By Taylor Cammack

I first saw Eryngium yuccifolium Michx.—a.k.a rattlesnake master, button eryngo, or button snakeroot—planted at the Gene Leahy Mall, a park in downtown Omaha, Nebraska. A unique pollinator plant that really stands out in the bed, this native medicinal plant is a great addition to any herb garden. Historically, rattlesnake master has been used as a diuretic, diaphoretic (inducing sweating), expectorant, and, in large doses, an emetic (inducing vomiting) (King, 1905).

I first saw Eryngium yuccifolium Michx.—a.k.a rattlesnake master, button eryngo, or button snakeroot—planted at the Gene Leahy Mall, a park in downtown Omaha, Nebraska. A unique pollinator plant that really stands out in the bed, this native medicinal plant is a great addition to any herb garden. Historically, rattlesnake master has been used as a diuretic, diaphoretic (inducing sweating), expectorant, and, in large doses, an emetic (inducing vomiting) (King, 1905).

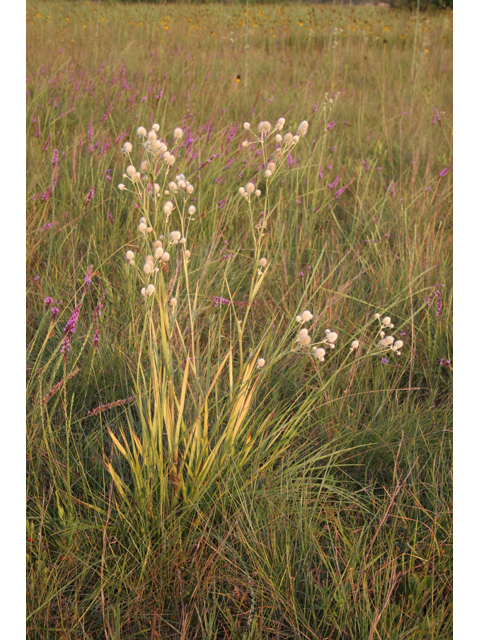

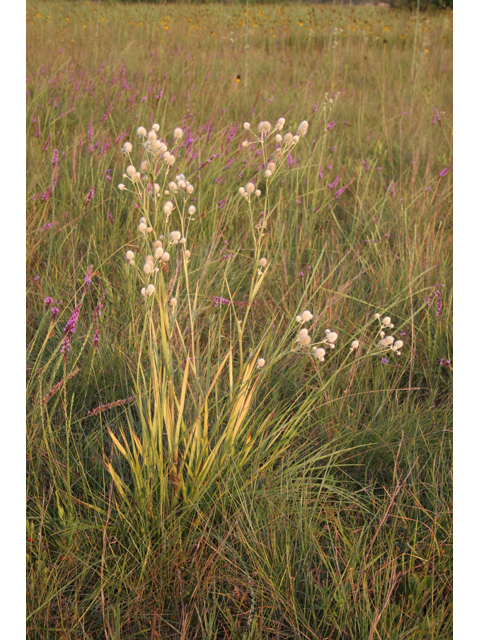

This perennial grows in midwestern prairies, savannas, swamps, and open woods across 23 states, from Florida to Maryland and Texas to Minnesota (Brakie, 2021). A warm-season, tap-rooted perennial, E. yuccifolium grows in medium to dry soils and loves full sun. Its bristly basal foliage resembles that of yucca (Yucca sp.)—hence the specific epithet—but rattlesnake master is in the Apiaceae family, the same as celery, carrot, and parsley. Each showy, whitish-green, round flower head is reminiscent of thistles and can last up to a month, blooming from June to September. Many pollinators love this plant, including black swallowtail butterflies, which use it as a larval host (Brakie, 2021). The seedheads persist until winter, giving multi-season interest in the garden, and the stems provide winter homes for insects (Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, 2024). In ideal growing conditions, it can self-seed—watch out for this and deadhead if you don’t want volunteers! The plants can be propagated by division and have few pest issues (Missouri Botanical Garden, 2024).

The common name, “rattlesnake master,” was first recorded in John Adair’s book, (1775). This common name is also found in ethnobotanical accounts from the Muscogee (formerly called the Creek), Cherokee, Meskwaki, and Natchez tribes. Though ethnobotanical accounts differ on usages for rattlesnake master among various tribes/nations, all state this plant can be used to treat rattlesnake bites (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977). Today, however, this is not recommended. Among the Muscogee, the roots are taken as an analgesic (pain reliever), antirheumatic, blood medicine, gastrointestinal aid, kidney aid, panacea (cure-all), sedative, and venereal aid (NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977), while the Meskwaki tribe have used it in ceremonial medicine, as an antidote for poisons, and for treating bladder issues (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003).

The common name, “rattlesnake master,” was first recorded in John Adair’s book, (1775). This common name is also found in ethnobotanical accounts from the Muscogee (formerly called the Creek), Cherokee, Meskwaki, and Natchez tribes. Though ethnobotanical accounts differ on usages for rattlesnake master among various tribes/nations, all state this plant can be used to treat rattlesnake bites (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977). Today, however, this is not recommended. Among the Muscogee, the roots are taken as an analgesic (pain reliever), antirheumatic, blood medicine, gastrointestinal aid, kidney aid, panacea (cure-all), sedative, and venereal aid (NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977), while the Meskwaki tribe have used it in ceremonial medicine, as an antidote for poisons, and for treating bladder issues (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003).

