By Caroline Amidon and Joyce Brobst (Chrissy Moore, editor)

Editor’s Note: The majority of the information provided below was extracted from various presentations and handouts delivered by Caroline and Joyce over many years, with additions from the editor.

If you aren’t familiar with the Pelargonium plant, it’s one you definitely need to add to your garden repertoire! Scented geraniums, the other name by which these beauties are known, were discovered by Europeans in the early 1600s. They spread from the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to Europe, where their introduction brought about their association with herbs and herb gardens. In their native habitat, they are perennials and often grow into small shrubs.

If you aren’t familiar with the Pelargonium plant, it’s one you definitely need to add to your garden repertoire! Scented geraniums, the other name by which these beauties are known, were discovered by Europeans in the early 1600s. They spread from the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to Europe, where their introduction brought about their association with herbs and herb gardens. In their native habitat, they are perennials and often grow into small shrubs.

When introduced into France, Spain, Portugal, and England, they were sought after by wealthy collectors for cottage gardens. By 1790, approximately twenty varieties were being grown. Today, however, they are easily hybridized, and there are many varieties to choose from.

The French distilled their scented oils for the perfume industry, and they became commercially important. In North Africa, large fields were devoted to growing rose-scented types to supplement the “Attar of Rose” oils from the roses grown in Turkey. In recent years, the demand for essential oils has increased, and they are grown on Reunion Island, in Greece, Morocco, and China for this purpose.

The French distilled their scented oils for the perfume industry, and they became commercially important. In North Africa, large fields were devoted to growing rose-scented types to supplement the “Attar of Rose” oils from the roses grown in Turkey. In recent years, the demand for essential oils has increased, and they are grown on Reunion Island, in Greece, Morocco, and China for this purpose.

Aside from their scent, there is good reason for renewed interest in these adaptable and undemanding plants. They have diverse growth patterns, unusual textures, and foliage ranging in color from green to dusty gray to bright yellow. Most like full sun, mulching, and regular care but will survive with little water and partial shade.

Common leaf scents attributed to this group include: rose, citrus, fruit, mint, or spice. Popular varieties include Pelargonium graveolens (rose), P. crispum (lemon), P. odoratissimum (apple), P. tomentosum (peppermint), and P. ‘Nutmeg’.

Common leaf scents attributed to this group include: rose, citrus, fruit, mint, or spice. Popular varieties include Pelargonium graveolens (rose), P. crispum (lemon), P. odoratissimum (apple), P. tomentosum (peppermint), and P. ‘Nutmeg’.

We are frequently asked questions about scented geraniums’ personalities and habits, so we have provided some answers for those unfamiliar with this charming group of plants.

Do they bloom?

Yes, but not prolifically so. The name Pelargonium means “stork’s bill” and describes the scented geranium’s long, narrow seed capsule, which forms after flowering. The flowers are small and white, rose, lavender, or mauve in color with darker markings. Most flowers are unscented and sometimes sparse but may attract attention with their special elegance.

Are they poisonous?

No. The flowers, leaves, and extracts have been safely used for centuries; however, some are not desirable for flavoring. Also, because individuals can express allergic responses, normal precautions need to be taken when using them.

Can they be grown in containers?

They are excellent for container gardens. Because of the varied growth habits and versatility of this plant group, Pelargoniums can be selected for growing directly in the garden, in hanging pots, or in a container. Please note that plastic pots are convenient, but Pelargoniums do best in large clay pots and must be watered two or three times a week. It is best to research the growth habit of the type you are considering, since some types stay rather diminutive and will “drown” if planted in a pot that is too large; on the contrary, some varieties grow quite large by the end of the season and will need a larger pot to accommodate that growth so that they don’t dry out too quickly in between waterings.

They are excellent for container gardens. Because of the varied growth habits and versatility of this plant group, Pelargoniums can be selected for growing directly in the garden, in hanging pots, or in a container. Please note that plastic pots are convenient, but Pelargoniums do best in large clay pots and must be watered two or three times a week. It is best to research the growth habit of the type you are considering, since some types stay rather diminutive and will “drown” if planted in a pot that is too large; on the contrary, some varieties grow quite large by the end of the season and will need a larger pot to accommodate that growth so that they don’t dry out too quickly in between waterings.

What kind of care do they require?

If grown in a container, scented geraniums appreciate a well-drained potting mix (not topsoil). It is advisable to feed them regularly with a balanced liquid fertilizer, especially as certain varieties/cultivars can grow quite vigorously during the growing season and will need the added nutrition. If you are less “committed” to a regular liquid feed regimen, mixing in a slow-release fertilizer with the potting mix at planting time will aid the plants’ nutritional needs in between liquid fertilizations. These plants tolerate heavy pruning quite well, so remove dead or unsightly leaves or trim back branches as needed with good pruning shears just above a node (location on the stem where leaves emerge). Most varieties also propagate easily from cuttings, which makes them a great plant for sharing with friends or multiplying for your own garden displays. This also makes them kid friendly if you’d like to show this technique to children in a science class or at home.

