By Chrissy Moore

One of the enchanting things about working in the National Herb Garden is the myriad people I meet from around the world. Ne’er a week goes by that I don’t see or get to speak with someone personally from another country. I’m often brazen enough to confront people directly and, figuratively speaking, “pat them down” for herbal information from their homeland!

One of the enchanting things about working in the National Herb Garden is the myriad people I meet from around the world. Ne’er a week goes by that I don’t see or get to speak with someone personally from another country. I’m often brazen enough to confront people directly and, figuratively speaking, “pat them down” for herbal information from their homeland!

Just such an opportunity presented itself this past summer. As I was sitting on a bench awaiting my coworker for a brief meeting, I noticed a woman and her teenage daughter walking through the garden. I got up the nerve to ask her where they were from. The mother was Thai, while her daughter was Thai/Maltese, the father being from Malta. I asked the mother (her name was Dao), if I could inquire about plants from her homeland, and so began her almost two-hour tour around the garden…the garden that I have worked in for over 25 years! Whoever said you “learn new things every day” wasn’t lying. Dao enthusiastically recounted stories of how the people from her village used such-and-such plant “back when I grew up and we had no electricity!”

While not all of the plants she discussed with me are currently in our inventory, I learned that they should be, and I’ll do my darndest to find them. But, mostly, she pointed out the plants that we already had, so I’ll start with a popular fruit tree, Carica papaya.

Papaya is a small tree, relatively speaking, growing to about 30 feet tall. Interestingly, it only lives for five to ten years, which is pretty short in tree years. It has deeply lobed leaves reminiscent of fig leaves (Ficus carica), hence the obvious relationship with fig’s specific epithet. Generally, Carica is dioecious, meaning the male and female flowers are on separate trees, and the tree will start bearing fruit in one year to 18 months from seed. The resulting fruit can be anywhere from three to 20 inches long and can weigh in at a hefty 20 – 25 lbs! The fruit’s skin turns from green to yellow when ripe, and the flesh is a lovely tropical yellow to orange and is filled with hundreds of wrinkly black seeds (Britannica, 2022). While most people consume just the papaya flesh or juice, there’s no need to throw those seeds away; they have a strong, pepper-like flavor and can be used as a spice in various culinary preparations.

Papaya is a small tree, relatively speaking, growing to about 30 feet tall. Interestingly, it only lives for five to ten years, which is pretty short in tree years. It has deeply lobed leaves reminiscent of fig leaves (Ficus carica), hence the obvious relationship with fig’s specific epithet. Generally, Carica is dioecious, meaning the male and female flowers are on separate trees, and the tree will start bearing fruit in one year to 18 months from seed. The resulting fruit can be anywhere from three to 20 inches long and can weigh in at a hefty 20 – 25 lbs! The fruit’s skin turns from green to yellow when ripe, and the flesh is a lovely tropical yellow to orange and is filled with hundreds of wrinkly black seeds (Britannica, 2022). While most people consume just the papaya flesh or juice, there’s no need to throw those seeds away; they have a strong, pepper-like flavor and can be used as a spice in various culinary preparations.