Besides its historical medicinal use, archeologists also consider this multi-purpose plant one of several ancient fiber plants used by native peoples for thousands of years. Slippers, sandals, and moccasins made with rattlesnake master have been found in Kentucky and Missouri. In Salts Cave, Kentucky, researchers identified rattlesnake master leaves as the main fiber used to construct slippers, dated to 1500 BCE (Gordon & Keating, 2001). In Missouri, ornate, complexly woven shoes dating from 1,000 to 8,000 years old have been identified as made with rattlesnake master, including adult- and child-sized slip-ons, sandals, and moccasins (Pringle, 1998).

Besides its historical medicinal use, archeologists also consider this multi-purpose plant one of several ancient fiber plants used by native peoples for thousands of years. Slippers, sandals, and moccasins made with rattlesnake master have been found in Kentucky and Missouri. In Salts Cave, Kentucky, researchers identified rattlesnake master leaves as the main fiber used to construct slippers, dated to 1500 BCE (Gordon & Keating, 2001). In Missouri, ornate, complexly woven shoes dating from 1,000 to 8,000 years old have been identified as made with rattlesnake master, including adult- and child-sized slip-ons, sandals, and moccasins (Pringle, 1998).

While rattlesnake master isn’t currently represented in the National Herb Garden (NHG), it’s in the same genus as E. planum. Also known as blue sea holly, E. planum can be found in the NHG’s Dioscorides theme bed, having been mentioned in his historical text from the 1st century A.D. I first encountered blue sea holly in my grandma’s perennial bed. Native to Central Asia and Europe, blue sea holly is a medicinal plant like its American cousin, but is used to treat inflammatory disorders and, reputedly, epilepsy. Though similar in appearance to rattlesnake master, the flowers differ in color.

While rattlesnake master isn’t currently represented in the National Herb Garden (NHG), it’s in the same genus as E. planum. Also known as blue sea holly, E. planum can be found in the NHG’s Dioscorides theme bed, having been mentioned in his historical text from the 1st century A.D. I first encountered blue sea holly in my grandma’s perennial bed. Native to Central Asia and Europe, blue sea holly is a medicinal plant like its American cousin, but is used to treat inflammatory disorders and, reputedly, epilepsy. Though similar in appearance to rattlesnake master, the flowers differ in color.

With its showy flowers, rattlesnake master can be a great native, pollinator-friendly alternative to its more commonly planted Eurasian relative. So, if you’re looking to mix up your herb garden, consider planting Eryngium yuccifolium this year!

Medicinal Disclaimer: It is the policy of The Herb Society of America, Inc. not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health use. This information is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an endorsement of any particular medical or health treatment. Please consult a healthcare provider before pursuing any herbal treatments.

Photo Credits: 1) Whole plant of rattlesnake master (Missouri Botanical Garden); 2) Rattlesnake master in its native habitat (Carolyn Fannon, Lawther Deer Park Prairie, Harris Co., Texas); 3) Ancient Indigenous sandal made from rattlesnake master (Museum of Anthropology-University of Missouri General Collection, item source, A. E. Henning); 4) Flower of rattlesnake master (Missouri Botanical Garden).

References

Adair, J.R. 1775. p. 238. The History of the American Indians. London: E. and C. Dilly. Accessed January 20, 2024. Available from: The history of the American Indians : Adair, James, approximately 1709-1783 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Brakie, M. 2021. Button eryngo (Eryngium yuccifolium) Plant Guide. USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service. Accessed January 16, 2024. Available from https://plants.sc.egov.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/plantguide/pdf/pg_eryu.pdf.

Gordon, A., and R.C. Keating. 2001. Light microscopy and determination of Eryngium yuccifolium Michx. leaf material in twined slippers from Salts Cave, Kentucky. Journal of Archaeological Science. 28, 1:55-60. Accessed January 16, 2024. Available from https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2000.0553.

Missouri Botanical Garden Plant Finder (Internet). 2024. Eryngium yuccifolium. Missouri Botanical Garden. Accessed January 22, 2024. Available from https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?kempercode=g500

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center Database (Internet). 2023. Eryngium yuccifolium (rattlesnake master). Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – The University of Texas at Austin. Accessed January 22, 2024. Available from https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=ERYU.

Kindscher, K. 1992. Medicinal wild plants of the prairie, pp. 99-102. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

King, J., H.W. Felter, and J.U. Lloyd. 1905. King’s American dispensatory, pp. 729-730. Cincinnati: Ohio Valley Co. 19th Ed. 3rd Rev. Vol. 1 Accessed February 9, 2024. Available from King’s American dispensatory by John King | Open Library.