If grown in a container, scented geraniums appreciate a well-drained potting mix (not topsoil). It is advisable to feed them regularly with a balanced liquid fertilizer, especially as certain varieties/cultivars can grow quite vigorously during the growing season and will need the added nutrition. If you are less “committed” to a regular liquid feed regimen, mixing in a slow-release fertilizer with the potting mix at planting time will aid the plants’ nutritional needs in between liquid fertilizations. These plants tolerate heavy pruning quite well, so remove dead or unsightly leaves or trim back branches as needed with good pruning shears just above a node (location on the stem where leaves emerge). Most varieties also propagate easily from cuttings, which makes them a great plant for sharing with friends or multiplying for your own garden displays. This also makes them kid friendly if you’d like to show this technique to children in a science class or at home.

Are they beneficial in the garden?

Some gardeners say that beneficial insects, like praying mantids and lady-bird beetles, are attracted to them, but because they are grown primarily for their leaves, they are not considered a “pollinator-attracting” plant.

Some gardeners say that beneficial insects, like praying mantids and lady-bird beetles, are attracted to them, but because they are grown primarily for their leaves, they are not considered a “pollinator-attracting” plant.

What uses do they have?

The oils can be used for perfumes or personal hygiene products; the leaves are used to make rose geranium jelly or syrup for flavoring cakes or sugars; the dried leaves are excellent additions to potpourris, sachets, and sleep pillows; and the plants are wonderful in gardens designed for children or the visually impaired. The plants can be shaped into topiaries, standards, or even bonsai.

Where can I buy scented geraniums?

Where can I buy scented geraniums?

Most retail nurseries or big-box stores don’t carry these great plants, but they should! Occasionally, you’ll see a select few in their herb section. Therefore, the best places to locate them are at local herb growers or herb plant sales, or through specialty catalogs. Many Herb Society of America units around the country conduct such plant sales, and Pelargoniums are often in their inventory. Some examples* of scented geranium growers include, but are not limited to:

- Geraniaceae, California

- Richter’s Herbs, Canada

- Well Sweep Herb Farm, New Jersey

- Sandy Mush Herb Nursery, North Carolina

As you work with these plants, you will want to find more varieties to add to your garden. Many creative uses develop because of their wonderful scents, variety of textures and colors, and their rapid growth. They bring much pleasure and delight to any garden. As you plan your next growing season, we encourage you to add one or many scented geraniums to your garden. We guarantee you will be pleasantly surprised!

As you work with these plants, you will want to find more varieties to add to your garden. Many creative uses develop because of their wonderful scents, variety of textures and colors, and their rapid growth. They bring much pleasure and delight to any garden. As you plan your next growing season, we encourage you to add one or many scented geraniums to your garden. We guarantee you will be pleasantly surprised!

*The Herb Society of America (HSA) does not endorse individual businesses. But, if you are seeking additional information, HSA is a great resource for most herb-related inquiries.

Medicinal Disclaimer: It is the policy of The Herb Society of America, Inc. not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health use. This information is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an endorsement of any particular medical or health treatment. Please consult a health care provider before pursuing any herbal treatments.

Photo Credits: 1) Pelargonium ‘Ardwick Cinnamon’ (C. Moore); 2) Pelargonium ‘Attar of Roses’ (J. Adams); 3) Pelargonium ‘Orange Fiz’ (C. Moore); 4) Pelargonium ‘Staghorn Oak’ flowers and Pelargonium panduriforme seedheads (C. Moore); 5) Pelargonium x fragrans in a clay pot (C. Moore); 6) Pelargonium cv. in a mixed container (C. Moore); 7) Pelargonium denticulatum leaves (K. Codrington-White); 8 & 9) Pelargonium cv. in mixed garden bed planting (C. Moore).

Additional References

In the many years that we have been collecting and growing the scented geraniums, we have worked diligently to provide correct nomenclature (the official naming of something) for the species or cultivars we are growing, lecturing, or writing about. The references listed below have reliable nomenclature, which helps when locating a particular plant.

Books

Becker, Jim and Faye Brawner. 1996. Scented geraniums: Knowing, growing, and enjoying scented Pelargoniums. Interweave Press: Loveland, Colorado.

- This is a great book for someone just getting to know the scented Pelargoniums.

Brawner, Faye. 2003. Geraniums: The complete encyclopedia. Schiffer Publishing, Ltd.: Atglen, PA.

- An excellent book providing information on all types of geraniums with background history on the plants.

Crocker, Pat, Caroline Amidon, and Joyce Brobst. 2006. Scented geranium, Pelargonium, 2006 Herb of the Year. Riversong Studios, Ltd.: Ontario, Canada.

- A guide to the history of scented geraniums, commonly grown varieties, and recipes for their use.

Miller, Diana. 1996. Pelargoniums: A gardener’s guide to the species and their hybrids and cultivars. Timber Press, Inc.: Portland, Oregon.

