in modern parlance, to chew or masticate…an appropriate term for the gummy treasure. Spurred on by the mention of it on The Great British Baking Show, I was on the hunt for this chewy, new-to-me herb. Fortunately, we have a husband-and-wife team of volunteers in the National Herb Garden, who just happened to live in Greece for a number of years. What better resource than these two to probe for information—outside of knowing a native of Chios, of course. They confirmed that mastic was, indeed, a ubiquitous flavoring in parts of Greece, including its use in mastika, a sweet liquor flavored with the resin (something else I had never heard of before) and ouzo, another Greek spirit. They said that you can find mastic gum and Turkish delight-esque candies all over Chios (well, in Greece, generally, and also in surrounding areas), as well as in well-appointed Mediterranean markets, even in the United States. I asked them what it tastes like, and they both hemmed and hawed trying to find the right words to describe its unique flavor. I immediately assumed it would be “pine-y” or “camphor-y” or something of the sort, since it is a tree resin, after all, but they both still hemmed seeming to suggest that it wasn’t exactly that strong.

They confirmed that mastic was, indeed, a ubiquitous flavoring in parts of Greece, including its use in mastika, a sweet liquor flavored with the resin (something else I had never heard of before) and ouzo, another Greek spirit. They said that you can find mastic gum and Turkish delight-esque candies all over Chios (well, in Greece, generally, and also in surrounding areas), as well as in well-appointed Mediterranean markets, even in the United States. I asked them what it tastes like, and they both hemmed and hawed trying to find the right words to describe its unique flavor. I immediately assumed it would be “pine-y” or “camphor-y” or something of the sort, since it is a tree resin, after all, but they both still hemmed seeming to suggest that it wasn’t exactly that strong.

They were right: not exactly pine-y, but not exactly anything else either. I moved the candy around in my mouth trying to find words to describe it. Yes, it certainly had resinous, “pine-y” kinds of notes, but it also had a bit of a flowery essence to it. It was certainly unlike what I was expecting. Not nearly as strong as I thought it would be, but also not without character.

They were right: not exactly pine-y, but not exactly anything else either. I moved the candy around in my mouth trying to find words to describe it. Yes, it certainly had resinous, “pine-y” kinds of notes, but it also had a bit of a flowery essence to it. It was certainly unlike what I was expecting. Not nearly as strong as I thought it would be, but also not without character. Speaking of other herbal uses, mastic is also found in perfumes, personal hygiene products, and medicines. The resin has been used for centuries as a component of incense, particularly for the production of “moscholivano, [which] is a solid essence that, when burned, releases a pleasant odour” (FAO, 2021) and as an ingredient in chrism, the anointing oil used in the Eastern Orthodox Church (and others). In The Perfume Book,

Speaking of other herbal uses, mastic is also found in perfumes, personal hygiene products, and medicines. The resin has been used for centuries as a component of incense, particularly for the production of “moscholivano, [which] is a solid essence that, when burned, releases a pleasant odour” (FAO, 2021) and as an ingredient in chrism, the anointing oil used in the Eastern Orthodox Church (and others). In The Perfume Book,

If you thought this story was over…not so fast. Mastic has a few more tricks up its sleeve. Mastic is used as a component of dental fillings, in dentifrices, and mouthwashes, helping to knock down pesky bacteria in the mouth. It should also be noted that “thanks to its quality as a colour stabilizer, mastiha is used for the production of high-grade varnishes” (CGMGA), such as those used in oil painting (megilp), and as a protective coating on photographic negatives. Rosin, a by-product of gum mastic’s distillation process, is used in myriad industries as well.

If you thought this story was over…not so fast. Mastic has a few more tricks up its sleeve. Mastic is used as a component of dental fillings, in dentifrices, and mouthwashes, helping to knock down pesky bacteria in the mouth. It should also be noted that “thanks to its quality as a colour stabilizer, mastiha is used for the production of high-grade varnishes” (CGMGA), such as those used in oil painting (megilp), and as a protective coating on photographic negatives. Rosin, a by-product of gum mastic’s distillation process, is used in myriad industries as well. Many people may be familiar with the distinctive aroma of valerian root; old socks, wet dog, and horse manure are just a few things to which the odor has been affectionately compared. In fact, the constituent responsible for the smell, valeric acid, is also one of the components that causes swine manure to smell so badly (Chi, Lin, & Leu, 2005). Despite its odiferous qualities, valerian has been used for its sedative effects for over 2000 years. Valerian root is taken to relieve anxiety, promote sleep, and relax gastrointestinal spasms (Braun & Cohen, 2006). Some research shows that another compound, valerenic acid, may mediate anxiety by binding to GABA receptors in the brain, although the exact medicinally active compounds haven’t yet been pinpointed (Benke et al., 2009). It’s possible that valeric acid also has a role to play, as multiple constituents acting together may account for these effects (Spinella, 2002).