Native American Ethnobotany Database (Internet). 2003. Eryngium yuccifolium. Accessed January 16, 2024. Available from http://naeb.brit.org/

Pringle, H. 1998. Eight Millennia of Footwear Fashion. Science Magazine. 281. 5373: 23+25. Accessed January 16, 2024. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2895363.

USDA, Agricultural Research Service, National Plant Germplasm System. 2024. Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN Taxonomy). National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland. Accessed 16 January 2024. Available from https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxon/taxonomydetail?id=102098.

Vogel, V. 1977. American Indian medicine, p. 371. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Taylor Cammack is a native of southeastern Nebraska where she grew up farming with her family. She received a degree in Plant and Landscape Systems from the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Taylor is the National Herb Garden intern for 2023-24. In her spare time, she enjoys reading, traveling, and baking (often unusual or quirky) recipes from old cookbooks.

With encouragement from the HSA Native Herb Conservation Committee and the GreenBridges™ project, our HSA Board of Directors joined more than 200 other national organizations and submitted a Resolution to the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives to recognize April 2024 as National Native Plant Month. This is the 4th year of this effort to promote America’s many beautiful and useful native plants.

With encouragement from the HSA Native Herb Conservation Committee and the GreenBridges™ project, our HSA Board of Directors joined more than 200 other national organizations and submitted a Resolution to the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives to recognize April 2024 as National Native Plant Month. This is the 4th year of this effort to promote America’s many beautiful and useful native plants. It occurred to some of us, under the influence of bright Spring colors, singing birds, and tantalizing warm breezes, that PICNICS would be a perfect way to celebrate our participation. Finding local natural areas in which to have a family and friends picnic would be a pleasant way to look a little closer at what we have for which we are grateful and even dependent. Looking a little closer, we soon learn that our native plants are equally dependent on us—for water, climate, pollinators, wildlife, and everything else that contributes to a healthy ecosystem and a happy family, whether plant or human.

It occurred to some of us, under the influence of bright Spring colors, singing birds, and tantalizing warm breezes, that PICNICS would be a perfect way to celebrate our participation. Finding local natural areas in which to have a family and friends picnic would be a pleasant way to look a little closer at what we have for which we are grateful and even dependent. Looking a little closer, we soon learn that our native plants are equally dependent on us—for water, climate, pollinators, wildlife, and everything else that contributes to a healthy ecosystem and a happy family, whether plant or human. Send a copy of your favorite picnic recipe to: HSA contact form. Send a photo of your picnic spot, too.

Send a copy of your favorite picnic recipe to: HSA contact form. Send a photo of your picnic spot, too.

People have had a relationship with herbs for thousands of years. They are consumed as food or flavoring and act as normalizers supporting natural health.

People have had a relationship with herbs for thousands of years. They are consumed as food or flavoring and act as normalizers supporting natural health.  Studies have found that bee balm contains many active constituents: the phenol, thymol, which protects the plant from microbial and fungal infections and does the same when consumed by people; the monoterpene linalool, which has an odor that attracts pollinating insects and acts as an antiseptic; and beta-phellandrene, which has antioxidant actions in plants, protecting them from UV radiation and in humans can act as an expectorant to relieve catarrh (mucus) and promote productive cough.

Studies have found that bee balm contains many active constituents: the phenol, thymol, which protects the plant from microbial and fungal infections and does the same when consumed by people; the monoterpene linalool, which has an odor that attracts pollinating insects and acts as an antiseptic; and beta-phellandrene, which has antioxidant actions in plants, protecting them from UV radiation and in humans can act as an expectorant to relieve catarrh (mucus) and promote productive cough. Harvest nettles wearing gloves.

Harvest nettles wearing gloves. I first saw Eryngium yuccifolium Michx.—a.k.a rattlesnake master, button eryngo, or button snakeroot—planted at the Gene Leahy Mall, a park in downtown Omaha, Nebraska. A unique pollinator plant that really stands out in the bed, this native medicinal plant is a great addition to any herb garden. Historically, rattlesnake master has been used as a diuretic, diaphoretic (inducing sweating), expectorant, and, in large doses, an emetic (inducing vomiting) (King, 1905).

I first saw Eryngium yuccifolium Michx.—a.k.a rattlesnake master, button eryngo, or button snakeroot—planted at the Gene Leahy Mall, a park in downtown Omaha, Nebraska. A unique pollinator plant that really stands out in the bed, this native medicinal plant is a great addition to any herb garden. Historically, rattlesnake master has been used as a diuretic, diaphoretic (inducing sweating), expectorant, and, in large doses, an emetic (inducing vomiting) (King, 1905). The common name, “rattlesnake master,” was first recorded in John Adair’s book, (1775). This common name is also found in ethnobotanical accounts from the Muscogee (formerly called the Creek), Cherokee, Meskwaki, and Natchez tribes. Though ethnobotanical accounts differ on usages for rattlesnake master among various tribes/nations, all state this plant can be used to treat rattlesnake bites (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977). Today, however, this is not recommended. Among the Muscogee, the roots are taken as an analgesic (pain reliever), antirheumatic, blood medicine, gastrointestinal aid, kidney aid, panacea (cure-all), sedative, and venereal aid (NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977), while the Meskwaki tribe have used it in ceremonial medicine, as an antidote for poisons, and for treating bladder issues (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003).