- An excellent reference for the serious grower or collector.

van der Walt, J.J.A. and P.J. Vorster. Pelargoniums of South Africa. (3 Volumes, 1979, 1981, 1988). National Botanic Gardens: Kirstenbosch, South Africa.

- A phenomenal three-volume series for anyone interested in pelargoniums. The illustrations are from original watercolors, which show all the exact features (flowers, leaves, and growth habit) of each plant included. In addition, wonderful descriptions of where these plants thrive in their native habitat of Southern Africa are clearly stated for each plant. This series is generally available in research libraries.

Periodicals

Amidon, Caroline, and Joyce Brobst. 2001. “Fun with Pelargoniums.” The Herbarist. Issue 67. The Herb Society of America.

Amidon, Caroline, and Joyce Brobst. 2005. “Heaven scent, a world of fun with Pelargoniums.” Green Scene. Pennsylvania Horticultural Society.

Amidon, Caroline, and Joyce Brobst. 2005. “To grow Pelargoniums is to know them.” The Herbarist. Issue 71. The Herb Society of America.

Caroline Amidon (now deceased) was Past President of The Herb Society of America (1996 -1998). She was awarded the Helen de Conway Little Medal of Honor from The Herb Society of America (2002), as well as The Nancy Putnam Howard Award for Horticultural Excellence (2005). Caroline was an honorary member of both The Philadelphia Unit and the PA Heartland Unit of The Herb Society of America. Caroline held various offices in and served on many committees for the Philadelphia Unit of HSA, as well as participated in the HSA registered plant collections program (Pelargonium species) and authored or co-authored numerous articles and texts.

Joyce Brobst is a Past President of The Herb Society of America (1998-2000). She was awarded the Helen de Conway Little Medal of Honor (2006) and the Nancy Putnam Howard Award for Excellence in Horticulture (2011). Joyce, an honorary member of both the PA Heartland Unit and Philadelphia Unit, has held offices and served on committees for both units. She is a Founders Circle member and is GreenBridges Garden certified. She, along with Caroline, has participated in the HSA registered plant collections program (Pelargonium species) and has authored or co-authored numerous articles and texts over the years.

With encouragement from the HSA Native Herb Conservation Committee and the GreenBridges™ project, our HSA Board of Directors joined more than 200 other national organizations and submitted a Resolution to the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives to recognize April 2024 as National Native Plant Month. This is the 4th year of this effort to promote America’s many beautiful and useful native plants.

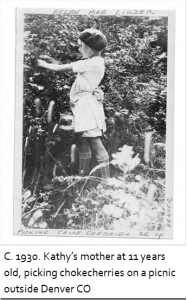

With encouragement from the HSA Native Herb Conservation Committee and the GreenBridges™ project, our HSA Board of Directors joined more than 200 other national organizations and submitted a Resolution to the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives to recognize April 2024 as National Native Plant Month. This is the 4th year of this effort to promote America’s many beautiful and useful native plants. It occurred to some of us, under the influence of bright Spring colors, singing birds, and tantalizing warm breezes, that PICNICS would be a perfect way to celebrate our participation. Finding local natural areas in which to have a family and friends picnic would be a pleasant way to look a little closer at what we have for which we are grateful and even dependent. Looking a little closer, we soon learn that our native plants are equally dependent on us—for water, climate, pollinators, wildlife, and everything else that contributes to a healthy ecosystem and a happy family, whether plant or human.

It occurred to some of us, under the influence of bright Spring colors, singing birds, and tantalizing warm breezes, that PICNICS would be a perfect way to celebrate our participation. Finding local natural areas in which to have a family and friends picnic would be a pleasant way to look a little closer at what we have for which we are grateful and even dependent. Looking a little closer, we soon learn that our native plants are equally dependent on us—for water, climate, pollinators, wildlife, and everything else that contributes to a healthy ecosystem and a happy family, whether plant or human. Send a copy of your favorite picnic recipe to: HSA contact form. Send a photo of your picnic spot, too.

Send a copy of your favorite picnic recipe to: HSA contact form. Send a photo of your picnic spot, too.

Cilantro (

Cilantro ( Cilantro originated in southwestern Asia and North Africa. Coriander, which is the seed

Cilantro originated in southwestern Asia and North Africa. Coriander, which is the seed  seeds would make one immortal. Arabs and Chinese both believed that it also stimulated sexual desire. It is mentioned in the Arabian classic,

seeds would make one immortal. Arabs and Chinese both believed that it also stimulated sexual desire. It is mentioned in the Arabian classic,  Thai cuisine relies heavily on cilantro leaves, seeds, and roots to flavor salads, soups,

Thai cuisine relies heavily on cilantro leaves, seeds, and roots to flavor salads, soups,  Cilantro is easily sown directly into the garden, but it does prefer cooler weather. After

Cilantro is easily sown directly into the garden, but it does prefer cooler weather. After  If you aren’t familiar with the Pelargonium plant, it’s one you definitely need to add to your garden repertoire! Scented geraniums, the other name by which these beauties are known, were discovered by Europeans in the early 1600s. They spread from the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to Europe, where their introduction brought about their association with herbs and herb gardens. In their native habitat, they are perennials and often grow into small shrubs.