Many people may be familiar with the distinctive aroma of valerian root; old socks, wet dog, and horse manure are just a few things to which the odor has been affectionately compared. In fact, the constituent responsible for the smell, valeric acid, is also one of the components that causes swine manure to smell so badly (Chi, Lin, & Leu, 2005). Despite its odiferous qualities, valerian has been used for its sedative effects for over 2000 years. Valerian root is taken to relieve anxiety, promote sleep, and relax gastrointestinal spasms (Braun & Cohen, 2006). Some research shows that another compound, valerenic acid, may mediate anxiety by binding to GABA receptors in the brain, although the exact medicinally active compounds haven’t yet been pinpointed (Benke et al., 2009). It’s possible that valeric acid also has a role to play, as multiple constituents acting together may account for these effects (Spinella, 2002). Glycosaminoglycans, the medicinally active polysaccharides found in marshmallow root, have an appropriate abbreviation: GAGs. Mixing the powdered root with water or preparing an infused tea results in a slimy, mucilaginous mess that can be difficult to choke down. But it’s this very sliminess that causes marshmallow to work so well at soothing irritated tissue. Marshmallow is used for coughs, as a urinary demulcent, and for irritated skin. The mucilage forms a bioadhesive layer that acts as a barrier, protecting the tissue and allowing it to heal (Deters et al., 2010). Extracts of the root have also demonstrated antibacterial properties (Lauk, Lo Bue, Milazzo, Rapisarda, & Blandino, 2003;

Glycosaminoglycans, the medicinally active polysaccharides found in marshmallow root, have an appropriate abbreviation: GAGs. Mixing the powdered root with water or preparing an infused tea results in a slimy, mucilaginous mess that can be difficult to choke down. But it’s this very sliminess that causes marshmallow to work so well at soothing irritated tissue. Marshmallow is used for coughs, as a urinary demulcent, and for irritated skin. The mucilage forms a bioadhesive layer that acts as a barrier, protecting the tissue and allowing it to heal (Deters et al., 2010). Extracts of the root have also demonstrated antibacterial properties (Lauk, Lo Bue, Milazzo, Rapisarda, & Blandino, 2003;  No pub or bar would be complete without a bottle of bitters, with Angostura® being among the more popular brands. Although the recipe for Angostura® Bitters is a well-guarded secret, gentian is listed on the label as an ingredient and is likely a major contributor to the bitter flavor. By itself, gentian is considered extremely bitter and has been used as a yardstick when rating the bitterness of other herbs (Olivier & van Wyk, 2013). Bitter compounds in general have been shown to stimulate the secretion of saliva and digestive juices by activating the vagus nerve (Bone, 2003). The active constituents in gentian, gentiopicroside and amarogentin, are no exception. These molecules account for gentian’s use in improving digestion, increasing appetite, and relieving flatulence (Braun & Cohen, 2006).

No pub or bar would be complete without a bottle of bitters, with Angostura® being among the more popular brands. Although the recipe for Angostura® Bitters is a well-guarded secret, gentian is listed on the label as an ingredient and is likely a major contributor to the bitter flavor. By itself, gentian is considered extremely bitter and has been used as a yardstick when rating the bitterness of other herbs (Olivier & van Wyk, 2013). Bitter compounds in general have been shown to stimulate the secretion of saliva and digestive juices by activating the vagus nerve (Bone, 2003). The active constituents in gentian, gentiopicroside and amarogentin, are no exception. These molecules account for gentian’s use in improving digestion, increasing appetite, and relieving flatulence (Braun & Cohen, 2006). What list of nasty herbs would be complete without pukeweed? This alternate common name for lobelia says it all. The emetic qualities of this plant were made (in)famous by Dr. Samuel Thomson in the 19

What list of nasty herbs would be complete without pukeweed? This alternate common name for lobelia says it all. The emetic qualities of this plant were made (in)famous by Dr. Samuel Thomson in the 19 Betel nut (pronounced bet′-al) palm trees (

Betel nut (pronounced bet′-al) palm trees ( jackfruit (

jackfruit ( used as a fertilizer.

used as a fertilizer. Despite this medical information, the belief is that eating paan helps digestion, especially after a heavy meal with meat. Some people put chewing tobacco in the paan for an extra kick. The saliva containing tobacco is not swallowed; it is spit out. (Note: Saliva causes a chemical reaction to take place between the betel leaf (

Despite this medical information, the belief is that eating paan helps digestion, especially after a heavy meal with meat. Some people put chewing tobacco in the paan for an extra kick. The saliva containing tobacco is not swallowed; it is spit out. (Note: Saliva causes a chemical reaction to take place between the betel leaf ( Betel nut is a sacred fruit for most Hindu religious ceremonies. It can substitute for deities or can be used as an offering. Some Hindu rituals are to be performed by a couple. In such cases, if the man doing the ritual is widowed, the betel nut can be used in place of the wife. Traditional wedding invitations are started by giving betel nut to the invitees. Paradoxically, betel nuts are also a symbol of a commitment for an evil deal between criminals.

