By Katherine Schlosser

For most of us, our garden tools are cleaned and stored, the holidays have passed, and we have a little more time to simply enjoy what we find in meadows, forests, fields, and even in our own backyards. Lichens can fill a part of the void we may be feeling. Their curious forms and means of growing and spreading, with which many of us are unfamiliar, can fill our minds with the wonders of things we normally pass without notice.

There are more than 5,000 species of lichen and lichen-dependent fungi in North America, with colors ranging from blues, lavender, yellow, red, orange, and gray to many beautiful greens. Color in lichens can depend on whether they are wet or dry. A major paint company even created a color they call Lichen to mimic the natural, earthy beauty of the organism. Perfectly described by Ed Yong in a July 2016 issue of The Atlantic, “They can look like flecks of peeling paint, or coralline branches, or dustings of powder, or lettuce-like fronds, or wriggling worms, or cups that a pixie might drink from.”

The forms lichens take are grouped in one of several general types, including:

Foliose – mostly flat with leaf-like structures, with each side having a different appearance

Fruticose – may have tiny “branches” and a bushy appearance

Crustose – appear like flat, crusty painted spots on trees, branches, logs, roof, or rocks

Other forms include:

Filamentous – stringy and hair-like

Gelatinous – jelly-like and somewhat formless

Leprose – have a powdery appearance

Squamulose – small, flat leafy scales with raised tips

Lichens have been used by humans for thousands of years, mostly as medicinals but also as foods, beverages, dyestuffs, cosmetics, brewing, animal fodder—even as an indicator of atmospheric pollution. As useful as they have been, our understanding of lichens has been slow.

Until the late 1800s, lichens were still thought of as plants. In 1868 Simon Schwendener, a Swiss botanist, identified them as a fungus and an alga living in a cooperative relationship. Later botanists recognized the relationship as mutually beneficial, with the alga using sunlight to produce nutrients and the fungus providing shelter, water, and minerals.

Botanists held with the partnership assumption, even though they struggled unsuccessfully to get lichens to grow in the lab. What they were missing was brought to light 150 years later by Tony Spribille, who spent years collecting lichen samples and screening them for genes of basidiomycete fungi.

What had been missed by generations of lichenologists was basidiomycetes, the third member in the partnership of lichens. With the right combination of two fungi and an algal species, a lichen would form. There is much more to learn, but thanks to Spribille, the journey has begun.

Quoting Ed Yong again, Spribille and his associates found that, through a microscope, “a lichen looks like a loaf of ciabatta: it has a stiff, dense crust surrounding a spongy, loose interior. The alga is embedded in the thick crust. The familiar ascomycete fungus is there too, but it branches inwards, creating the spongy interior. And the basidiomycetes? They’re in the outermost part of the crust, surrounding the other two partners. ‘They’re everywhere in that outer layer,’ says Spribille.” And the mystery was solved.

The most frequently noticed are the crustose lichens seen on trees, often looking like someone spray-painted blotches on tree trunks, or left a trail marker. These can vary from shades of gray to greens, blues, and yellows. They are attractive to me but lead some to think their tree has been attacked by disease.

No need to panic; these lichens don’t sink their “teeth” through the bark and into the tree. However, there are some lichens that contribute to the breakdown, or weathering, by physical and chemical processes, of the rocks to which they are attached. Physical effects occur by penetration of the rocks by hyphae and the swelling of organic and inorganic salts. Chemical processes include the “excretion of various organic acids, particularly oxalic acid, which can effectively dissolve minerals” (Chen 2000). The result is the eventual breakdown of rock into the mix of ingredients making our soil.

As an aside, Alexandra Rodrigues and associates inoculated newly created stained glass samples with fungi previously isolated and identified on original stained glass windows. They found that “fungi produced clear damage on all glass surfaces, present as spots and stains, fingerprints, biopitting, leaching and deposition of elements, and formation of biogenic crystals” (Rodrigues et al, 2014). Let that be a warning to keep your stained glass windows clean.