The common name, “rattlesnake master,” was first recorded in John Adair’s book, (1775). This common name is also found in ethnobotanical accounts from the Muscogee (formerly called the Creek), Cherokee, Meskwaki, and Natchez tribes. Though ethnobotanical accounts differ on usages for rattlesnake master among various tribes/nations, all state this plant can be used to treat rattlesnake bites (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977). Today, however, this is not recommended. Among the Muscogee, the roots are taken as an analgesic (pain reliever), antirheumatic, blood medicine, gastrointestinal aid, kidney aid, panacea (cure-all), sedative, and venereal aid (NAED, 2003; Vogel, 1977), while the Meskwaki tribe have used it in ceremonial medicine, as an antidote for poisons, and for treating bladder issues (Kindscher, 1992; NAED, 2003). Besides its historical medicinal use, archeologists also consider this multi-purpose plant one of several ancient fiber plants used by native peoples for thousands of years. Slippers, sandals, and moccasins made with rattlesnake master have been found in Kentucky and Missouri. In Salts Cave, Kentucky, researchers identified rattlesnake master leaves as the main fiber used to construct slippers, dated to 1500 BCE (Gordon & Keating, 2001). In Missouri, ornate, complexly woven shoes dating from 1,000 to 8,000 years old have been identified as made with rattlesnake master, including adult- and child-sized slip-ons, sandals, and moccasins (Pringle, 1998).

Besides its historical medicinal use, archeologists also consider this multi-purpose plant one of several ancient fiber plants used by native peoples for thousands of years. Slippers, sandals, and moccasins made with rattlesnake master have been found in Kentucky and Missouri. In Salts Cave, Kentucky, researchers identified rattlesnake master leaves as the main fiber used to construct slippers, dated to 1500 BCE (Gordon & Keating, 2001). In Missouri, ornate, complexly woven shoes dating from 1,000 to 8,000 years old have been identified as made with rattlesnake master, including adult- and child-sized slip-ons, sandals, and moccasins (Pringle, 1998). While rattlesnake master isn’t currently represented in the National Herb Garden (NHG), it’s in the same genus as E. planum. Also known as blue sea holly, E. planum can be found in the NHG’s Dioscorides theme bed, having been mentioned in his historical text from the 1st century A.D. I first encountered blue sea holly in my grandma’s perennial bed. Native to Central Asia and Europe, blue sea holly is a medicinal plant like its American cousin, but is used to treat inflammatory disorders and, reputedly, epilepsy. Though similar in appearance to rattlesnake master, the flowers differ in color.

While rattlesnake master isn’t currently represented in the National Herb Garden (NHG), it’s in the same genus as E. planum. Also known as blue sea holly, E. planum can be found in the NHG’s Dioscorides theme bed, having been mentioned in his historical text from the 1st century A.D. I first encountered blue sea holly in my grandma’s perennial bed. Native to Central Asia and Europe, blue sea holly is a medicinal plant like its American cousin, but is used to treat inflammatory disorders and, reputedly, epilepsy. Though similar in appearance to rattlesnake master, the flowers differ in color. Dill,

Dill,

Many European and Asian cultures used dill for its medicinal qualities. In fact, the word “dill” stems from the Norse word “dilla” which means to lull or soothe. Indeed, some of its oldest medicinal uses (for which it’s still used today) were to soothe stomach problems, aid insomnia, and increase lactation in breastfeeding women. Traditional and Ayurvedic medicines today recommend “gripe water,” an infusion of dill seed in water, as a sleep and digestive aid, especially for children. Dill is more commonly used in Europe and Asia as a medicine than in the US. There is ongoing research to verify the traditional medicinal applications of the herb. According to

Many European and Asian cultures used dill for its medicinal qualities. In fact, the word “dill” stems from the Norse word “dilla” which means to lull or soothe. Indeed, some of its oldest medicinal uses (for which it’s still used today) were to soothe stomach problems, aid insomnia, and increase lactation in breastfeeding women. Traditional and Ayurvedic medicines today recommend “gripe water,” an infusion of dill seed in water, as a sleep and digestive aid, especially for children. Dill is more commonly used in Europe and Asia as a medicine than in the US. There is ongoing research to verify the traditional medicinal applications of the herb. According to  Besides being used in the food industry to make dill pickles, dill also flavors some Aquavit liqueurs and is used to perfume cosmetics, detergents, mouthwashes, and soaps.

Besides being used in the food industry to make dill pickles, dill also flavors some Aquavit liqueurs and is used to perfume cosmetics, detergents, mouthwashes, and soaps. A few years ago, the National Herb Garden installed a display called “Beer Garden: Beer Like You’ve Never Seen It Before.” This seasonal planting highlighted many plants used in the entire beer-making industry, not just for the beer itself. One of the plants we included was Quercus suber, the cork oak. This fascinating evergreen tree, though widely used around the world, is rarely mentioned in the herb world. So, I decided it was time to pop open the story of this arboricultural workhorse.