If you aren’t familiar with the Pelargonium plant, it’s one you definitely need to add to your garden repertoire! Scented geraniums, the other name by which these beauties are known, were discovered by Europeans in the early 1600s. They spread from the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to Europe, where their introduction brought about their association with herbs and herb gardens. In their native habitat, they are perennials and often grow into small shrubs. The French distilled their scented oils for the perfume industry, and they became commercially important. In North Africa, large fields were devoted to growing rose-scented types to supplement the “Attar of Rose” oils from the roses grown in Turkey. In recent years, the demand for essential oils has increased, and they are grown on Reunion Island, in Greece, Morocco, and China for this purpose.

The French distilled their scented oils for the perfume industry, and they became commercially important. In North Africa, large fields were devoted to growing rose-scented types to supplement the “Attar of Rose” oils from the roses grown in Turkey. In recent years, the demand for essential oils has increased, and they are grown on Reunion Island, in Greece, Morocco, and China for this purpose. Common leaf scents attributed to this group include: rose, citrus, fruit, mint, or spice. Popular varieties include Pelargonium graveolens (rose), P. crispum (lemon), P. odoratissimum (apple), P. tomentosum (peppermint), and P. ‘Nutmeg’.

Common leaf scents attributed to this group include: rose, citrus, fruit, mint, or spice. Popular varieties include Pelargonium graveolens (rose), P. crispum (lemon), P. odoratissimum (apple), P. tomentosum (peppermint), and P. ‘Nutmeg’.

They are excellent for container gardens. Because of the varied growth habits and versatility of this plant group, Pelargoniums can be selected for growing directly in the garden, in hanging pots, or in a container. Please note that plastic pots are convenient, but Pelargoniums do best in large clay pots and must be watered two or three times a week. It is best to research the growth habit of the type you are considering, since some types stay rather diminutive and will “drown” if planted in a pot that is too large; on the contrary, some varieties grow quite large by the end of the season and will need a larger pot to accommodate that growth so that they don’t dry out too quickly in between waterings.

They are excellent for container gardens. Because of the varied growth habits and versatility of this plant group, Pelargoniums can be selected for growing directly in the garden, in hanging pots, or in a container. Please note that plastic pots are convenient, but Pelargoniums do best in large clay pots and must be watered two or three times a week. It is best to research the growth habit of the type you are considering, since some types stay rather diminutive and will “drown” if planted in a pot that is too large; on the contrary, some varieties grow quite large by the end of the season and will need a larger pot to accommodate that growth so that they don’t dry out too quickly in between waterings. If grown in a container, scented geraniums appreciate a well-drained potting mix (not topsoil). It is advisable to feed them regularly with a balanced liquid fertilizer, especially as certain varieties/cultivars can grow quite vigorously during the growing season and will need the added nutrition. If you are less “committed” to a regular liquid feed regimen, mixing in a slow-release fertilizer with the potting mix at planting time will aid the plants’ nutritional needs in between liquid fertilizations. These plants tolerate heavy pruning quite well, so remove dead or unsightly leaves or trim back branches as needed with good pruning shears just above a node (location on the stem where leaves emerge). Most varieties also propagate easily from cuttings, which makes them a great plant for sharing with friends or multiplying for your own garden displays. This also makes them kid friendly if you’d like to show this technique to children in a science class or at home.

If grown in a container, scented geraniums appreciate a well-drained potting mix (not topsoil). It is advisable to feed them regularly with a balanced liquid fertilizer, especially as certain varieties/cultivars can grow quite vigorously during the growing season and will need the added nutrition. If you are less “committed” to a regular liquid feed regimen, mixing in a slow-release fertilizer with the potting mix at planting time will aid the plants’ nutritional needs in between liquid fertilizations. These plants tolerate heavy pruning quite well, so remove dead or unsightly leaves or trim back branches as needed with good pruning shears just above a node (location on the stem where leaves emerge). Most varieties also propagate easily from cuttings, which makes them a great plant for sharing with friends or multiplying for your own garden displays. This also makes them kid friendly if you’d like to show this technique to children in a science class or at home. Some gardeners say that beneficial insects, like praying mantids and lady-bird beetles, are attracted to them, but because they are grown primarily for their leaves, they are not considered a “pollinator-attracting” plant.

Some gardeners say that beneficial insects, like praying mantids and lady-bird beetles, are attracted to them, but because they are grown primarily for their leaves, they are not considered a “pollinator-attracting” plant. Where can I buy scented geraniums?

Where can I buy scented geraniums? As you work with these plants, you will want to find more varieties to add to your garden. Many creative uses develop because of their wonderful scents, variety of textures and colors, and their rapid growth. They bring much pleasure and delight to any garden. As you plan your next growing season, we encourage you to add one or many scented geraniums to your garden. We guarantee you will be pleasantly surprised!