As an aside, Alexandra Rodrigues and associates inoculated newly created stained glass samples with fungi previously isolated and identified on original stained glass windows. They found that “fungi produced clear damage on all glass surfaces, present as spots and stains, fingerprints, biopitting, leaching and deposition of elements, and formation of biogenic crystals” (Rodrigues et al, 2014). Let that be a warning to keep your stained glass windows clean.

Of particular interest to members of The Herb Society of America are the useful aspects of these frequently overlooked species that are building blocks of our green planet. Found growing in moist, shady places, they also thrive in hot, dry lands. Though widely spread across the globe, growing on cold mountaintops to hot deserts on rocks, trees, fallen logs, on fertile soil or dry crust, each species has specific nutrient, air, water, light, and substrate requirements.

They vary widely in usability too, from serving as alerts for the presence of air pollution to providing survival food. Rock tripe, most often seen as green to black leafy-looking masses on boulders, might be the last thing you would consider putting into your mouth, but it turns out that, for thousands of years, they have saved people from starvation. After boiling and draining a few times, they can be made into a soup, even if barely palatable.

One of the more interesting lichens is known as Icelandic moss (Cetraria islandica ), which first came to my attention in the form of Fjallagrasa Icelandic Schnapps. If you look closely at the bottle pictured, you will see a sprig of the lichen in the bottle. Hand picked from the wilderness of Iceland, the lichen is steeped in alcohol, which extracts the color and flavor of the lichen. Sadly, I have not tasted it myself but have heard from a friend, and read, that it is a drink that requires a slight adjustment of expectations. Regardless, I’m almost willing to make the trip to Iceland just for the experience. The manufacturer recommends drinking “in moderation in the company of good friends”—a sound recommendation.

One of the more interesting lichens is known as Icelandic moss (Cetraria islandica ), which first came to my attention in the form of Fjallagrasa Icelandic Schnapps. If you look closely at the bottle pictured, you will see a sprig of the lichen in the bottle. Hand picked from the wilderness of Iceland, the lichen is steeped in alcohol, which extracts the color and flavor of the lichen. Sadly, I have not tasted it myself but have heard from a friend, and read, that it is a drink that requires a slight adjustment of expectations. Regardless, I’m almost willing to make the trip to Iceland just for the experience. The manufacturer recommends drinking “in moderation in the company of good friends”—a sound recommendation.

Beyond alcohol, this particular lichen has multiple medicinal uses, too. The active compounds in Icelandic moss have demonstrated antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal properties (Grujicˇic´ et al., 2014).The mucilaginous compounds (polysaccharides) aid in soothing oral and pharyngeal membranes, relieving coughs of common colds.

Scandinavian countries were long known to use Icelandic moss in making breads and soups. They dried the moss, reconstituted it, then dried it again and ground it to mix into flour. Due to the polysaccharides, the lichen added structure as well as flavor. Many other cultures used it as an addition to flour to cut the expense of flour. Used far less now, over the years, it was an important source of nutrients for many people.

Parmotrema perlatum, commonly known as black stone flower, is used as a spice in India and elsewhere, and is often added to Garam Masala blends. As found, it has no fragrance; exposed to the heat of cooking, it releases an earthy, smoky aroma.

Unlikely as it sounds, some lichens can be fragrant, and some act as a fixative in the preparation of cosmetics and perfumes. Oakmoss lichen, used in perfumery, is found on oak trees, as well as a few other deciduous trees and pines.

A number of lichens are used in the dyeing and tanning industries. If you took high school science, you are familiar with Litmus strips. Those strips are made from litmus, which is obtained from a couple of species of lichens, Roccella tinctoria and Lasallia pustulata.

Winter may be upon us, but there is still plenty to see and study right under our noses in the garden, yard, and out walking on trails. Take notes, take photos, and spend a lazy afternoon identifying what you have found and what uses it may have. Future ventures into the forest will hold considerably more interest for you.

Enjoy!

Medicinal Disclaimer: It is the policy of The Herb Society of America, Inc. not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health use. This information is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an endorsement of any particular medical or health treatment. Please consult a health care provider before pursuing any herbal treatments.