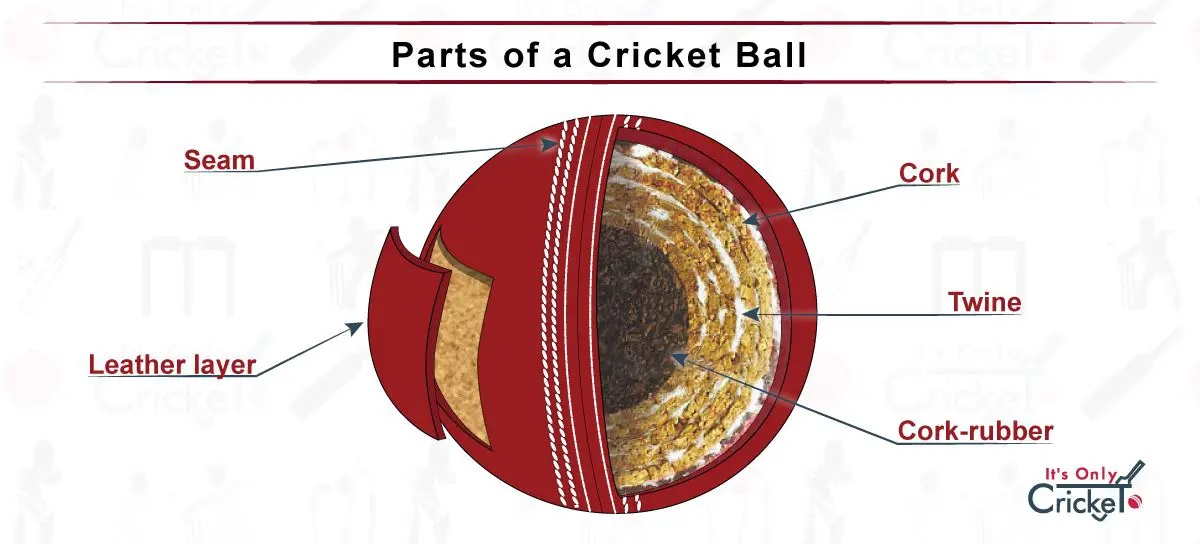

A few years ago, the National Herb Garden installed a display called “Beer Garden: Beer Like You’ve Never Seen It Before.” This seasonal planting highlighted many plants used in the entire beer-making industry, not just for the beer itself. One of the plants we included was Quercus suber, the cork oak. This fascinating evergreen tree, though widely used around the world, is rarely mentioned in the herb world. So, I decided it was time to pop open the story of this arboricultural workhorse. Cork oak is a western Mediterranean staple, not just because that’s its native range, but because it has become an important agricultural crop in countries like Spain and Portugal (Schery, 1972; Uphof, 1968). While in Spain a few years ago, I was enchanted by the thousands upon thousands of trees lined up like soldiers in fields alongside the road. Clearly, this tree was a big to-do in the area. Though none of the trees I saw reached more than 15 – 20 feet under cultivation, their wild relatives can reach 30 – 50 feet and live to be more than 200 years old. Unlike the easier-to-harvest crops like corn or wheat, cork harvesting doesn’t even begin until the trees reach 15 – 25 years old! So, a Quercus suber crop is, by all accounts, a long-term investment. (With improved cultivation techniques, this time frame could be shortened significantly, though it is less common.) Fortunately for the farmers, harvests occur about 12 – 13 times throughout the tree’s lifespan, about 200 years (Cork Institute of America, N.D.).

Cork oak is a western Mediterranean staple, not just because that’s its native range, but because it has become an important agricultural crop in countries like Spain and Portugal (Schery, 1972; Uphof, 1968). While in Spain a few years ago, I was enchanted by the thousands upon thousands of trees lined up like soldiers in fields alongside the road. Clearly, this tree was a big to-do in the area. Though none of the trees I saw reached more than 15 – 20 feet under cultivation, their wild relatives can reach 30 – 50 feet and live to be more than 200 years old. Unlike the easier-to-harvest crops like corn or wheat, cork harvesting doesn’t even begin until the trees reach 15 – 25 years old! So, a Quercus suber crop is, by all accounts, a long-term investment. (With improved cultivation techniques, this time frame could be shortened significantly, though it is less common.) Fortunately for the farmers, harvests occur about 12 – 13 times throughout the tree’s lifespan, about 200 years (Cork Institute of America, N.D.). Once removed, the bark is brought out of the fields and left out in the open to cure for approximately six months. According to the Cork Institute of America, “The cork bark is then sorted by quality and size. The first use is for the extraction of cork stoppers to meet the demands of the world’s wine and champagne industries, which use over 13 billion cork stoppers annually” – and for good reason. Cork is impermeable to liquids and gases. Though there has been a push to use other materials for bottle stoppers, including plastic versions (Schery, 1972), cork is by far the preferred—and more sustainable—material for this purpose. Cork forests are also hotbeds of biodiversity, giving shelter to many animal and plant species. Additionally, they capture atmospheric carbon and prevent erosion in drier, windswept areas (Sousa et al., 2009).