Betel nut is a sacred fruit for most Hindu religious ceremonies. It can substitute for deities or can be used as an offering. Some Hindu rituals are to be performed by a couple. In such cases, if the man doing the ritual is widowed, the betel nut can be used in place of the wife. Traditional wedding invitations are started by giving betel nut to the invitees. Paradoxically, betel nuts are also a symbol of a commitment for an evil deal between criminals. is also an evergreen, long-lived landscape tree, reaching a height of 40 to 60 feet tall and a width of up to 25 feet wide. Its pinnate leaves close up at night. The branches droop to the ground, making it a graceful shade tree. A mature tree can produce up to 350-500 pounds of fruit each year. It is native to tropical Africa and is in the Fabaceae family.

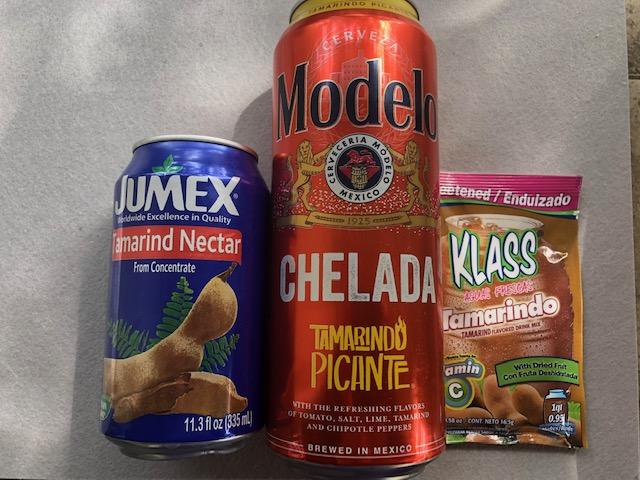

is also an evergreen, long-lived landscape tree, reaching a height of 40 to 60 feet tall and a width of up to 25 feet wide. Its pinnate leaves close up at night. The branches droop to the ground, making it a graceful shade tree. A mature tree can produce up to 350-500 pounds of fruit each year. It is native to tropical Africa and is in the Fabaceae family.  The tamarind tree grows well in USDA Hardiness Zones 10-11 and therefore, is not commonly seen in the continental United States, except in southern Florida. It produces a showy light brown, bean-like fruit, which can be left on the tree for up to six months after maturing. The sweet-sour pulp that surrounds the seeds is rich in calcium, phosphorus, iron, thiamine, and riboflavin and is a good source of niacin. The pulp is widely used in Mexico to make thirst-quenching juice drinks and even beer. It is also very popular in fruit candies. The fruit is used in Indian cuisines in curries, chutneys, meat sauces, and in a pickle dish called tamarind fish. Southeast Asians combine the pulp with chiles and use it for marinating chicken and fish before grilling. They also use it to flavor sauces, soups, and noodle dishes. Chefs in the United States are beginning to experiment with the sweet-sour flavor of tamarind pulp. Did you know that tamarind is a major ingredient in Lea & Perrins® Worcestershire Sauce?

The tamarind tree grows well in USDA Hardiness Zones 10-11 and therefore, is not commonly seen in the continental United States, except in southern Florida. It produces a showy light brown, bean-like fruit, which can be left on the tree for up to six months after maturing. The sweet-sour pulp that surrounds the seeds is rich in calcium, phosphorus, iron, thiamine, and riboflavin and is a good source of niacin. The pulp is widely used in Mexico to make thirst-quenching juice drinks and even beer. It is also very popular in fruit candies. The fruit is used in Indian cuisines in curries, chutneys, meat sauces, and in a pickle dish called tamarind fish. Southeast Asians combine the pulp with chiles and use it for marinating chicken and fish before grilling. They also use it to flavor sauces, soups, and noodle dishes. Chefs in the United States are beginning to experiment with the sweet-sour flavor of tamarind pulp. Did you know that tamarind is a major ingredient in Lea & Perrins® Worcestershire Sauce?  The fruit pods are long-lasting and can be found in some grocery stores, especially those serving Hispanic, Indian, and Southeast Asian populations.

The fruit pods are long-lasting and can be found in some grocery stores, especially those serving Hispanic, Indian, and Southeast Asian populations.  used as fodder for domestic animals and food for silkworms. The leaves are also used as garden mulch.

used as fodder for domestic animals and food for silkworms. The leaves are also used as garden mulch.  The fruit pulp is useful as a dye fixative, or combined with sea water, it cleans silver, brass, and copper. In addition to all of these uses, school children in Africa use the seeds as learning aids in arithmetic lessons and as counters in traditional board games.

The fruit pulp is useful as a dye fixative, or combined with sea water, it cleans silver, brass, and copper. In addition to all of these uses, school children in Africa use the seeds as learning aids in arithmetic lessons and as counters in traditional board games.