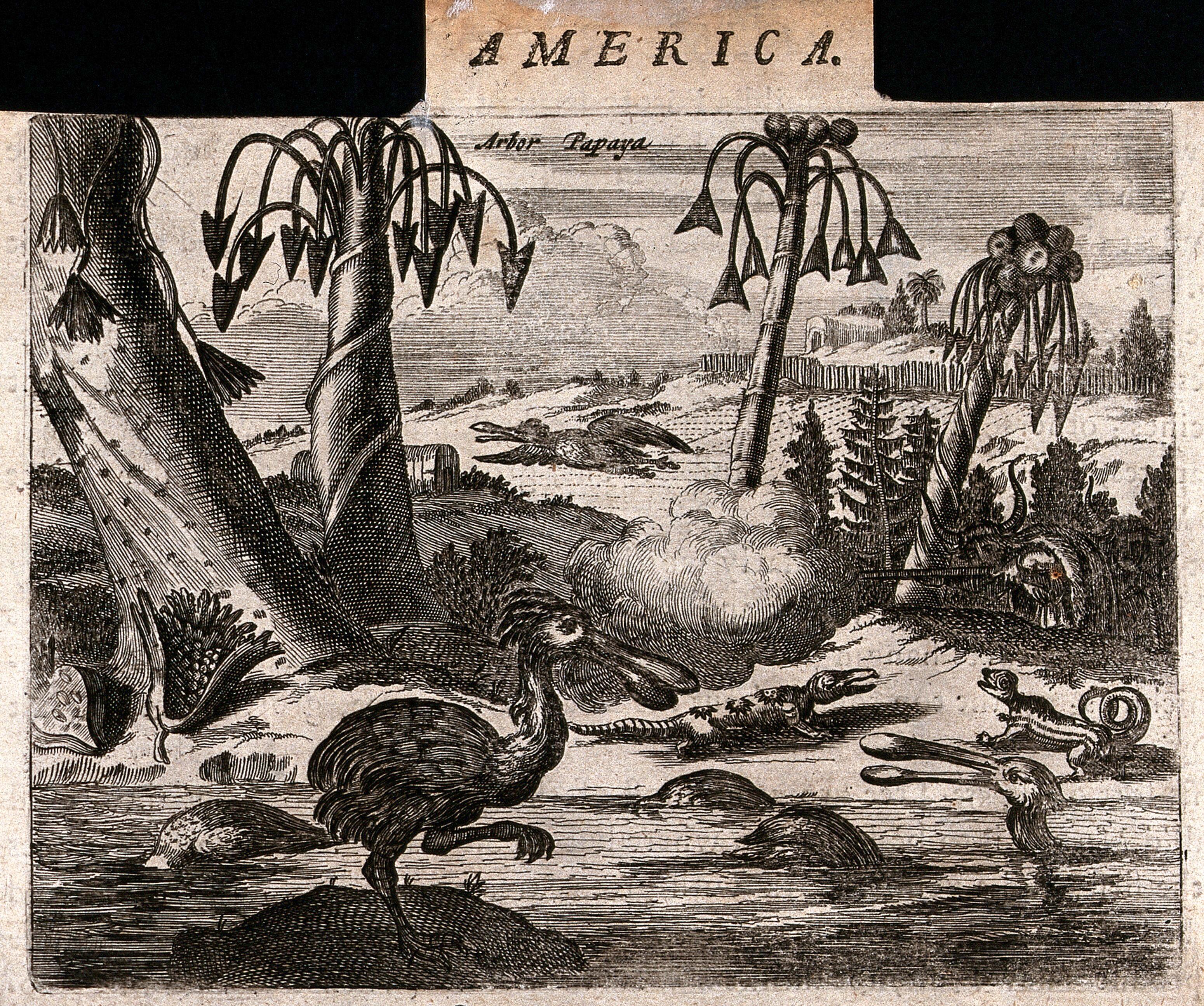

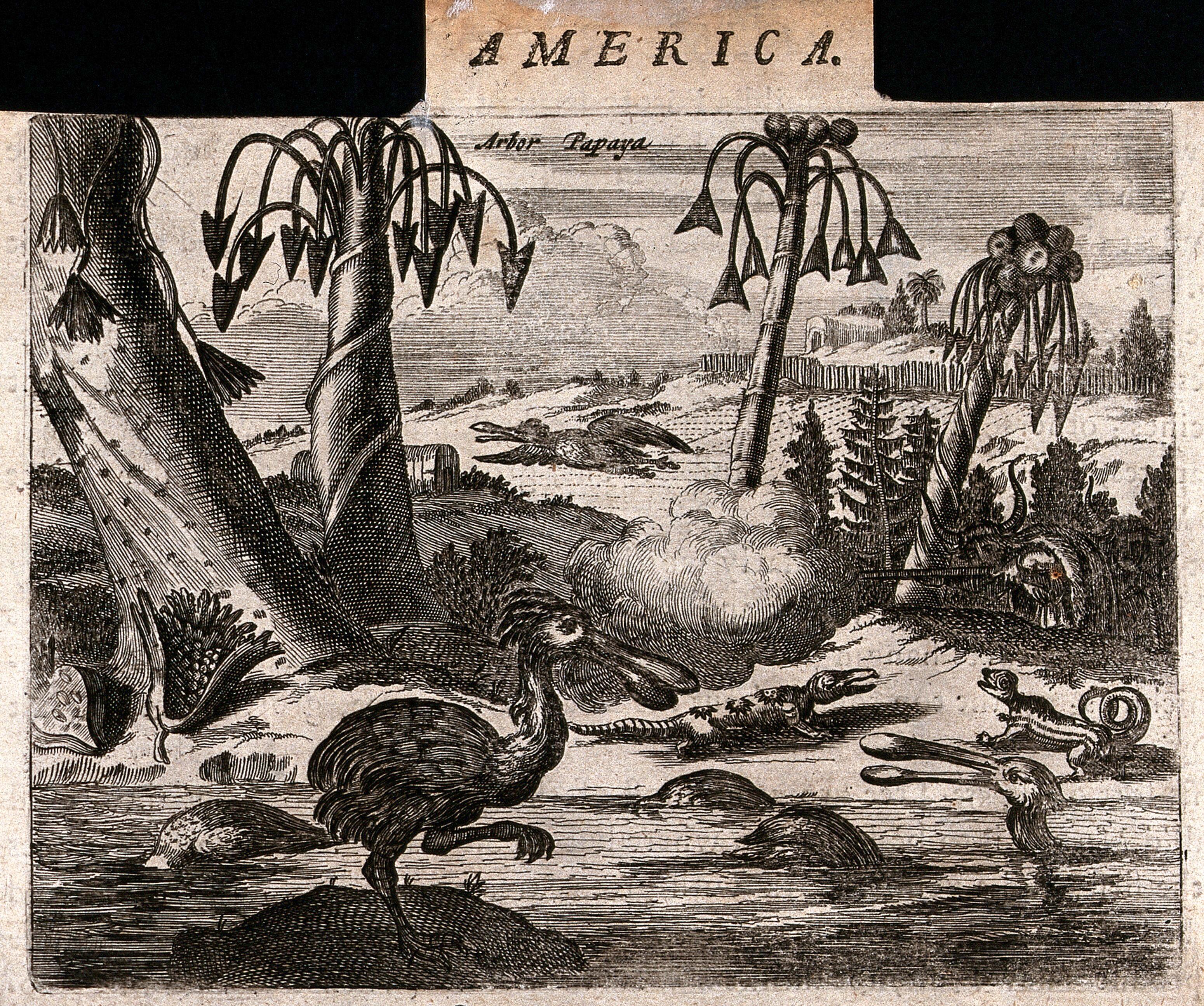

The juice can be found in numerous commercial brands, particularly those from Latin and South America. In fact, papaya is native to Central and South America, not Southeast Asia, which may seem odd given this article is about Thai herbs. Let’s just say that papaya is well-traveled (unlike me). It has a long history of being moved from one country to another, then to another, each time being propagated, and then shipped off again to yet another tropical part of the world. The Spanish chronicler, Oviedo, first described Carica papaya in 1526 A.D. In the early 1600s, Spanish explorers to the New World carried the seed to Panama and the Dominican Republic. From the Caribbean, Spanish and Portuguese sailors carried the seeds to Southeast Asia and India, to Australia and even to Italy. Between 1800 – 1820, papaya was sent on to Hawaii, and by 1900, papaya had come all the way back to the New World, landing in Florida. In all of these locations, it was introduced as a plantation, or agricultural, crop (TFNetwork, 2016). “Papaya has become an important agricultural export for developing countries, where export revenues of the fruit provide a livelihood for thousands of people, especially in Asia and Latin America” (Evans and Ballen, 2018).

The juice can be found in numerous commercial brands, particularly those from Latin and South America. In fact, papaya is native to Central and South America, not Southeast Asia, which may seem odd given this article is about Thai herbs. Let’s just say that papaya is well-traveled (unlike me). It has a long history of being moved from one country to another, then to another, each time being propagated, and then shipped off again to yet another tropical part of the world. The Spanish chronicler, Oviedo, first described Carica papaya in 1526 A.D. In the early 1600s, Spanish explorers to the New World carried the seed to Panama and the Dominican Republic. From the Caribbean, Spanish and Portuguese sailors carried the seeds to Southeast Asia and India, to Australia and even to Italy. Between 1800 – 1820, papaya was sent on to Hawaii, and by 1900, papaya had come all the way back to the New World, landing in Florida. In all of these locations, it was introduced as a plantation, or agricultural, crop (TFNetwork, 2016). “Papaya has become an important agricultural export for developing countries, where export revenues of the fruit provide a livelihood for thousands of people, especially in Asia and Latin America” (Evans and Ballen, 2018).

Today, Mexico has moved into first place as the number one exporter of papaya, with virtually all of its exports going to the United States, which “ranks as the largest importer of papayas globally” (FAO, 2021). Who knew?! So, I guess it isn’t that surprising that it was here in the United States–not Thailand–that I met Dao who shared with me about one of the most popular tropical plants in her home country, as well as mine.

Today, Mexico has moved into first place as the number one exporter of papaya, with virtually all of its exports going to the United States, which “ranks as the largest importer of papayas globally” (FAO, 2021). Who knew?! So, I guess it isn’t that surprising that it was here in the United States–not Thailand–that I met Dao who shared with me about one of the most popular tropical plants in her home country, as well as mine.

According to Dao, the green (unripe) fruit is used as a vegetable to make papaya salad, and it can also be fried with meat. If boiled with meat, it makes the meat softer and more moist. The leaves, she explained, are eaten in Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos, where they are cut and fried or eaten raw. Medicinally, papaya is considered by many Thai as an old-fashioned remedy good for the body, diabetes, and cancer. The leaf juice was/is used to treat intestinal cancer, and the ripe fruit is good for relieving constipation (personal communication).

According to Dao, the green (unripe) fruit is used as a vegetable to make papaya salad, and it can also be fried with meat. If boiled with meat, it makes the meat softer and more moist. The leaves, she explained, are eaten in Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos, where they are cut and fried or eaten raw. Medicinally, papaya is considered by many Thai as an old-fashioned remedy good for the body, diabetes, and cancer. The leaf juice was/is used to treat intestinal cancer, and the ripe fruit is good for relieving constipation (personal communication).