Once removed, the bark is brought out of the fields and left out in the open to cure for approximately six months. According to the Cork Institute of America, “The cork bark is then sorted by quality and size. The first use is for the extraction of cork stoppers to meet the demands of the world’s wine and champagne industries, which use over 13 billion cork stoppers annually” – and for good reason. Cork is impermeable to liquids and gases. Though there has been a push to use other materials for bottle stoppers, including plastic versions (Schery, 1972), cork is by far the preferred—and more sustainable—material for this purpose. Cork forests are also hotbeds of biodiversity, giving shelter to many animal and plant species. Additionally, they capture atmospheric carbon and prevent erosion in drier, windswept areas (Sousa et al., 2009). After the stoppers have been extracted, the leftover material is processed to create many new products, some familiar, while others are less well-known. For instance, cork is very heat resistant. Therefore, “the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) uses it to insulate the engines in rockets to protect them from high temperatures” (Birkenstock USA, 2024).

After the stoppers have been extracted, the leftover material is processed to create many new products, some familiar, while others are less well-known. For instance, cork is very heat resistant. Therefore, “the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) uses it to insulate the engines in rockets to protect them from high temperatures” (Birkenstock USA, 2024).

Aside from the cork itself, let’s not forget that Quercus suber trees also produce acorns. These acorns are a prime feed for Iberian pigs from which jamón ibérico (Iberian ham) is derived—a quintessential menu item in Spain and Portugal. Cork oaks are a typical component of dehesas

Aside from the cork itself, let’s not forget that Quercus suber trees also produce acorns. These acorns are a prime feed for Iberian pigs from which jamón ibérico (Iberian ham) is derived—a quintessential menu item in Spain and Portugal. Cork oaks are a typical component of dehesas , “a system oriented toward simultaneous and combined land use for Iberian pig, sheep, hunting, firewood, charcoal and occasionally cork. Because of this diversity of uses, the dehesa can be regarded as a mosaic, formed of different pieces with different uses and harvests: forest, labor and pasture (Cuevas et al., 1999)” (FSC, 2014).

, “a system oriented toward simultaneous and combined land use for Iberian pig, sheep, hunting, firewood, charcoal and occasionally cork. Because of this diversity of uses, the dehesa can be regarded as a mosaic, formed of different pieces with different uses and harvests: forest, labor and pasture (Cuevas et al., 1999)” (FSC, 2014).