Photo Credits: 1) Old man’s beard (Usnea articulate), a fruticose lichen, photo taken in Linville Falls, NC 2009 (Kathy Schlosser); 2) Lobaria pulmonaria, tree lungwort, used for its astringent properties in tanning, photo taken in Acadia National Park, 2014 (Kathy Schlosser); 3) A foliose rough speckled shield lichen (Punctelia rudecta) covered with isidia (tiny projections which can detach to form new growth and grow from the white spots and streaks), photo taken on the Blue Ridge Parkway, NC 2009 (Kathy Schlosser); 4) Umbilicaria mammulata, smooth rock tripe (Alex Graeff, iNaturalist); 5) A crustose lichen species in Acadia National Park, 2014 (Kathy Schlosser); 6) Pixie cups lichen (Cladonia sp.) growing amongst a cushion moss (Dricanum sp.), 2011 (Kathy Schlosser); 7) Cetraria islandica, Iceland moss (Darya masalova, iNaturalist); 8) Parmotrema caperata (now P. perlatum) as it appears in Flora Batava, vol. 10, 1849 (via Wikimedia); 9) Evernia prunastri, oakmoss lichen used in perfumery (Liondelyon, via Wikimedia)

References

Adams, Ian. Shield lichens at West Woods, Geauga County. Ian Adams Photography website, March 29, 2020. https://ianadamsphotography.com/news/shield-lichens-at-west-woods-geauga-county/ Accessed 12-04-2021.

Cetraria islandica, Iceland moss. https://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Cetraria+islandica Accessed 12-15-2021.

Chen, J., H-P. Blume, and L. Beyer. 2000. Weathering of rocks induced by lichen colonization: A review. CATENA. 39(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0341-8162(99)00085-5. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0341816299000855 Accessed 12-19-2021.

Crawford, S. D. 2015. Lichens used in traditional medicine. Lichen Secondary Metabolites, chapter 2. Springer International Publishing. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-13374-4_2 Accessed 12-28-2021

Daniel, G., and N. Polanin. 2013. Tree-dwelling lichens. Rutgers, N.J. Agricultural Experiment Station. https://njaes.rutgers.edu/fs1205/ Accessed 1-1-2022.

Fink, B. 1906. Lichens: Their economic role. The Plant World. 9(11). Published by Wiley on behalf of the Ecological Society of America. Stable URL:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43476359 Accessed 11-18-2021.

Graeff, Alex. Smooth Rock Tripe, Umbilicaria mammulata. Photo 70633379, iNaturalists, (some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-ND). https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/70633379 Accessed 12-29-2021.

Grujičić, D., I. Stošić, M. Kosanić, T. Stanojković, B. Ranković, and O. Milošević-Djordjević. 2014. Evaluation of in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial, genotoxic and anticancer activities of lichen Cetraria islandica. Cytotechnology. 66(5): 803-813.

Kops, Jan. Flora Batava of Afbeelding en Beschrijving van Nederlandsche Gewassen, (1849). Parmelia caperata, illus. Christiaan Seep, Vol. X, Amsterdam, Deel. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parmelia_caperata_%E2%80%94_Flora_Batava_%E2%80%94_Volume_v10.jpg Accessed 11-09-2021.

Lichen Identification Guide, Discover Life website. https://www.discoverlife.org/mp/20q?guide=Lichens_USGA Accessed 1-1-2022.

Max Planck Society. The hidden talents of mosses and lichens. https://phys.org/news/2021-12-hidden-talents-mosses-lichens.html

Perez-Llano, G. A. 1944. Lichens: Their biological and economic significance. Botanical Review. 10(1). Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4353298 Accessed 12-23-2021.

Perez-Llano, G. S. 1948. Economic uses of lichens. Economic Botany. 2: 15-45.

Rodrigues, A., S. Gutierrez-Patricio, A. Zélia Miller, C. Saiz-Jimenez, R. Wiley, D. Nunes, M. Vilarigues, and M. F. Macedo. 2014. Fungal biodeterioration of stained-glass windows. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2014.03.007. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0964830514000663 Accessed 12-19-2021.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, U./S. Forest Service, Lichens Glossary. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/beauty/lichens/glossary.shtml Accessed 12-04-2021.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service. Lichen Habitat. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/beauty/lichens/habitat.shtml Accessed 12-18-2021.

U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Lichens—The Little Things That Matter https://www.nps.gov/articles/lichen-and-our-air.htm Accessed 12-21-2021.

Yong, E. 2016. How a guy from a Montana trailer park overturned 150 years of biology. The Atlantic, July 22, 2016. http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/07/how-a-guy-from-a-montana-trailer-park-upturned-150-years-of-biology/491702/ Accessed October 2016.

Katherine Schlosser (Kathy) has been a member of the North Carolina Unit of The Herb Society of America since 1991, serving in many capacities at the local and national level, including as a member of the Native Herb Conservation Committee, The Herb Society of America. She was awarded the Gertrude B. Foster Award for Excellence in Herbal Literature and the Helen de Conway Little Medal of Honor. She is an author, lecturer, and native herb conservation enthusiast eager to engage others in the study and protection of our native herbs.

Dill, Anethum graveolens, has been grown and used for thousands of years. Dill is a native of the Mediterranean area and is an important part of northern European cuisines. It is an annual herb that will reseed if it likes where it is growing, and is one of the first herbs to appear in the spring garden. The foliage, often referred to as “dillweed,” is a tasty addition to fish, chicken, eggs, cucumber, and potato dishes. The yellow flowers that form on top of 2-3 foot stems appear in clusters which then become the seeds. The seeds are ready to harvest when brown and are used in pickling, vinegars, breads, and crackers.

Dill, Anethum graveolens, has been grown and used for thousands of years. Dill is a native of the Mediterranean area and is an important part of northern European cuisines. It is an annual herb that will reseed if it likes where it is growing, and is one of the first herbs to appear in the spring garden. The foliage, often referred to as “dillweed,” is a tasty addition to fish, chicken, eggs, cucumber, and potato dishes. The yellow flowers that form on top of 2-3 foot stems appear in clusters which then become the seeds. The seeds are ready to harvest when brown and are used in pickling, vinegars, breads, and crackers.  Many European and Asian cultures used dill for its medicinal qualities. In fact, the word “dill” stems from the Norse word “dilla” which means to lull or soothe. Indeed, some of its oldest medicinal uses (for which it’s still used today) were to soothe stomach problems, aid insomnia, and increase lactation in breastfeeding women. Traditional and Ayurvedic medicines today recommend “gripe water,” an infusion of dill seed in water, as a sleep and digestive aid, especially for children. Dill is more commonly used in Europe and Asia as a medicine than in the US. There is ongoing research to verify the traditional medicinal applications of the herb. According to Nutrition Today, “recent clinical trials evaluated dill and its extracts for managing risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as in improving outcomes during labor and delivery.“ One author states: “Talk about a useful organism – dill has also been known to stop the growth of certain bacterium such as E. coli, and streptococcus (staph infection)!” (Krumke, 2012).

Many European and Asian cultures used dill for its medicinal qualities. In fact, the word “dill” stems from the Norse word “dilla” which means to lull or soothe. Indeed, some of its oldest medicinal uses (for which it’s still used today) were to soothe stomach problems, aid insomnia, and increase lactation in breastfeeding women. Traditional and Ayurvedic medicines today recommend “gripe water,” an infusion of dill seed in water, as a sleep and digestive aid, especially for children. Dill is more commonly used in Europe and Asia as a medicine than in the US. There is ongoing research to verify the traditional medicinal applications of the herb. According to Nutrition Today, “recent clinical trials evaluated dill and its extracts for managing risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as in improving outcomes during labor and delivery.“ One author states: “Talk about a useful organism – dill has also been known to stop the growth of certain bacterium such as E. coli, and streptococcus (staph infection)!” (Krumke, 2012).  Besides being used in the food industry to make dill pickles, dill also flavors some Aquavit liqueurs and is used to perfume cosmetics, detergents, mouthwashes, and soaps.

Besides being used in the food industry to make dill pickles, dill also flavors some Aquavit liqueurs and is used to perfume cosmetics, detergents, mouthwashes, and soaps.

Cutting celery is a great culinary herb to have in your garden. Unlike stalk celery from a grocery store, cutting celery is full of flavor, reminiscent of black pepper. Cutting celery (

Cutting celery is a great culinary herb to have in your garden. Unlike stalk celery from a grocery store, cutting celery is full of flavor, reminiscent of black pepper. Cutting celery ( Once you start cooking with cutting celery, you realize its value as a kitchen staple. I cut stems as I need them and chop leaves and stems together simply because it is easiest. I add the mix to stir fry dishes, soups, stews, egg dishes and potato recipes toward the end of the cooking period. Sometimes I add about a spoonful to a green salad to add a peppery flavor in small amounts. I also sauté chopped celery with diced green pepper and tomato to add to fish or chicken. The leaves can be used as a garnish. I like to place a bunch under an entrée such as a whole roasted chicken on a platter.

Once you start cooking with cutting celery, you realize its value as a kitchen staple. I cut stems as I need them and chop leaves and stems together simply because it is easiest. I add the mix to stir fry dishes, soups, stews, egg dishes and potato recipes toward the end of the cooking period. Sometimes I add about a spoonful to a green salad to add a peppery flavor in small amounts. I also sauté chopped celery with diced green pepper and tomato to add to fish or chicken. The leaves can be used as a garnish. I like to place a bunch under an entrée such as a whole roasted chicken on a platter. Peggy Riccio is the owner of pegplant.com, an online resource for gardening in the Washington, D.C. metro area; past president of the Potomac Unit; and current mid-Atlantic District Delegate of the Herb Society of America.

Peggy Riccio is the owner of pegplant.com, an online resource for gardening in the Washington, D.C. metro area; past president of the Potomac Unit; and current mid-Atlantic District Delegate of the Herb Society of America. Cumin,

Cumin,  Cumin is an annual herb in the parsley family (Apiaceae). The seed that it produces is also called cumin. It requires a long, warm growing season of 120-150 days to produce the seed. In cooler climates seeds can be started indoors and then transplanted into the garden, although they may not transplant well. Cumin needs full sun and fertile, well-draining soil. Root rot can be a problem if the soil does not drain well. The plant reaches a height of about one foot tall and has feathery looking leaves and pink or white flowers. The seeds are small and boat-shaped with ridges and are very fragrant. They look similar to caraway seeds. Cumin is available as a whole seed or as a powder. Fresh leaves of the plant can be chopped and tossed into salads.

Cumin is an annual herb in the parsley family (Apiaceae). The seed that it produces is also called cumin. It requires a long, warm growing season of 120-150 days to produce the seed. In cooler climates seeds can be started indoors and then transplanted into the garden, although they may not transplant well. Cumin needs full sun and fertile, well-draining soil. Root rot can be a problem if the soil does not drain well. The plant reaches a height of about one foot tall and has feathery looking leaves and pink or white flowers. The seeds are small and boat-shaped with ridges and are very fragrant. They look similar to caraway seeds. Cumin is available as a whole seed or as a powder. Fresh leaves of the plant can be chopped and tossed into salads. Cumin seeds have been discovered in 4,000-year-old excavations in Syria and Egypt. Cumin was used in the mummification process of Egyptian pharaohs. References to cumin are found in the Bible, both the New and Old Testaments. During Roman times, it was associated with being frugal with money. Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor from 161-180 AD, had the nickname Marcus Cuminus because his subjects thought he was reluctant to spend money. In the Middle Ages, cumin was baked into bread, and it was thought that eating this bread would keep a lover faithful. Soldiers carried it in their pockets for good luck and people fed it to chickens thinking that it kept them from wandering away (Great American Spice Company, 2020). The Hindus considered cumin to be a symbol of fidelity. Cumin was used to pay rent in 13

Cumin seeds have been discovered in 4,000-year-old excavations in Syria and Egypt. Cumin was used in the mummification process of Egyptian pharaohs. References to cumin are found in the Bible, both the New and Old Testaments. During Roman times, it was associated with being frugal with money. Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor from 161-180 AD, had the nickname Marcus Cuminus because his subjects thought he was reluctant to spend money. In the Middle Ages, cumin was baked into bread, and it was thought that eating this bread would keep a lover faithful. Soldiers carried it in their pockets for good luck and people fed it to chickens thinking that it kept them from wandering away (Great American Spice Company, 2020). The Hindus considered cumin to be a symbol of fidelity. Cumin was used to pay rent in 13 There were medicinal uses for cumin in early history. Early Egyptians used it to treat digestive and chest issues and for reducing pain. Fourth and fifth century BC Greek medical texts show that cumin was used for women’s reproductive problems and to treat hysteria. Medicinal use of cumin was popular throughout the Middle Ages. Today, cumin is used in Ayurvedic medicine as a stimulant for digestion and is prescribed for colic and dyspepsia. It is also still used in Egyptian and Chinese herbal medicine.

There were medicinal uses for cumin in early history. Early Egyptians used it to treat digestive and chest issues and for reducing pain. Fourth and fifth century BC Greek medical texts show that cumin was used for women’s reproductive problems and to treat hysteria. Medicinal use of cumin was popular throughout the Middle Ages. Today, cumin is used in Ayurvedic medicine as a stimulant for digestion and is prescribed for colic and dyspepsia. It is also still used in Egyptian and Chinese herbal medicine.

Caraway seed,

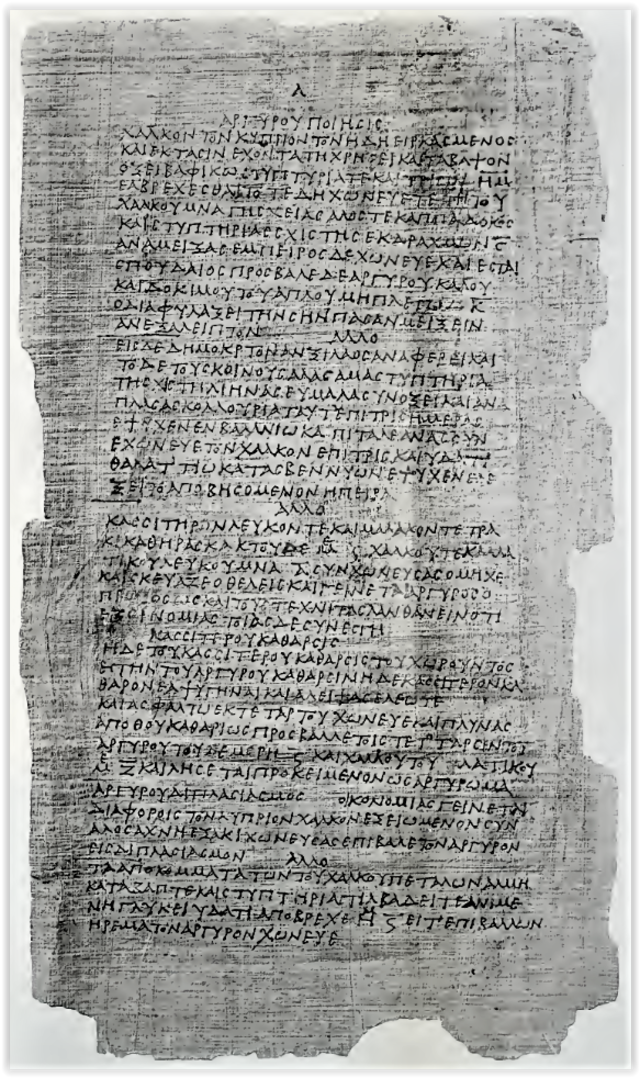

Caraway seed,  References to caraway are found in the Ebers Papyrus (1500 BCE) and in the writings of the Greek physician, Dioscorides (50-70 CE). Some trace its use back to the Stone Age because fossilized seeds have been found around lake dwellings from that period. The Romans used caraway and spread its use to other parts of their realm. It has been cultivated in Europe since the Middle Ages.

References to caraway are found in the Ebers Papyrus (1500 BCE) and in the writings of the Greek physician, Dioscorides (50-70 CE). Some trace its use back to the Stone Age because fossilized seeds have been found around lake dwellings from that period. The Romans used caraway and spread its use to other parts of their realm. It has been cultivated in Europe since the Middle Ages.  The culinary use of caraway is well known. Caraway is used to make the north African chile sauce, harissa. It is also used in the traditional British seed cake that is enjoyed with tea (Marchetti, 2013). Its anise-like flavor is very popular in German and Slavic cuisines. The seed is used to flavor breads such as Jewish rye bread, sausages, cabbage, and fruit and vegetable dishes as well as cheeses such as Havarti. The leaves are added to soups and salads. The seeds are also used to make alcoholic drinks such as aquavit, kϋmmel, and vodka. The seeds can be sugar coated and used as a breath freshener or a digestive aid. The essential oil is used in perfumes, ice cream, candy, soft drinks, and to flavor children’s medicine (Bown, 2001). Growing up in a Slavic household, caraway seed was a staple spice in my mom’s kitchen.

The culinary use of caraway is well known. Caraway is used to make the north African chile sauce, harissa. It is also used in the traditional British seed cake that is enjoyed with tea (Marchetti, 2013). Its anise-like flavor is very popular in German and Slavic cuisines. The seed is used to flavor breads such as Jewish rye bread, sausages, cabbage, and fruit and vegetable dishes as well as cheeses such as Havarti. The leaves are added to soups and salads. The seeds are also used to make alcoholic drinks such as aquavit, kϋmmel, and vodka. The seeds can be sugar coated and used as a breath freshener or a digestive aid. The essential oil is used in perfumes, ice cream, candy, soft drinks, and to flavor children’s medicine (Bown, 2001). Growing up in a Slavic household, caraway seed was a staple spice in my mom’s kitchen.  Bay laurel,

Bay laurel,

Propagating bay takes patience as it is very slow to germinate and grow. The Herb Society of America’s guide to bay offers a method for propagating bay laurel.

Propagating bay takes patience as it is very slow to germinate and grow. The Herb Society of America’s guide to bay offers a method for propagating bay laurel. Bay laurel branches are pliable and lend themselves to making wreaths. The leaves are also used for potpourri. Many of us remember the old-fashioned way of keeping flour and grains insect-proof by adding a bay leaf or two to the container. The essential oil of bay is used in perfumes and soaps.

Bay laurel branches are pliable and lend themselves to making wreaths. The leaves are also used for potpourri. Many of us remember the old-fashioned way of keeping flour and grains insect-proof by adding a bay leaf or two to the container. The essential oil of bay is used in perfumes and soaps.

As an aside, Alexandra Rodrigues and associates inoculated newly created stained glass samples with fungi previously isolated and identified on original stained glass windows. They found that “fungi produced clear damage on all glass surfaces, present as spots and stains, fingerprints, biopitting, leaching and deposition of elements, and formation of biogenic crystals” (Rodrigues et al, 2014). Let that be a warning to keep your stained glass windows clean.

As an aside, Alexandra Rodrigues and associates inoculated newly created stained glass samples with fungi previously isolated and identified on original stained glass windows. They found that “fungi produced clear damage on all glass surfaces, present as spots and stains, fingerprints, biopitting, leaching and deposition of elements, and formation of biogenic crystals” (Rodrigues et al, 2014). Let that be a warning to keep your stained glass windows clean.  One of the more interesting lichens is known as Icelandic moss (

One of the more interesting lichens is known as Icelandic moss (

It is summer and a perfect time to learn about summer savory,

It is summer and a perfect time to learn about summer savory,  Savory is native to southern Europe and northern Africa. It was a very popular herb for the Romans until black pepper was introduced. The Roman writer Pliny (23 CE) is credited with giving the plant its Latin name,

Savory is native to southern Europe and northern Africa. It was a very popular herb for the Romans until black pepper was introduced. The Roman writer Pliny (23 CE) is credited with giving the plant its Latin name,  Herbes de Provence

Herbes de Provence Historically, savory has been used as a “tonic, vermifuge, appetite stimulant, and a treatment for diarrhea. A tea has been used as an expectorant and as a cough remedy” (Kowalchik & Hylton, 1998). Ancient gardeners and today’s gardeners alike have used the crushed leaves to relieve the sting of insect bites. Recent research indicates that because of

Historically, savory has been used as a “tonic, vermifuge, appetite stimulant, and a treatment for diarrhea. A tea has been used as an expectorant and as a cough remedy” (Kowalchik & Hylton, 1998). Ancient gardeners and today’s gardeners alike have used the crushed leaves to relieve the sting of insect bites. Recent research indicates that because of