Much of this makes perfect sense when you analyze the chemical constituents of papaya. It is rich in antioxidants, vitamins, and fiber (UFL/IFAS, 2016). The Tropical Fruit Network states, “Furthermore, papaya also contains [potassium, copper, phosphorus, iron, and manganese], carotenes, flavonoids, folate and pantothenic acid, and also fiber. These nutrients help to promote a healthy cardiovascular system and provide protection against colon cancer. Fiber has been shown to lower cholesterol level[s] in [the] human body. Papaya and its seeds have proven anti-parasitic and anti-amoebic activities, and their consumption offers a cheap, natural, harmless, readily available preventive strategy against intestinal parasites.” What scientists have lately confirmed, the people of Thailand have been putting into practice for centuries.

Both the papaya leaves and the fruit’s skin produce a latex substance from which a digestive enzyme called papain can be obtained. Papain is similar to the human digestive enzyme pepsin, and thus, is an effective plant-based meat tenderizer, “useful in digesting or coagulating, clotting, and converting proteins into smaller parts” (Tyler et al., 1988). (Bromelain, an enzyme from pineapples, is used similarly.) Hence, the Thai method of mixing papaya with meat effectively tenderizes the meat during the cooking process. (Note: If one has a latex allergy, caution should be used.)

Both the papaya leaves and the fruit’s skin produce a latex substance from which a digestive enzyme called papain can be obtained. Papain is similar to the human digestive enzyme pepsin, and thus, is an effective plant-based meat tenderizer, “useful in digesting or coagulating, clotting, and converting proteins into smaller parts” (Tyler et al., 1988). (Bromelain, an enzyme from pineapples, is used similarly.) Hence, the Thai method of mixing papaya with meat effectively tenderizes the meat during the cooking process. (Note: If one has a latex allergy, caution should be used.)

Such uses transcend “old-fashioned” methods by including modern applications as well. Papain is used in some contact lens cleaning solutions (Tyler et al., 1988), as well as in the production of products like chewing gum, shampoo and soap, beer, in drug and anti-bacterial preparations for some digestive ailments, and in wound care. Papaya extracts are also effective in the textile industry for “degumming silk and softening of wool” (TFNetwork, 2016). In 2021, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center also noted on their website that “papaya leaves and their extracts are sold as dietary supplements to improve the immune system and increase platelet counts….A few clinical studies found benefits of papaya leaf extract in treating dengue fever and in increasing platelet counts,” though they suggested that more studies were needed.

Such uses transcend “old-fashioned” methods by including modern applications as well. Papain is used in some contact lens cleaning solutions (Tyler et al., 1988), as well as in the production of products like chewing gum, shampoo and soap, beer, in drug and anti-bacterial preparations for some digestive ailments, and in wound care. Papaya extracts are also effective in the textile industry for “degumming silk and softening of wool” (TFNetwork, 2016). In 2021, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center also noted on their website that “papaya leaves and their extracts are sold as dietary supplements to improve the immune system and increase platelet counts….A few clinical studies found benefits of papaya leaf extract in treating dengue fever and in increasing platelet counts,” though they suggested that more studies were needed.

In my small world, papaya has always been “that fruit” (or juice) that I’ve never actually tried and for no particular reason. Fortunately for me, I learned something new that day–that papaya is not just a one-trick pony as I had previously thought; there are plenty of ways this plant is useful to humans, especially for people like Dao from Thailand. Having the opportunity to speak with people like her who have such personal relationships with many of the herbs we grow in the National Herb Garden never gets old!

In my small world, papaya has always been “that fruit” (or juice) that I’ve never actually tried and for no particular reason. Fortunately for me, I learned something new that day–that papaya is not just a one-trick pony as I had previously thought; there are plenty of ways this plant is useful to humans, especially for people like Dao from Thailand. Having the opportunity to speak with people like her who have such personal relationships with many of the herbs we grow in the National Herb Garden never gets old!

Medicinal Disclaimer: It is the policy of The Herb Society of America, Inc. not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health use. This information is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an endorsement of any particular medical or health treatment. Please consult a health care provider before pursuing any herbal treatments.

Photo Credits: 1) Carica papaya immature tree with fruit (Creative Commons, Bmdavll@EnglishWikipedia); 2) Papaya leaf (Creative Commons, Marufish); 3) Ripe papaya fruit with seeds (Creative Commons, love.jsc); 4) 1671 etching of Carica papaya trees (Public Domain); 5) Thai papaya salad (Creative Commons, Ken2754@yokohama); 6) Strips of papaya being used as a meat tenderizer (Creative Commons, Thai Food Blog); 7) Papaya extract (Public Domain); 8) Papaya fruit and juice (Bincy Lenin’s Kitchen, youtube).

References

Britannica Online. 2022. Papaya. Accessed 28 Dec 2022. https://www.britannica.com/plant/papaya.

Evans, Edward A. and Fredy H. Ballen. 2018. An overview of global papaya production, trade, and consumption. University of Florida, Food and Resource Economics Department, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Extension. Accessed 12 Dec 2022. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FE913.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2021. International Trade Major Tropical Fruits: preliminary results 2021, p. 13. Accessed 28 Dec 2022. https://www.fao.org/3/cb9412en/cb9412en.pdf

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. 2021. Papaya leaf: Purported benefits, side effects, and more. Accessed 7 Jan 2023. https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/herbs/papaya-leaf

Tyler, Varro E., Lynn Brady, and James Robbers. 1988. Pharmacognosy. 9th Edition. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

TFNet News Compilation. 2016. Papaya – Introduction. International Tropical Fruits Network. Accessed 28 Dec 2022. https://www.itfnet.org/v1/2016/05/papaya-introduction/

Chrissy Moore is the curator of the National Herb Garden at the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington, DC. Aside from garden maintenance in the NHG, Chrissy lectures, provides tours, and writes on various herbal topics. She serves as co-blogmaster of The Herb Society’s blog and is a member of the Potomac Unit of The Herb Society of America. Chrissy is also an International Society of Arboriculture certified arborist. When not doing herbie things, she can be found looking after many horses.

West Indian lemongrass, Cymbopogon citratus, is a fragrant member of the grass family (Poaceae). It has long, sharp-edged, narrow leaves and edible, small bulbous roots that resemble scallions. The plant is used as an ornamental grass in the garden, growing quite tall in a single season. It is evergreen in Zones 10 and 11, and the roots are winter hardy to Zones 8b, if protected. The foliage turns brown in the winter and should be trimmed back in the spring before new growth starts. It is an annual plant in zones lower than 8b.

West Indian lemongrass, Cymbopogon citratus, is a fragrant member of the grass family (Poaceae). It has long, sharp-edged, narrow leaves and edible, small bulbous roots that resemble scallions. The plant is used as an ornamental grass in the garden, growing quite tall in a single season. It is evergreen in Zones 10 and 11, and the roots are winter hardy to Zones 8b, if protected. The foliage turns brown in the winter and should be trimmed back in the spring before new growth starts. It is an annual plant in zones lower than 8b. Lemongrass can be grown from seed, or the crown and rhizome can be divided to create new plants. New plants can also be started from stalks purchased from a grocery store’s produce section. It rarely produces a flower when grown as an annual plant. It needs full sun, fertile soil, and adequate water and will grow easily in a container.

Lemongrass can be grown from seed, or the crown and rhizome can be divided to create new plants. New plants can also be started from stalks purchased from a grocery store’s produce section. It rarely produces a flower when grown as an annual plant. It needs full sun, fertile soil, and adequate water and will grow easily in a container. In India, the plant is used mostly for medicine. It is believed to have cooling properties and is sometimes called “fever grass.” It is used to treat stomachaches, digestive problems, and inflammation (Stephanie Lyon, N.D.). Lemongrass tea is thought to be antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant, and is also considered to be calming. Lemongrass is high in Vitamin A and is used in the “compounding of vitamins” (Madeline Hill, 1997). More research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of lemongrass on illness.

In India, the plant is used mostly for medicine. It is believed to have cooling properties and is sometimes called “fever grass.” It is used to treat stomachaches, digestive problems, and inflammation (Stephanie Lyon, N.D.). Lemongrass tea is thought to be antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant, and is also considered to be calming. Lemongrass is high in Vitamin A and is used in the “compounding of vitamins” (Madeline Hill, 1997). More research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of lemongrass on illness. The essential oil is also used by beekeepers to imitate a pheromone to attract bees to the hive or swarm (Hobbs, 2022).

The essential oil is also used by beekeepers to imitate a pheromone to attract bees to the hive or swarm (Hobbs, 2022).

Cumin,

Cumin,  Cumin is an annual herb in the parsley family (Apiaceae). The seed that it produces is also called cumin. It requires a long, warm growing season of 120-150 days to produce the seed. In cooler climates seeds can be started indoors and then transplanted into the garden, although they may not transplant well. Cumin needs full sun and fertile, well-draining soil. Root rot can be a problem if the soil does not drain well. The plant reaches a height of about one foot tall and has feathery looking leaves and pink or white flowers. The seeds are small and boat-shaped with ridges and are very fragrant. They look similar to caraway seeds. Cumin is available as a whole seed or as a powder. Fresh leaves of the plant can be chopped and tossed into salads.

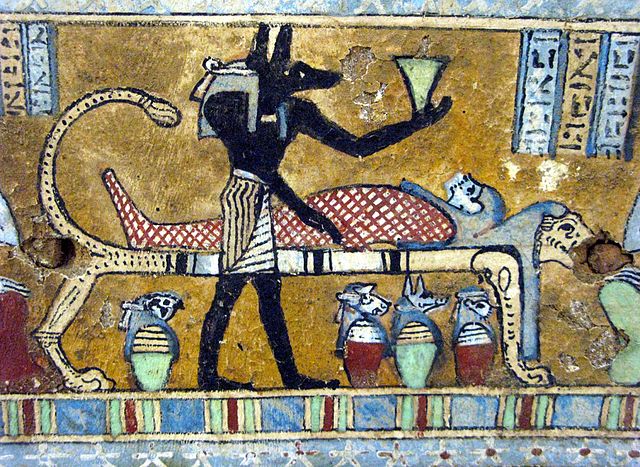

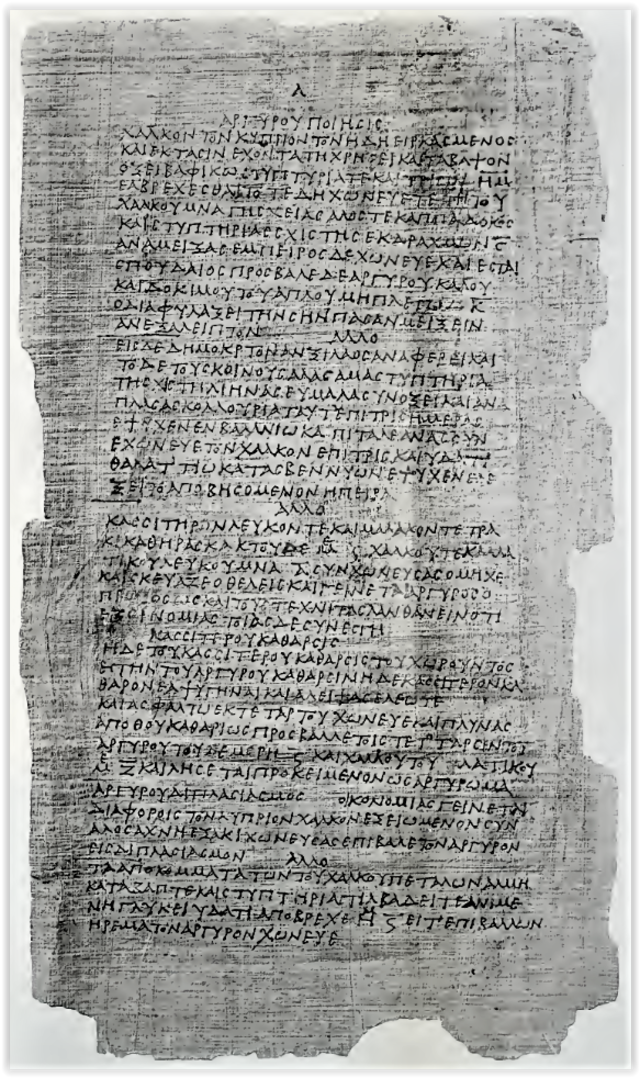

Cumin is an annual herb in the parsley family (Apiaceae). The seed that it produces is also called cumin. It requires a long, warm growing season of 120-150 days to produce the seed. In cooler climates seeds can be started indoors and then transplanted into the garden, although they may not transplant well. Cumin needs full sun and fertile, well-draining soil. Root rot can be a problem if the soil does not drain well. The plant reaches a height of about one foot tall and has feathery looking leaves and pink or white flowers. The seeds are small and boat-shaped with ridges and are very fragrant. They look similar to caraway seeds. Cumin is available as a whole seed or as a powder. Fresh leaves of the plant can be chopped and tossed into salads. Cumin seeds have been discovered in 4,000-year-old excavations in Syria and Egypt. Cumin was used in the mummification process of Egyptian pharaohs. References to cumin are found in the Bible, both the New and Old Testaments. During Roman times, it was associated with being frugal with money. Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor from 161-180 AD, had the nickname Marcus Cuminus because his subjects thought he was reluctant to spend money. In the Middle Ages, cumin was baked into bread, and it was thought that eating this bread would keep a lover faithful. Soldiers carried it in their pockets for good luck and people fed it to chickens thinking that it kept them from wandering away (Great American Spice Company, 2020). The Hindus considered cumin to be a symbol of fidelity. Cumin was used to pay rent in 13

Cumin seeds have been discovered in 4,000-year-old excavations in Syria and Egypt. Cumin was used in the mummification process of Egyptian pharaohs. References to cumin are found in the Bible, both the New and Old Testaments. During Roman times, it was associated with being frugal with money. Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor from 161-180 AD, had the nickname Marcus Cuminus because his subjects thought he was reluctant to spend money. In the Middle Ages, cumin was baked into bread, and it was thought that eating this bread would keep a lover faithful. Soldiers carried it in their pockets for good luck and people fed it to chickens thinking that it kept them from wandering away (Great American Spice Company, 2020). The Hindus considered cumin to be a symbol of fidelity. Cumin was used to pay rent in 13 There were medicinal uses for cumin in early history. Early Egyptians used it to treat digestive and chest issues and for reducing pain. Fourth and fifth century BC Greek medical texts show that cumin was used for women’s reproductive problems and to treat hysteria. Medicinal use of cumin was popular throughout the Middle Ages. Today, cumin is used in Ayurvedic medicine as a stimulant for digestion and is prescribed for colic and dyspepsia. It is also still used in Egyptian and Chinese herbal medicine.

There were medicinal uses for cumin in early history. Early Egyptians used it to treat digestive and chest issues and for reducing pain. Fourth and fifth century BC Greek medical texts show that cumin was used for women’s reproductive problems and to treat hysteria. Medicinal use of cumin was popular throughout the Middle Ages. Today, cumin is used in Ayurvedic medicine as a stimulant for digestion and is prescribed for colic and dyspepsia. It is also still used in Egyptian and Chinese herbal medicine.

One of the enchanting things about working in the National Herb Garden is the myriad people I meet from around the world. Ne’er a week goes by that I don’t see or get to speak with someone personally from another country. I’m often brazen enough to confront people directly and, figuratively speaking, “pat them down” for herbal information from their homeland!

One of the enchanting things about working in the National Herb Garden is the myriad people I meet from around the world. Ne’er a week goes by that I don’t see or get to speak with someone personally from another country. I’m often brazen enough to confront people directly and, figuratively speaking, “pat them down” for herbal information from their homeland! Papaya is a small tree, relatively speaking, growing to about 30 feet tall. Interestingly, it only lives for five to ten years, which is pretty short in tree years. It has deeply lobed leaves reminiscent of fig leaves (Ficus carica), hence the obvious relationship with fig’s specific epithet. Generally, Carica is dioecious, meaning the male and female flowers are on separate trees, and the tree will start bearing fruit in one year to 18 months from seed. The resulting fruit can be anywhere from three to 20 inches long and can weigh in at a hefty 20 – 25 lbs! The fruit’s skin turns from green to yellow when ripe, and the flesh is a lovely tropical yellow to orange and is filled with hundreds of wrinkly black seeds (Britannica, 2022). While most people consume just the papaya flesh or juice, there’s no need to throw those seeds away; they have a strong, pepper-like flavor and can be used as a spice in various culinary preparations.

Papaya is a small tree, relatively speaking, growing to about 30 feet tall. Interestingly, it only lives for five to ten years, which is pretty short in tree years. It has deeply lobed leaves reminiscent of fig leaves (Ficus carica), hence the obvious relationship with fig’s specific epithet. Generally, Carica is dioecious, meaning the male and female flowers are on separate trees, and the tree will start bearing fruit in one year to 18 months from seed. The resulting fruit can be anywhere from three to 20 inches long and can weigh in at a hefty 20 – 25 lbs! The fruit’s skin turns from green to yellow when ripe, and the flesh is a lovely tropical yellow to orange and is filled with hundreds of wrinkly black seeds (Britannica, 2022). While most people consume just the papaya flesh or juice, there’s no need to throw those seeds away; they have a strong, pepper-like flavor and can be used as a spice in various culinary preparations. The juice can be found in numerous commercial brands, particularly those from Latin and South America. In fact, papaya is native to Central and South America, not Southeast Asia, which may seem odd given this article is about Thai herbs. Let’s just say that papaya is well-traveled (unlike me). It has a long history of being moved from one country to another, then to another, each time being propagated, and then shipped off again to yet another tropical part of the world. The Spanish chronicler, Oviedo, first described Carica papaya in 1526 A.D. In the early 1600s, Spanish explorers to the New World carried the seed to Panama and the Dominican Republic. From the Caribbean, Spanish and Portuguese sailors carried the seeds to Southeast Asia and India, to Australia and even to Italy. Between 1800 – 1820, papaya was sent on to Hawaii, and by 1900, papaya had come all the way back to the New World, landing in Florida. In all of these locations, it was introduced as a plantation, or agricultural, crop (TFNetwork, 2016). “Papaya has become an important agricultural export for developing countries, where export revenues of the fruit provide a livelihood for thousands of people, especially in Asia and Latin America” (Evans and Ballen, 2018).

The juice can be found in numerous commercial brands, particularly those from Latin and South America. In fact, papaya is native to Central and South America, not Southeast Asia, which may seem odd given this article is about Thai herbs. Let’s just say that papaya is well-traveled (unlike me). It has a long history of being moved from one country to another, then to another, each time being propagated, and then shipped off again to yet another tropical part of the world. The Spanish chronicler, Oviedo, first described Carica papaya in 1526 A.D. In the early 1600s, Spanish explorers to the New World carried the seed to Panama and the Dominican Republic. From the Caribbean, Spanish and Portuguese sailors carried the seeds to Southeast Asia and India, to Australia and even to Italy. Between 1800 – 1820, papaya was sent on to Hawaii, and by 1900, papaya had come all the way back to the New World, landing in Florida. In all of these locations, it was introduced as a plantation, or agricultural, crop (TFNetwork, 2016). “Papaya has become an important agricultural export for developing countries, where export revenues of the fruit provide a livelihood for thousands of people, especially in Asia and Latin America” (Evans and Ballen, 2018). Today, Mexico has moved into first place as the number one exporter of papaya, with virtually all of its exports going to the United States, which “ranks as the largest importer of papayas globally” (FAO, 2021). Who knew?! So, I guess it isn’t that surprising that it was here in the United States–not Thailand–that I met Dao who shared with me about one of the most popular tropical plants in her home country, as well as mine.

Today, Mexico has moved into first place as the number one exporter of papaya, with virtually all of its exports going to the United States, which “ranks as the largest importer of papayas globally” (FAO, 2021). Who knew?! So, I guess it isn’t that surprising that it was here in the United States–not Thailand–that I met Dao who shared with me about one of the most popular tropical plants in her home country, as well as mine. According to Dao, the green (unripe) fruit is used as a vegetable to make papaya salad, and it can also be fried with meat. If boiled with meat, it makes the meat softer and more moist. The leaves, she explained, are eaten in Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos, where they are cut and fried or eaten raw. Medicinally, papaya is considered by many Thai as an old-fashioned remedy good for the body, diabetes, and cancer. The leaf juice was/is used to treat intestinal cancer, and the ripe fruit is good for relieving constipation (personal communication).

According to Dao, the green (unripe) fruit is used as a vegetable to make papaya salad, and it can also be fried with meat. If boiled with meat, it makes the meat softer and more moist. The leaves, she explained, are eaten in Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos, where they are cut and fried or eaten raw. Medicinally, papaya is considered by many Thai as an old-fashioned remedy good for the body, diabetes, and cancer. The leaf juice was/is used to treat intestinal cancer, and the ripe fruit is good for relieving constipation (personal communication). Both the papaya leaves and the fruit’s skin produce a latex substance from which a digestive enzyme called papain can be obtained. Papain is similar to the human digestive enzyme pepsin, and thus, is an effective plant-based meat tenderizer, “useful in digesting or coagulating, clotting, and converting proteins into smaller parts” (Tyler et al., 1988). (Bromelain, an enzyme from pineapples, is used similarly.) Hence, the Thai method of mixing papaya with meat effectively tenderizes the meat during the cooking process. (Note: If one has a latex allergy, caution should be used.)

Both the papaya leaves and the fruit’s skin produce a latex substance from which a digestive enzyme called papain can be obtained. Papain is similar to the human digestive enzyme pepsin, and thus, is an effective plant-based meat tenderizer, “useful in digesting or coagulating, clotting, and converting proteins into smaller parts” (Tyler et al., 1988). (Bromelain, an enzyme from pineapples, is used similarly.) Hence, the Thai method of mixing papaya with meat effectively tenderizes the meat during the cooking process. (Note: If one has a latex allergy, caution should be used.) Such uses transcend “old-fashioned” methods by including modern applications as well. Papain is used in some contact lens cleaning solutions (Tyler et al., 1988), as well as in the production of products like chewing gum, shampoo and soap, beer, in drug and anti-bacterial preparations for some digestive ailments, and in wound care. Papaya extracts are also effective in the textile industry for “degumming silk and softening of wool” (TFNetwork, 2016). In 2021, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center also noted on their website that “papaya leaves and their extracts are sold as dietary supplements to improve the immune system and increase platelet counts….A few clinical studies found benefits of papaya leaf extract in treating dengue fever and in increasing platelet counts,” though they suggested that more studies were needed.

Such uses transcend “old-fashioned” methods by including modern applications as well. Papain is used in some contact lens cleaning solutions (Tyler et al., 1988), as well as in the production of products like chewing gum, shampoo and soap, beer, in drug and anti-bacterial preparations for some digestive ailments, and in wound care. Papaya extracts are also effective in the textile industry for “degumming silk and softening of wool” (TFNetwork, 2016). In 2021, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center also noted on their website that “papaya leaves and their extracts are sold as dietary supplements to improve the immune system and increase platelet counts….A few clinical studies found benefits of papaya leaf extract in treating dengue fever and in increasing platelet counts,” though they suggested that more studies were needed. In my small world, papaya has always been “that fruit” (or juice) that I’ve never actually tried and for no particular reason. Fortunately for me, I learned something new that day–that papaya is not just a one-trick pony as I had previously thought; there are plenty of ways this plant is useful to humans, especially for people like Dao from Thailand. Having the opportunity to speak with people like her who have such personal relationships with many of the herbs we grow in the National Herb Garden never gets old!

In my small world, papaya has always been “that fruit” (or juice) that I’ve never actually tried and for no particular reason. Fortunately for me, I learned something new that day–that papaya is not just a one-trick pony as I had previously thought; there are plenty of ways this plant is useful to humans, especially for people like Dao from Thailand. Having the opportunity to speak with people like her who have such personal relationships with many of the herbs we grow in the National Herb Garden never gets old!

The powder, when combined with water, makes a jelly. The jelly is traditionally formulated with seaweed to give it a pleasant brine flavor. It is gray when seaweed is used in preparation but is white when prepared without. In Japan, the finished jelly product is called

The powder, when combined with water, makes a jelly. The jelly is traditionally formulated with seaweed to give it a pleasant brine flavor. It is gray when seaweed is used in preparation but is white when prepared without. In Japan, the finished jelly product is called  The medicinal properties of konjac come from the glucomannan in the flour, as it is a source of good carbs for gut microbiota while not being available for uptake by humans (Spritzler, 2018). Feeding gut microbiota gives konjac prebiotic properties (Spritzler, 2018). The lack of bioavailability of the glucomannan is another reason konjac is popular in keto diets (Spritzler, 2018). The glucomannan also relieves constipation and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (Fern, 2010; Spritzler, 2018). The mechanism that allows glucomannan to work as such a good source of dietary fiber is that it has a high rate of water absorption by weight, which allows for a higher water content in bowel movements (Devaraj, 2019). The prebiotic properties are due to the preference of healthy bacteria native to the gut for glucomannan over other available sugars (Devaraj, 2019).

The medicinal properties of konjac come from the glucomannan in the flour, as it is a source of good carbs for gut microbiota while not being available for uptake by humans (Spritzler, 2018). Feeding gut microbiota gives konjac prebiotic properties (Spritzler, 2018). The lack of bioavailability of the glucomannan is another reason konjac is popular in keto diets (Spritzler, 2018). The glucomannan also relieves constipation and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (Fern, 2010; Spritzler, 2018). The mechanism that allows glucomannan to work as such a good source of dietary fiber is that it has a high rate of water absorption by weight, which allows for a higher water content in bowel movements (Devaraj, 2019). The prebiotic properties are due to the preference of healthy bacteria native to the gut for glucomannan over other available sugars (Devaraj, 2019).  The spice that we call cloves comes from the clove tree,

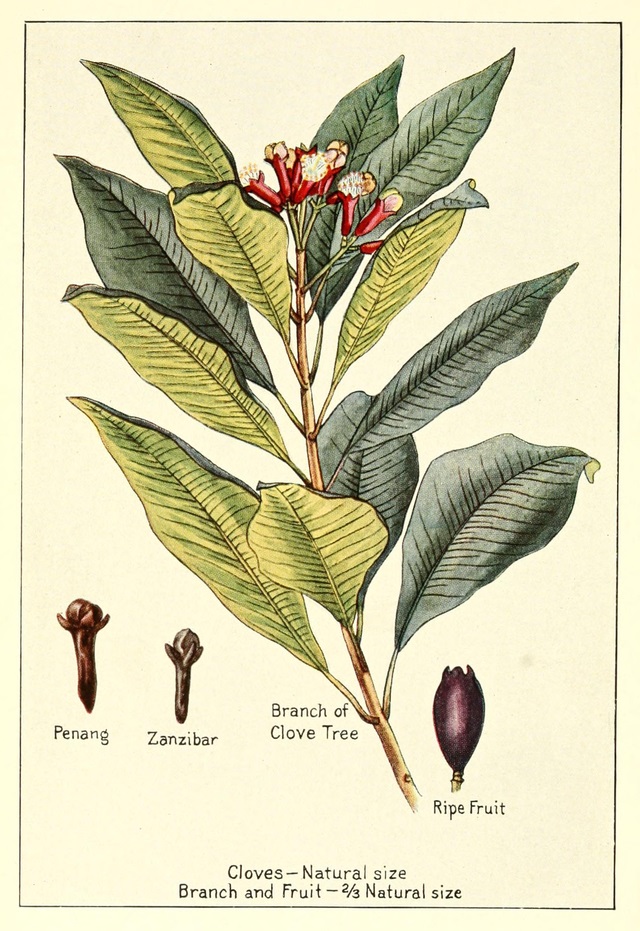

The spice that we call cloves comes from the clove tree,  The clove bud is harvested when the bud begins to turn from green to pink. The clove that we use in cooking is the stem of the flower and the round ball in the center is the unopened flower. Buds are hand-picked and dried in the sun, mostly in the fall. As they dry, the buds release a strong aroma that can be smelled from miles away. The mature fruit of the tree is called “Mother Clove” and contains a single seed. The oldest clove tree, named “Afo,” is on the island of Ternate in the Moluccas and is believed to be about 400 years old.

The clove bud is harvested when the bud begins to turn from green to pink. The clove that we use in cooking is the stem of the flower and the round ball in the center is the unopened flower. Buds are hand-picked and dried in the sun, mostly in the fall. As they dry, the buds release a strong aroma that can be smelled from miles away. The mature fruit of the tree is called “Mother Clove” and contains a single seed. The oldest clove tree, named “Afo,” is on the island of Ternate in the Moluccas and is believed to be about 400 years old.  The History

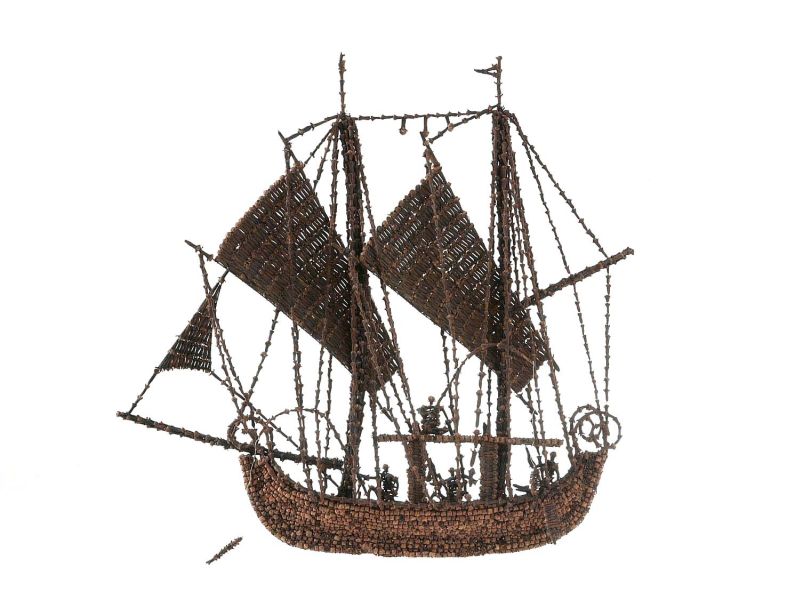

The History speaking with the emperor. Arab traders brought cloves to the Romans in the first century AD, where Galen, the famous Greek physician, used cloves in a soothing ointment (Donkin, 2003).

speaking with the emperor. Arab traders brought cloves to the Romans in the first century AD, where Galen, the famous Greek physician, used cloves in a soothing ointment (Donkin, 2003). smuggling cloves from the island punishable by death (Mosely, 2020). Today, the finest cloves are said to come from Zanzibar, and they remain an important cash crop for Tanzania. Cloves are still harvested in Indonesia, but 80% of the crop is used in the manufacture of the fragrant, domestic clove cigarette called kretek and is also used as a flavoring in the preparation of betel nut quids (Sui and Lacy, 2015).

smuggling cloves from the island punishable by death (Mosely, 2020). Today, the finest cloves are said to come from Zanzibar, and they remain an important cash crop for Tanzania. Cloves are still harvested in Indonesia, but 80% of the crop is used in the manufacture of the fragrant, domestic clove cigarette called kretek and is also used as a flavoring in the preparation of betel nut quids (Sui and Lacy, 2015).  The French stud an onion with cloves and use it when making chicken broth.

The French stud an onion with cloves and use it when making chicken broth. Artistic Use of Cloves

Artistic Use of Cloves After a brief email exchange with a colleague last fall around this same time, I set off to collect some fallen treasures from the forest floor from a tree I had never collected from before. The fruit was large and aromatic, but I was unfamiliar with its culinary use. Suddenly the sweet scent of ripening flesh let me know that the bounty was close, and true to smell, the six-inch long, bright yellow fruits of the Chinese quince

After a brief email exchange with a colleague last fall around this same time, I set off to collect some fallen treasures from the forest floor from a tree I had never collected from before. The fruit was large and aromatic, but I was unfamiliar with its culinary use. Suddenly the sweet scent of ripening flesh let me know that the bounty was close, and true to smell, the six-inch long, bright yellow fruits of the Chinese quince

So, in addition to being a delicious addition to the fall harvest, it also has an increasing number of positive side effects attributed to its consumption. Which, I believe, begs the question, when are you going to add some quince to your apple pie? There are lots of fantastic recipes on the Internet, but here is one that I tried last year after my colleague piqued my interest enough to see how they taste during fall pie season. I hope that you enjoy it as much as I did as it truly does add a lavishness and texture that I had never experienced before with a typical apple pie. I used the Chinese quince but am sure that the common quince could be used as an easy replacement. Even if you just keep a bowl of them on the counter for a sweet fragrance, I hope that you can find a way to enjoy the Chinese quince in your home this fall, too!

So, in addition to being a delicious addition to the fall harvest, it also has an increasing number of positive side effects attributed to its consumption. Which, I believe, begs the question, when are you going to add some quince to your apple pie? There are lots of fantastic recipes on the Internet, but here is one that I tried last year after my colleague piqued my interest enough to see how they taste during fall pie season. I hope that you enjoy it as much as I did as it truly does add a lavishness and texture that I had never experienced before with a typical apple pie. I used the Chinese quince but am sure that the common quince could be used as an easy replacement. Even if you just keep a bowl of them on the counter for a sweet fragrance, I hope that you can find a way to enjoy the Chinese quince in your home this fall, too!  second only to water in most consumed beverages (DeWitt, 2000). I, myself, have become a tea drinker over the years, and as a plant nerd, I wanted to know more about how the tea leaves were farmed. What I ended up learning is that while tea (Camellia sinensis) is by far the most well known and widely used product of the genus Camellia, it is by no means its only contribution to the herbal marketplace.

second only to water in most consumed beverages (DeWitt, 2000). I, myself, have become a tea drinker over the years, and as a plant nerd, I wanted to know more about how the tea leaves were farmed. What I ended up learning is that while tea (Camellia sinensis) is by far the most well known and widely used product of the genus Camellia, it is by no means its only contribution to the herbal marketplace. And finally, C. sasanqua has a long history of being used for both tea and tea seed oil in Japan, both of which go back centuries. Let us look at each of these four species in a bit more detail to better understand their contributions to both Asia and the world.

And finally, C. sasanqua has a long history of being used for both tea and tea seed oil in Japan, both of which go back centuries. Let us look at each of these four species in a bit more detail to better understand their contributions to both Asia and the world. tea production is now centered mainly in the Eastern Hemisphere, however some tea is produced in America. Several states in the U.S. have small tea growers, but most American tea is grown in South Carolina, primarily at the 127-acre Charleston Tea Plantation—arguably one of the most historic tea plantations in the country.

tea production is now centered mainly in the Eastern Hemisphere, however some tea is produced in America. Several states in the U.S. have small tea growers, but most American tea is grown in South Carolina, primarily at the 127-acre Charleston Tea Plantation—arguably one of the most historic tea plantations in the country.  used by the geisha to remove make-up and act as an antioxidant. C. japonica is famous for its anti-inflammatory activity in the field of medicine and ethnobotany. It is reported as a bioactive plant in folk medicine of South Korea, Japan, and China. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of the leaves are already reported, and this plant is proved to be a source of triterpenes, flavonoids, tannin, and fatty acids having antiviral, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities. The seeds are also used as a traditional medicine in folk remedies for the treatment of bleeding and inflammation (Majumder, 2020).

used by the geisha to remove make-up and act as an antioxidant. C. japonica is famous for its anti-inflammatory activity in the field of medicine and ethnobotany. It is reported as a bioactive plant in folk medicine of South Korea, Japan, and China. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of the leaves are already reported, and this plant is proved to be a source of triterpenes, flavonoids, tannin, and fatty acids having antiviral, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities. The seeds are also used as a traditional medicine in folk remedies for the treatment of bleeding and inflammation (Majumder, 2020). Native to China, Camellia oleifera also produces tea seed oil. It is known as a cooking oil to hundreds of millions of people in east Asia, and is one of the most important cooking oils in southern China as it has a very high smoke point of 252 degrees Fahrenheit—perfect for deep frying. It has also been used to protect Japanese woodworking tools and cutlery from corrosion (Odate, Reprint Edition 1998). Sometimes also used in soap making, it is said to add a supple conditioner for the skin. Overall, the importance of it as a cooking oil cannot be overstated for large regions of Asia, as this remains to be C. oleifera’s most valuable contribution today.

Native to China, Camellia oleifera also produces tea seed oil. It is known as a cooking oil to hundreds of millions of people in east Asia, and is one of the most important cooking oils in southern China as it has a very high smoke point of 252 degrees Fahrenheit—perfect for deep frying. It has also been used to protect Japanese woodworking tools and cutlery from corrosion (Odate, Reprint Edition 1998). Sometimes also used in soap making, it is said to add a supple conditioner for the skin. Overall, the importance of it as a cooking oil cannot be overstated for large regions of Asia, as this remains to be C. oleifera’s most valuable contribution today. Matt has worked in public gardening for a little over six years and is currently the horticulturist in the Asian Collections at the U.S. National Arboretum. He previously worked at Smithsonian Gardens in a variety of capacities. Matt is an ISA-certified arborist and an IPM manager certified with both Virginia and DC.

Matt has worked in public gardening for a little over six years and is currently the horticulturist in the Asian Collections at the U.S. National Arboretum. He previously worked at Smithsonian Gardens in a variety of capacities. Matt is an ISA-certified arborist and an IPM manager certified with both Virginia and DC. is also an evergreen, long-lived landscape tree, reaching a height of 40 to 60 feet tall and a width of up to 25 feet wide. Its pinnate leaves close up at night. The branches droop to the ground, making it a graceful shade tree. A mature tree can produce up to 350-500 pounds of fruit each year. It is native to tropical Africa and is in the Fabaceae family.

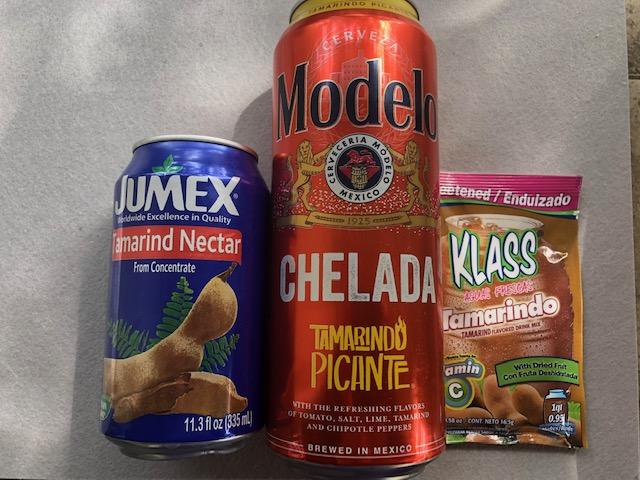

is also an evergreen, long-lived landscape tree, reaching a height of 40 to 60 feet tall and a width of up to 25 feet wide. Its pinnate leaves close up at night. The branches droop to the ground, making it a graceful shade tree. A mature tree can produce up to 350-500 pounds of fruit each year. It is native to tropical Africa and is in the Fabaceae family.  The tamarind tree grows well in USDA Hardiness Zones 10-11 and therefore, is not commonly seen in the continental United States, except in southern Florida. It produces a showy light brown, bean-like fruit, which can be left on the tree for up to six months after maturing. The sweet-sour pulp that surrounds the seeds is rich in calcium, phosphorus, iron, thiamine, and riboflavin and is a good source of niacin. The pulp is widely used in Mexico to make thirst-quenching juice drinks and even beer. It is also very popular in fruit candies. The fruit is used in Indian cuisines in curries, chutneys, meat sauces, and in a pickle dish called tamarind fish. Southeast Asians combine the pulp with chiles and use it for marinating chicken and fish before grilling. They also use it to flavor sauces, soups, and noodle dishes. Chefs in the United States are beginning to experiment with the sweet-sour flavor of tamarind pulp. Did you know that tamarind is a major ingredient in Lea & Perrins® Worcestershire Sauce?

The tamarind tree grows well in USDA Hardiness Zones 10-11 and therefore, is not commonly seen in the continental United States, except in southern Florida. It produces a showy light brown, bean-like fruit, which can be left on the tree for up to six months after maturing. The sweet-sour pulp that surrounds the seeds is rich in calcium, phosphorus, iron, thiamine, and riboflavin and is a good source of niacin. The pulp is widely used in Mexico to make thirst-quenching juice drinks and even beer. It is also very popular in fruit candies. The fruit is used in Indian cuisines in curries, chutneys, meat sauces, and in a pickle dish called tamarind fish. Southeast Asians combine the pulp with chiles and use it for marinating chicken and fish before grilling. They also use it to flavor sauces, soups, and noodle dishes. Chefs in the United States are beginning to experiment with the sweet-sour flavor of tamarind pulp. Did you know that tamarind is a major ingredient in Lea & Perrins® Worcestershire Sauce?  The fruit pods are long-lasting and can be found in some grocery stores, especially those serving Hispanic, Indian, and Southeast Asian populations.

The fruit pods are long-lasting and can be found in some grocery stores, especially those serving Hispanic, Indian, and Southeast Asian populations.  used as fodder for domestic animals and food for silkworms. The leaves are also used as garden mulch.

used as fodder for domestic animals and food for silkworms. The leaves are also used as garden mulch.  The fruit pulp is useful as a dye fixative, or combined with sea water, it cleans silver, brass, and copper. In addition to all of these uses, school children in Africa use the seeds as learning aids in arithmetic lessons and as counters in traditional board games.

The fruit pulp is useful as a dye fixative, or combined with sea water, it cleans silver, brass, and copper. In addition to all of these uses, school children in Africa use the seeds as learning aids in arithmetic lessons and as counters in traditional board games.