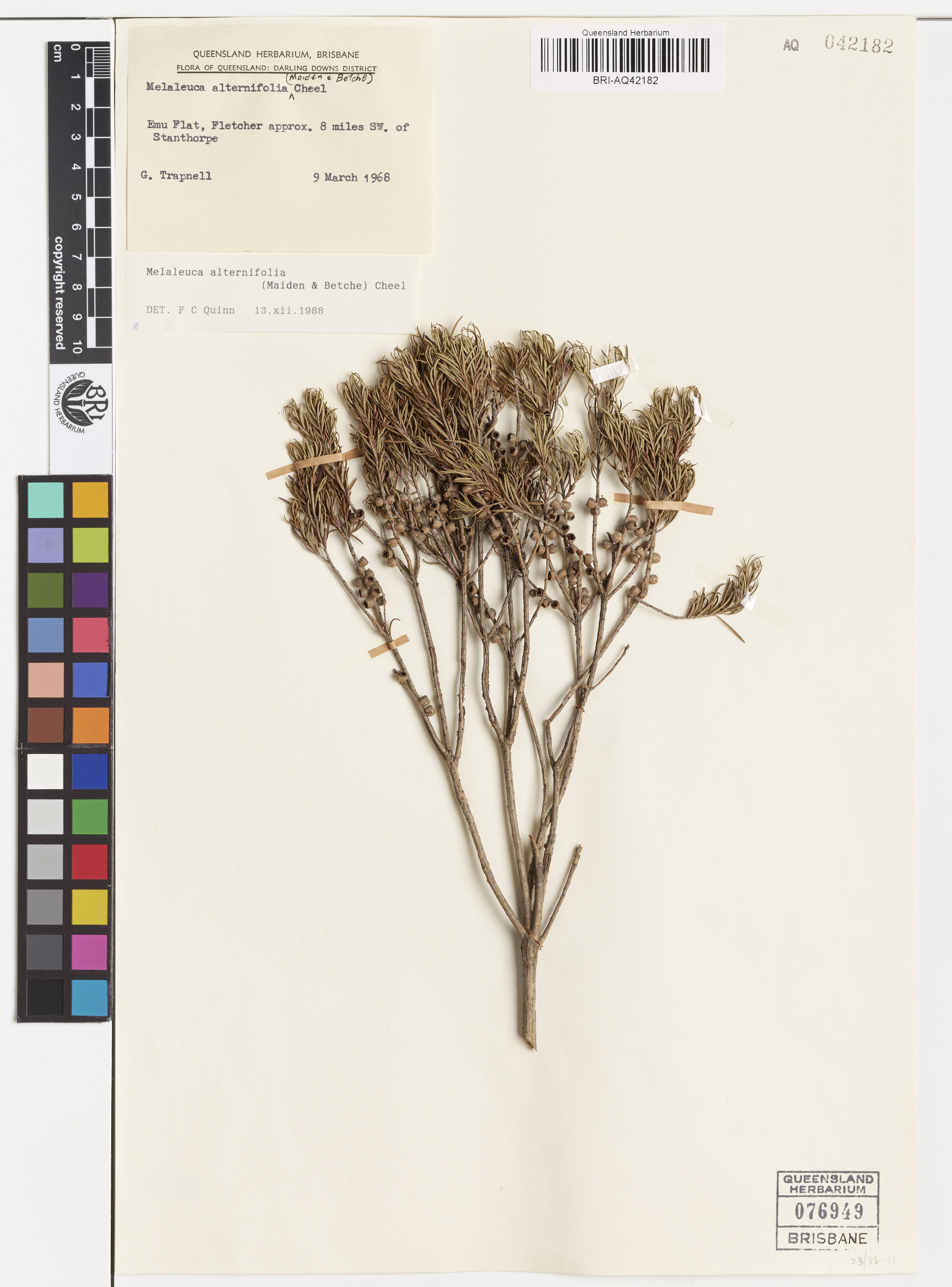

Many are familiar with the myriad of health benefits of using tea tree oil, but have you ever thought about how and why this Australian herb has ended up in small glass bottles on drug store shelves across the country? With benefits ranging from antifungal properties to aromatherapy, tea tree oil has become a staple of skincare, haircare, and naturopathic medicine in the 21

Many are familiar with the myriad of health benefits of using tea tree oil, but have you ever thought about how and why this Australian herb has ended up in small glass bottles on drug store shelves across the country? With benefits ranging from antifungal properties to aromatherapy, tea tree oil has become a staple of skincare, haircare, and naturopathic medicine in the 21 Long before first Europeans arrived in Botany Bay in 1788, the Bundjalung people of northern New South Wales utilized

Long before first Europeans arrived in Botany Bay in 1788, the Bundjalung people of northern New South Wales utilized  Demand for the antimicrobial and antifungal properties of tea tree oil really began to increase to substantial numbers in the 1970s, as part of a “general renaissance of interest in natural products” (

Demand for the antimicrobial and antifungal properties of tea tree oil really began to increase to substantial numbers in the 1970s, as part of a “general renaissance of interest in natural products” ( Since this increase in production and the commercialization of tea tree oil, countless uses for the essential oil have been found and shared amongst users and practitioners. The National Institutes of Health National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health reports that tea tree oil is promoted for use to combat “acne, athlete’s foot, lice, nail fungus, cuts, mite infection at the base of the eyelids, and insect bites” (NIH-NCCIH, 2020). The popularity of these uses is reflected in the wide range of tea tree oil-containing products available from many different producers. This popularity may also indicate the effectiveness of tea tree oil at combatting the microbes and fungi that are the main culprits in many of the aforementioned ailments. After all, if it wasn’t effective, would it have become as popular as it is today?

Since this increase in production and the commercialization of tea tree oil, countless uses for the essential oil have been found and shared amongst users and practitioners. The National Institutes of Health National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health reports that tea tree oil is promoted for use to combat “acne, athlete’s foot, lice, nail fungus, cuts, mite infection at the base of the eyelids, and insect bites” (NIH-NCCIH, 2020). The popularity of these uses is reflected in the wide range of tea tree oil-containing products available from many different producers. This popularity may also indicate the effectiveness of tea tree oil at combatting the microbes and fungi that are the main culprits in many of the aforementioned ailments. After all, if it wasn’t effective, would it have become as popular as it is today? Quality, regular sleep forms the foundation of our health and wellbeing, but what do you do if you’re trying to prioritize bedtime yet can’t get quality sleep? At least one third of Americans don’t get enough sleep – double that if you’re pregnant, postpartum, the parent of a young child or are going through perimenopause or surgical menopause. So many things can disrupt our sleep including blood sugar roller coasters, reproductive hormone fluctuations, stress, and sleep apnea. Many of these situations trigger a surge of cortisol or other stress hormone that wakes us up.

Quality, regular sleep forms the foundation of our health and wellbeing, but what do you do if you’re trying to prioritize bedtime yet can’t get quality sleep? At least one third of Americans don’t get enough sleep – double that if you’re pregnant, postpartum, the parent of a young child or are going through perimenopause or surgical menopause. So many things can disrupt our sleep including blood sugar roller coasters, reproductive hormone fluctuations, stress, and sleep apnea. Many of these situations trigger a surge of cortisol or other stress hormone that wakes us up. Sedatives

Sedatives Nervines

Nervines It depends widely on the herb and the individual. You might consider taking an adaptogen for daytime energy and stress response, which might set you up with better patterns to be able to relax at night. That said, some people find adaptogens to be