As you work with these plants, you will want to find more varieties to add to your garden. Many creative uses develop because of their wonderful scents, variety of textures and colors, and their rapid growth. They bring much pleasure and delight to any garden. As you plan your next growing season, we encourage you to add one or many scented geraniums to your garden. We guarantee you will be pleasantly surprised! Rosemary, The Herb Society’s Herb of the Month for November, is going through an identity crisis. Since the mid-18th century, the botanical name for rosemary has been Rosmarinus officinalis. However, after DNA research on the plant, scientists at the Royal Horticultural Society in London have decided that the characteristics of rosemary are more closely aligned with the Salvia genus and have, therefore, reclassified rosemary as Salvia rosmarinus. The common name will continue to be rosemary, however. John David, Head of the RHS Taxonomy Group, stated that “we cannot ignore what science is telling us, and clarity on a plant’s DNA helps us better understand its growth habits and cultural needs” (RHS, N.D.). Along with rosemary, Russian sage, Perovskia atriplicifolia, was also reclassified as a Salvia, as well as a few other garden plants.

Rosemary, The Herb Society’s Herb of the Month for November, is going through an identity crisis. Since the mid-18th century, the botanical name for rosemary has been Rosmarinus officinalis. However, after DNA research on the plant, scientists at the Royal Horticultural Society in London have decided that the characteristics of rosemary are more closely aligned with the Salvia genus and have, therefore, reclassified rosemary as Salvia rosmarinus. The common name will continue to be rosemary, however. John David, Head of the RHS Taxonomy Group, stated that “we cannot ignore what science is telling us, and clarity on a plant’s DNA helps us better understand its growth habits and cultural needs” (RHS, N.D.). Along with rosemary, Russian sage, Perovskia atriplicifolia, was also reclassified as a Salvia, as well as a few other garden plants. The first mention of rosemary was found on cuneiform tablets in 5000 BCE. Early Egyptians used it for embalming. Since Greek times, rosemary has been considered the “brain herb,” one that could increase memory and alertness. For that reason, Greek students wore crowns of rosemary when taking their exams. The historic Queen of Hungary Water, or Hungary Water, an infusion of rosemary in alcohol, was created by a monk to cure the headaches and joint pain of Queen Elizabeth of Hungary in the 14th century. The Queen claimed that it worked!

The first mention of rosemary was found on cuneiform tablets in 5000 BCE. Early Egyptians used it for embalming. Since Greek times, rosemary has been considered the “brain herb,” one that could increase memory and alertness. For that reason, Greek students wore crowns of rosemary when taking their exams. The historic Queen of Hungary Water, or Hungary Water, an infusion of rosemary in alcohol, was created by a monk to cure the headaches and joint pain of Queen Elizabeth of Hungary in the 14th century. The Queen claimed that it worked! Rosemary was, and still is, considered to be the herb of remembrance. Sprigs were placed in wedding bouquets as a symbol of fidelity. Historically, a sprig of rosemary was placed on a coffin or given to those attending a funeral (Brown, 2023). (Editor’s Note: For a reference to this practice in an important archaeological discovery at Historic St. Mary’s City, Maryland, see

Rosemary was, and still is, considered to be the herb of remembrance. Sprigs were placed in wedding bouquets as a symbol of fidelity. Historically, a sprig of rosemary was placed on a coffin or given to those attending a funeral (Brown, 2023). (Editor’s Note: For a reference to this practice in an important archaeological discovery at Historic St. Mary’s City, Maryland, see  Rosemary is native to the Mediterranean area, where it thrives in well-draining, sandy soil and plenty of sunshine. Its name means “dew of the sea,” recalling its native habitat. It is winter hardy in USDA Zones 8-10, although recent cold winters in Zone 8 make hardiness in that zone questionable with the exception of the ‘Arp’ cultivar, which can withstand lower temperatures. Rosemary is an evergreen plant with very fragrant, needle-like, gray-green leaves. It blooms December through April, although its blue-white flowers may appear throughout the summer as well. It is deer resistant. There are many varieties of rosemary, including a prostrate variety, which looks great cascading over a wall or in a container or hanging basket. Prostrate or upright rosemary can be grown in a container and overwintered inside in colder climates. However, the roots are susceptible to root rot if the soil does not drain well.

Rosemary is native to the Mediterranean area, where it thrives in well-draining, sandy soil and plenty of sunshine. Its name means “dew of the sea,” recalling its native habitat. It is winter hardy in USDA Zones 8-10, although recent cold winters in Zone 8 make hardiness in that zone questionable with the exception of the ‘Arp’ cultivar, which can withstand lower temperatures. Rosemary is an evergreen plant with very fragrant, needle-like, gray-green leaves. It blooms December through April, although its blue-white flowers may appear throughout the summer as well. It is deer resistant. There are many varieties of rosemary, including a prostrate variety, which looks great cascading over a wall or in a container or hanging basket. Prostrate or upright rosemary can be grown in a container and overwintered inside in colder climates. However, the roots are susceptible to root rot if the soil does not drain well. Rosemary is also a culinary herb that can be used fresh or dried. It accents the flavor of meats, fish, and vegetables, and is a great addition to stews, stuffing, vinegars, herbal salts, and butters. Its essential oil is used in perfumes, soaps, lotions, and shampoos, while the fragrant flowers and leaves are used in sachets and potpourris.

Rosemary is also a culinary herb that can be used fresh or dried. It accents the flavor of meats, fish, and vegetables, and is a great addition to stews, stuffing, vinegars, herbal salts, and butters. Its essential oil is used in perfumes, soaps, lotions, and shampoos, while the fragrant flowers and leaves are used in sachets and potpourris. Recently, I traveled to Wyoming’s capital city, Cheyenne, for a long-anticipated holiday. While there, I had the opportunity to visit the Cheyenne Botanic Gardens (CBG), which served as a jumping off point for my exploration of the area. The garden started as the Cheyenne Community Solar Greenhouse in the late 1970s, but a new, grant-funded botanic garden opened at its current location in 1984. The approximately nine-acre facility is clearly very forward-thinking in how it manages the local climatic conditions, including how it displays the myriad plants that can handle Cheyenne’s brutal growing conditions—conditions found in few other places outside of the Cheyenne vicinity. If you have not been to Cheyenne, or its surrounding plains and mountains, I highly recommend that you visit. The landscape has so many unique features, many of which don’t become apparent until you get up close and personal—my favorite way to view plants.

Recently, I traveled to Wyoming’s capital city, Cheyenne, for a long-anticipated holiday. While there, I had the opportunity to visit the Cheyenne Botanic Gardens (CBG), which served as a jumping off point for my exploration of the area. The garden started as the Cheyenne Community Solar Greenhouse in the late 1970s, but a new, grant-funded botanic garden opened at its current location in 1984. The approximately nine-acre facility is clearly very forward-thinking in how it manages the local climatic conditions, including how it displays the myriad plants that can handle Cheyenne’s brutal growing conditions—conditions found in few other places outside of the Cheyenne vicinity. If you have not been to Cheyenne, or its surrounding plains and mountains, I highly recommend that you visit. The landscape has so many unique features, many of which don’t become apparent until you get up close and personal—my favorite way to view plants. As you might imagine, one would hardly consider these ideal conditions for growing most herbs. Maybe some plants could handle one or two of these conditions, but all combined…not so much. I spoke with the CBG’s supervisory horticulturist, Isaiah Smith, himself an Alabama transplant, who told me many people offer such helpful “suggestions” as, “Why don’t you grow Southwest plants?” Smith says with a smirk, “Because the Southwest is dry and

As you might imagine, one would hardly consider these ideal conditions for growing most herbs. Maybe some plants could handle one or two of these conditions, but all combined…not so much. I spoke with the CBG’s supervisory horticulturist, Isaiah Smith, himself an Alabama transplant, who told me many people offer such helpful “suggestions” as, “Why don’t you grow Southwest plants?” Smith says with a smirk, “Because the Southwest is dry and  As I meandered through CBG’s herb garden and hiked in the natural areas outside of Cheyenne, I was trying to keep a sharp eye out for what herbs—either native or introduced—I might recognize and which seemed to be the best performers. The native species in the

As I meandered through CBG’s herb garden and hiked in the natural areas outside of Cheyenne, I was trying to keep a sharp eye out for what herbs—either native or introduced—I might recognize and which seemed to be the best performers. The native species in the  Artemisia tridentata

Artemisia tridentata Arctostaphylos uva-ursi

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi One of the most shocking herb-growing revelations was seeing the magnificent stand of French tarragon (

One of the most shocking herb-growing revelations was seeing the magnificent stand of French tarragon (

During this trip, my appreciation for those intrepid gardeners, professional or otherwise, who take on the challenge of places like Cheyenne—one of the most extreme environments in the country—went up exponentially. Whether you’re hiking through natural areas or strolling in the manicured gardens of a horticultural institution, successfully growing tough, weather-tested herbs in the high plains, no matter the genera, is a heroic effort few people are willing to embrace. Just ask Isaiah and his coworkers! In Cheyenne, though, and specifically at the Cheyenne Botanic Gardens where they showcase what is possible for all who visit, extreme conditions are all in a day’s work. My hat goes off (no pun intended) to all those high plains heroes whose capes we see whipping around in the prairie wind!

During this trip, my appreciation for those intrepid gardeners, professional or otherwise, who take on the challenge of places like Cheyenne—one of the most extreme environments in the country—went up exponentially. Whether you’re hiking through natural areas or strolling in the manicured gardens of a horticultural institution, successfully growing tough, weather-tested herbs in the high plains, no matter the genera, is a heroic effort few people are willing to embrace. Just ask Isaiah and his coworkers! In Cheyenne, though, and specifically at the Cheyenne Botanic Gardens where they showcase what is possible for all who visit, extreme conditions are all in a day’s work. My hat goes off (no pun intended) to all those high plains heroes whose capes we see whipping around in the prairie wind! The Aleppo pepper, also known as the Halaby pepper (Halab is the ancient name for the city Aleppo) has its origins in the city of Aleppo in northern Syria. Aleppo is one of the oldest cities in the world and was on the crossroads of the Silk Road 1,500 years ago. Unfortunately, the recent Syrian Civil War has left much of this ancient city in ruins. What the war did not destroy, the recent earthquake in February unfortunately added to its devastation.

The Aleppo pepper, also known as the Halaby pepper (Halab is the ancient name for the city Aleppo) has its origins in the city of Aleppo in northern Syria. Aleppo is one of the oldest cities in the world and was on the crossroads of the Silk Road 1,500 years ago. Unfortunately, the recent Syrian Civil War has left much of this ancient city in ruins. What the war did not destroy, the recent earthquake in February unfortunately added to its devastation.  One of the many results of the civil war in Syria was the disruption of trade of one of the area’s signature spices, the Aleppo pepper,

One of the many results of the civil war in Syria was the disruption of trade of one of the area’s signature spices, the Aleppo pepper,  The ground Aleppo pepper was, and is today, a highly sought after spice around the world. Unfortunately, the recent war was catastrophic for those who grew the pepper, and it became scarce. Some Syrian growers gathered seeds and moved to nearby Turkey to continue growing the plant. Turkish farmers also began growing the pepper; but, because of the different soil and environment, connoisseurs feel that the taste of the peppers grown in Turkey and other places is not as good as the peppers grown in Aleppo. Hopefully, the people of Aleppo will recover from the war and recent earthquake in order to begin growing their famous pepper plant again.

The ground Aleppo pepper was, and is today, a highly sought after spice around the world. Unfortunately, the recent war was catastrophic for those who grew the pepper, and it became scarce. Some Syrian growers gathered seeds and moved to nearby Turkey to continue growing the plant. Turkish farmers also began growing the pepper; but, because of the different soil and environment, connoisseurs feel that the taste of the peppers grown in Turkey and other places is not as good as the peppers grown in Aleppo. Hopefully, the people of Aleppo will recover from the war and recent earthquake in order to begin growing their famous pepper plant again. The Aleppo pepper is 10,000 Scoville Heat Units on the Scoville scale, twice as hot as the jalapeno pepper at 5,000 units, but less hot than the Serrano pepper at 23,000 units. The flavor is described as mildly hot and raisin-like with a hint of sun-dried tomatoes. It also has a slightly salty taste because after removing the seeds and drying the peppers, they are crushed with salt and olive oil and left to dry further. The heat of the pepper is not felt immediately as you eat it. The heat comes a bit later. Some say the taste is out of this world and leaves you begging for more. The pepper is a natural for grilled meats and kebabs, pasta, and chili. It is a key ingredient in muhammara, a Syrian roasted pepper dip.

The Aleppo pepper is 10,000 Scoville Heat Units on the Scoville scale, twice as hot as the jalapeno pepper at 5,000 units, but less hot than the Serrano pepper at 23,000 units. The flavor is described as mildly hot and raisin-like with a hint of sun-dried tomatoes. It also has a slightly salty taste because after removing the seeds and drying the peppers, they are crushed with salt and olive oil and left to dry further. The heat of the pepper is not felt immediately as you eat it. The heat comes a bit later. Some say the taste is out of this world and leaves you begging for more. The pepper is a natural for grilled meats and kebabs, pasta, and chili. It is a key ingredient in muhammara, a Syrian roasted pepper dip. Aleppo pepper may be difficult to find in a neighborhood grocery store. Middle Eastern markets will have it or it can be purchased online. I have found that its unique taste is worth the extra effort to find so that you can include it in your cooking.

Aleppo pepper may be difficult to find in a neighborhood grocery store. Middle Eastern markets will have it or it can be purchased online. I have found that its unique taste is worth the extra effort to find so that you can include it in your cooking. West Indian lemongrass, Cymbopogon citratus, is a fragrant member of the grass family (Poaceae). It has long, sharp-edged, narrow leaves and edible, small bulbous roots that resemble scallions. The plant is used as an ornamental grass in the garden, growing quite tall in a single season. It is evergreen in Zones 10 and 11, and the roots are winter hardy to Zones 8b, if protected. The foliage turns brown in the winter and should be trimmed back in the spring before new growth starts. It is an annual plant in zones lower than 8b.

West Indian lemongrass, Cymbopogon citratus, is a fragrant member of the grass family (Poaceae). It has long, sharp-edged, narrow leaves and edible, small bulbous roots that resemble scallions. The plant is used as an ornamental grass in the garden, growing quite tall in a single season. It is evergreen in Zones 10 and 11, and the roots are winter hardy to Zones 8b, if protected. The foliage turns brown in the winter and should be trimmed back in the spring before new growth starts. It is an annual plant in zones lower than 8b. Lemongrass can be grown from seed, or the crown and rhizome can be divided to create new plants. New plants can also be started from stalks purchased from a grocery store’s produce section. It rarely produces a flower when grown as an annual plant. It needs full sun, fertile soil, and adequate water and will grow easily in a container.

Lemongrass can be grown from seed, or the crown and rhizome can be divided to create new plants. New plants can also be started from stalks purchased from a grocery store’s produce section. It rarely produces a flower when grown as an annual plant. It needs full sun, fertile soil, and adequate water and will grow easily in a container. In India, the plant is used mostly for medicine. It is believed to have cooling properties and is sometimes called “fever grass.” It is used to treat stomachaches, digestive problems, and inflammation (Stephanie Lyon, N.D.). Lemongrass tea is thought to be antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant, and is also considered to be calming. Lemongrass is high in Vitamin A and is used in the “compounding of vitamins” (Madeline Hill, 1997). More research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of lemongrass on illness.

In India, the plant is used mostly for medicine. It is believed to have cooling properties and is sometimes called “fever grass.” It is used to treat stomachaches, digestive problems, and inflammation (Stephanie Lyon, N.D.). Lemongrass tea is thought to be antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant, and is also considered to be calming. Lemongrass is high in Vitamin A and is used in the “compounding of vitamins” (Madeline Hill, 1997). More research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of lemongrass on illness. The essential oil is also used by beekeepers to imitate a pheromone to attract bees to the hive or swarm (Hobbs, 2022).

The essential oil is also used by beekeepers to imitate a pheromone to attract bees to the hive or swarm (Hobbs, 2022). Tarragon,

Tarragon,  Today, tarragon is mostly used as a culinary herb; the mild licorice flavor is favored in French cuisine. It is called the “King of Herbs” in France, where it is used in many very popular dishes and sauces, particularly in Bearnaise sauce and Dijon mustard. It is one of the herbs in the French

Today, tarragon is mostly used as a culinary herb; the mild licorice flavor is favored in French cuisine. It is called the “King of Herbs” in France, where it is used in many very popular dishes and sauces, particularly in Bearnaise sauce and Dijon mustard. It is one of the herbs in the French  After the 2015 Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine was awarded for the discovery of the effective use of

After the 2015 Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine was awarded for the discovery of the effective use of  French tarragon is only one of the many, many

French tarragon is only one of the many, many

Recipe from the Healthy Hildegard website:

Recipe from the Healthy Hildegard website: Shanon Sterringer holds a PhD in Ethical and Creative Leadership (focused on the model of St. Hildegard of Bingen); a DMin, two master’s degrees (MA in theology and MA in ministry), and a BA in Medieval History. She is the founding pastor of the Hildegard Haus in Fairport Harbor, OH, and the owner of The Green Shepherdess Fair-Trade shop and local art studio, also in Fairport Harbor. She has traveled to the Rhine Valley several times since 2015 (most recently in January 2023) to walk in the footsteps of St. Hildegard. She has dedicated the last ten years of her life to studying Hildegard’s charism, most particularly as it relates to holistic health and spirituality. While on sabbatical in 2019, Shanon spent most of the year learning about herbs while working for a local herbalist, Lynn Abbey, at Blue Lake Botanicals in Willoughby, Ohio. Shanon is married and the mother of three adult daughters and has published two books on the topic of Hildegard (Forbidden Grace and 30 Day Journey with St. Hildegard). A third book (focused on the material recorded in Physica) is in process. Shanon has offered many retreats and educational presentations on the topic of Hildegard and Herbs, including a variety of online classes/seminars and a presentation at the Cleveland Botanical Gardens for the Western Reserve Herb Society.

Shanon Sterringer holds a PhD in Ethical and Creative Leadership (focused on the model of St. Hildegard of Bingen); a DMin, two master’s degrees (MA in theology and MA in ministry), and a BA in Medieval History. She is the founding pastor of the Hildegard Haus in Fairport Harbor, OH, and the owner of The Green Shepherdess Fair-Trade shop and local art studio, also in Fairport Harbor. She has traveled to the Rhine Valley several times since 2015 (most recently in January 2023) to walk in the footsteps of St. Hildegard. She has dedicated the last ten years of her life to studying Hildegard’s charism, most particularly as it relates to holistic health and spirituality. While on sabbatical in 2019, Shanon spent most of the year learning about herbs while working for a local herbalist, Lynn Abbey, at Blue Lake Botanicals in Willoughby, Ohio. Shanon is married and the mother of three adult daughters and has published two books on the topic of Hildegard (Forbidden Grace and 30 Day Journey with St. Hildegard). A third book (focused on the material recorded in Physica) is in process. Shanon has offered many retreats and educational presentations on the topic of Hildegard and Herbs, including a variety of online classes/seminars and a presentation at the Cleveland Botanical Gardens for the Western Reserve Herb Society.