It depends widely on the herb and the individual. You might consider taking an adaptogen for daytime energy and stress response, which might set you up with better patterns to be able to relax at night. That said, some people find adaptogens to be  Maria Noël Groves, RH (AHG), clinical herbalist, runs Wintergreen Botanicals, nestled in the pine forests of New Hampshire. Her business is devoted to education and empowerment via classes, health consultations, and writing with the foundational belief that good health grows in nature. She is the author of the award-winning, best-selling

Maria Noël Groves, RH (AHG), clinical herbalist, runs Wintergreen Botanicals, nestled in the pine forests of New Hampshire. Her business is devoted to education and empowerment via classes, health consultations, and writing with the foundational belief that good health grows in nature. She is the author of the award-winning, best-selling  Cilantro (

Cilantro ( Cilantro originated in southwestern Asia and North Africa. Coriander, which is the seed

Cilantro originated in southwestern Asia and North Africa. Coriander, which is the seed  seeds would make one immortal. Arabs and Chinese both believed that it also stimulated sexual desire. It is mentioned in the Arabian classic,

seeds would make one immortal. Arabs and Chinese both believed that it also stimulated sexual desire. It is mentioned in the Arabian classic,  Thai cuisine relies heavily on cilantro leaves, seeds, and roots to flavor salads, soups,

Thai cuisine relies heavily on cilantro leaves, seeds, and roots to flavor salads, soups,  Cilantro is easily sown directly into the garden, but it does prefer cooler weather. After

Cilantro is easily sown directly into the garden, but it does prefer cooler weather. After

Onopordum acanthium is the Scotch thistle – a stately emblem of its country. It is reputedly eaten by donkeys (asses) and results in flatulence (farting). If you know of any other botanical Latin names that relate to sound, please let me know. I’d like to add more to this list. Could they possibly be any more intriguing than this one?

Onopordum acanthium is the Scotch thistle – a stately emblem of its country. It is reputedly eaten by donkeys (asses) and results in flatulence (farting). If you know of any other botanical Latin names that relate to sound, please let me know. I’d like to add more to this list. Could they possibly be any more intriguing than this one? In the heart of midwinter, when the world outside is hushed and still, a unique and enchanting rhythm emerges as we gently transition towards spring. It’s a time to draw our loved ones close, relish the warmth and comfort of home, and eagerly anticipate the bloom of a new season. Inspired by the indoor gardening adventures I’m sharing with my new grandson, I invite you to experience the essence of this magical season as we explore cozy traditions and heartwarming moments that make it truly special.

In the heart of midwinter, when the world outside is hushed and still, a unique and enchanting rhythm emerges as we gently transition towards spring. It’s a time to draw our loved ones close, relish the warmth and comfort of home, and eagerly anticipate the bloom of a new season. Inspired by the indoor gardening adventures I’m sharing with my new grandson, I invite you to experience the essence of this magical season as we explore cozy traditions and heartwarming moments that make it truly special. As herb enthusiasts, many of us delight in discussing the herbs that will find a home amidst the vegetables and flowers in our garden. The anticipation of planting basil, rosemary, lavender, and so many others always fills me with excitement. The best part? Not only do they add flavor to our meals, but herbs such as basil, rosemary, and lavender may also serve as essential allies in natural pest control.

As herb enthusiasts, many of us delight in discussing the herbs that will find a home amidst the vegetables and flowers in our garden. The anticipation of planting basil, rosemary, lavender, and so many others always fills me with excitement. The best part? Not only do they add flavor to our meals, but herbs such as basil, rosemary, and lavender may also serve as essential allies in natural pest control. As you adorn your home with nature’s beauty, consider adding a touch of herbal enchantment to your decor. Windowsills, sideboards, and kitchen tables can come alive with vibrant colors and fragrance of hyacinth, daffodil and narcissus bulbs, delicate snowdrops, and budding twigs that you’ve brought indoors to force. Embrace the opportunity to bring the outdoors in and lovingly place aromatic, healing herbs like mint and thyme in pots throughout your home.

As you adorn your home with nature’s beauty, consider adding a touch of herbal enchantment to your decor. Windowsills, sideboards, and kitchen tables can come alive with vibrant colors and fragrance of hyacinth, daffodil and narcissus bulbs, delicate snowdrops, and budding twigs that you’ve brought indoors to force. Embrace the opportunity to bring the outdoors in and lovingly place aromatic, healing herbs like mint and thyme in pots throughout your home.  Don’t forget to explore the world of herbal teas. As you cozy up by the hearth, sip on a cup of peppermint tea, known for its invigorating and digestive benefits. Peppermint’s refreshing flavor provides a delightful contrast to the richness of winter meals. Embrace the soothing properties of chamomile; its delicate, apple-like flavor is a soothing balm for the soul, making it the perfect companion for chilly winter evenings.

Don’t forget to explore the world of herbal teas. As you cozy up by the hearth, sip on a cup of peppermint tea, known for its invigorating and digestive benefits. Peppermint’s refreshing flavor provides a delightful contrast to the richness of winter meals. Embrace the soothing properties of chamomile; its delicate, apple-like flavor is a soothing balm for the soul, making it the perfect companion for chilly winter evenings. Medicinal Disclaimer:

Medicinal Disclaimer: