By Katherine Schlosser

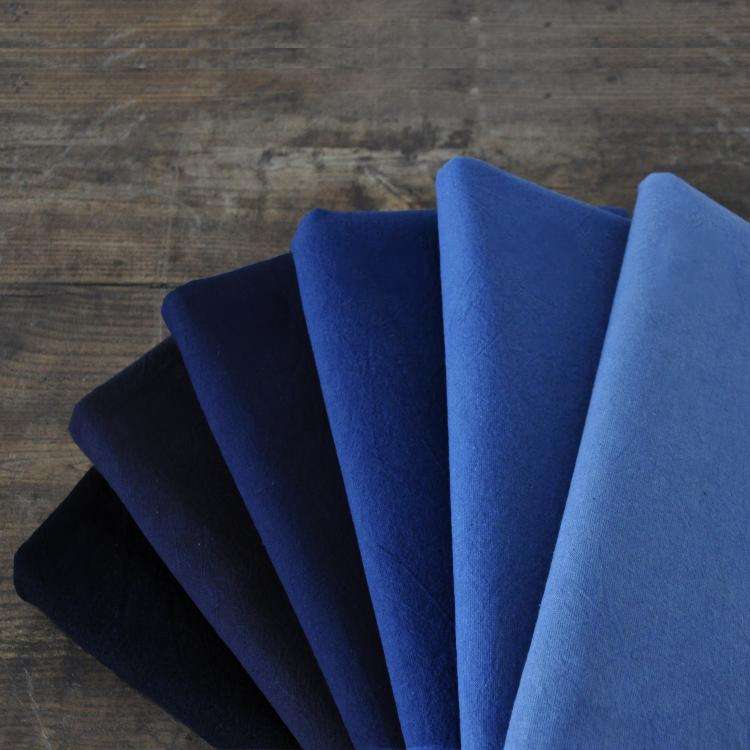

I remember the first dress that made me feel good about myself. I was 17 and looking for something to wear to a dance, not formal, not cocktail, but a Sunday dress, as we called them so many years ago. It was a slim dress (I could get away with that in those days), with three-quarter length sleeves, a prim boat neckline, and a wide shiny ribbon sash at the waist. The dress was indigo blue. I remember nothing about the boy or the dance, but I still remember the dress.

I remember the first dress that made me feel good about myself. I was 17 and looking for something to wear to a dance, not formal, not cocktail, but a Sunday dress, as we called them so many years ago. It was a slim dress (I could get away with that in those days), with three-quarter length sleeves, a prim boat neckline, and a wide shiny ribbon sash at the waist. The dress was indigo blue. I remember nothing about the boy or the dance, but I still remember the dress.

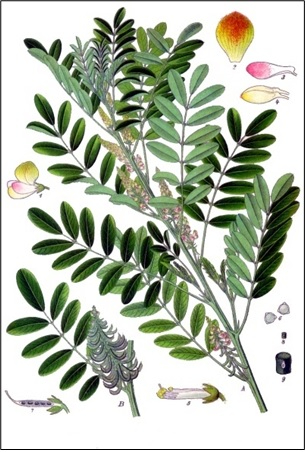

Indigofera tinctoria, indigo, a member of the Fabaceae family, has that effect on people. The dye it produces is exotic, soothing, luxurious. A color of devotion, wisdom, and justice. For all its attributes, it has also been the cause of much labor for planters, free men of color, and slaves over the years, requiring large numbers of laborers to grow and harvest enough leaves to produce the dye.

The oldest record I know of is a small piece of 6000-year-old cotton cloth on which the indigo dye is still detectable. This was discovered in a preceramic site of Huaca Prieta on the north coast of Peru during an archeological dig. Other snippets of dyed cloth, wool, and silk from archeological digs were dated 1,500 years later than those in Peru. Those others were found in archeological sites from India and Africa, to Italy, Greece and in Europe, as well as in South America.

There are other plants that produce a blue dye, especially Isatis tinctoria, woad, a primary competitor with indigo. But none have quite the same opulent quality as indigo, or the stability.

There are other plants that produce a blue dye, especially Isatis tinctoria, woad, a primary competitor with indigo. But none have quite the same opulent quality as indigo, or the stability.

Indigo grows around the globe in tropical to subtropical areas. In the United States, we have eight native indigo species, most centered in the southeast. Several will produce indigo dye but not always of top quality. Indigofera suffruticosa, also known as añil, produces a rich, stable color close to I. tinctoria, as does I. guatemalensis, or Guatemalan indigo. I. caroliniana makes a nice dye, but paler. Indigofera tinctoria, true indigo, is the best, and seeds of the plants were brought to this country in the 1700s and grown in Louisiana, Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia, and Tennessee to produce dye for commercial use.

Indigofera tinctoria can grow from 3 to 5 feet tall with light green pinnate leaves (with 4 – 7 pairs of leaflets) and sweet pink or violet flowers that bloom in July or August. In its native tropical Africa, south central Asia, Mexico, and South America, it can be either perennial or annual, or even evergreen in warmer locations. It grows best in full sun, with a little shade from the hottest part of the day, and needs regular rainfall. It also has been used in the past for a variety of medical ailments, and against insect and serpent stings or bites.

It requires 30 tons of indigo leaves (one acre) to produce about 26 pounds of pigment. Leaves are harvested, separated from stems, dried, and processed to produce the pigment. That happens after the land has been prepared, seeds planted, weeding on a daily basis (plants don’t do well when crowded), and harvested twice a year. The labor required is intense, and in the 1700s and 1800s, was usually managed by slave labor and/or free men of color.

Those who worked in the fields were subject to more than just hard work in the hot sun. Many had to endure the “putrid effluvia of the coastal swamps,” as well as stagnant pond water and mosquitoes. Disease and death was not uncommon in southern fields.

Those who worked in the fields were subject to more than just hard work in the hot sun. Many had to endure the “putrid effluvia of the coastal swamps,” as well as stagnant pond water and mosquitoes. Disease and death was not uncommon in southern fields.

Eventually, so many planters around the world were growing and exporting indigo that the market began to collapse. More than a million pounds of dye had been exported from the U.S. in 1775. In the southern U.S., cotton gained notice, along with rice, as indigo was removed and replaced. Indigo plants deplete the soil of nutrients rather quickly, so frequent labor-intense alternating of crops was necessary as well. Some planters still grew indigo but on a smaller scale.

True indigo is still grown commercially. There are artists who grow their own plants and process them to make the pigment they need for the renowned deep blue. A 5mL (.17 oz) tube of watercolor sells for $10, and a 37 mL (1.25 ounce) of oil paint sells for about $18. When you buy artwork, you are not only paying for creativity, but for materials as well!

Synthetic indigo is common now with the advantage of lower cost. As is often the case, lower cost doesn’t always mean equal products, and in this case, synthetic indigo carries the costs of diminished depth of color and damage to the environment. Unlike natural indigo, synthetic indigo is dependent on petrochemicals for processing, which are toxic and require appropriate disposal, adding to the expense. Water remaining from natural indigo processing is free of chemicals and can safely be returned to the earth.

Synthetic indigo is common now with the advantage of lower cost. As is often the case, lower cost doesn’t always mean equal products, and in this case, synthetic indigo carries the costs of diminished depth of color and damage to the environment. Unlike natural indigo, synthetic indigo is dependent on petrochemicals for processing, which are toxic and require appropriate disposal, adding to the expense. Water remaining from natural indigo processing is free of chemicals and can safely be returned to the earth.

Indigo appears in clothing, on pottery and ceramics, and on artists’ palettes. It is also in every rainbow most of us see, though not everyone can see it. In the spectrum of colors—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet—for some, distinguishing between blue and violet is difficult. Spotting the indigo is considered a sign of hope, joy, or for some, luck. With the next rainbow you see, search for the indigo and give a little thought to the human costs that brought that beautiful color to our palettes.

And think about that pretty indigo-blue dress on a shy teenage girl who sees indigo in rainbows.

Indigo species in the U.S. and the states in which they are native:

Indigofera caroliniana Mill., Carolina indigo – NC, SC, GA, FL, AL, MS, LA

Indigofera colutea (Burm. f.) Merr., rusty indigo – FL

*Indigofera decora Lindl., Chinese indigo – GA

Indigofera guatemalensis Moc. & Sessé ex Prain & Backer, Guatemalan indigo – PR, VI

*Indigofera hendecaphylla Jacq., trailing indigo – FL

*Indigofera hirsuta L., hairy indigo – SC, GA, AL, FL

*Indigofera kirilowii Maxim. Ex Palib., Kirilow’s indigo – TN

*Indigofera lindheimeriana Scheele, Lindheimer’s indigo – TX

Indigofera miniate Ortega, coastal indigo – TX, OK, KS, AL, GA, FL

Indigofera oxycarpa Desv., Asian indigo – FL (threatened)

*Indigofera parviflora K. Heyne ex Wight & Arn., nom. Inq. – AL

Indigofera pilosa Poir., soft hairy indigo – FL

Indigofera sphaerocarpa A. Gray, Sonoran indigo – NM, AZ

Indigofera suffruticosa Mill., Anil de pasto – TX, LA, GA, SC, NC, FL, PR, VI

*Indigofera tinctoria L., true indigo – NC, SC, MI, TN, PR, VI, NAV

*= non native species growing in the U.S.

¹ History of Indigo & Indigo Dyeing. Indigo History, WildColors, http://www.wildcolours.co.uk/html/indigo_history.html. Accessed 7-08-2022.

² Winberry, John J. 1979. Indigo in South Carolina: A historical geography. Southeastern Geographer. Vol. 19, No. 2, p.91-102. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44370692?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents. Accessed 08-07-2022.

Photo Credits: 1) Indigofera suffruticosa (Kohler’s Medicinal Plants, 1887, Public domain); 2) Woad-dyed fabric (Local Color Dyes, http://www.localcolordyes.com); 3 & 4) Añil-dyed fabric (Norma Schafer: Oaxaca Cultural Navigator); 5) Indigofera tinctoria (Kurt Stuber, Creative Commons); 6) Indigo-dyed fabric (Affordable-kind-craft.com.au).

Medicinal Disclaimer: It is the policy of The Herb Society of America, Inc. not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health use. This information is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an endorsement of any particular medical or health treatment. Please consult a health care provider before pursuing any herbal treatments.

References

Butler, Nic. Indigo in the South Carolina Lowcountry: A brief synopsis. Available at Charleston Tine Machine at Charleston Public Library. www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine.

de Marigny de Mandeville, Philippe. April 29, 1709. Memoir on Louisiana. Dunbar Rowland and Albert G. Sanders (ed. & trans.), Mississippi Provincial Archives, French Dominion (3 vols., Paris, 1953-1966), III, 350.

Garrigus, John. 1993. Blue and brown: Contraband indigo and the rise of a free colored planter class in French Saint-Domingue. The Americas. Vol. 50, No. 2. October 1993, pp. 233-263. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1007140. Accessed August 7, 2022.

Holmes, Jack D. 1967. Indigo in Colonial Louisiana and the Floridas. Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. Vol. 8, No. 4, Autumn 1967, pp. 329-349.

International Center for Indigo Culture, Sapelo Island, Georgia. https://www.internationalcenterforindigoculture.org/home

Kumar, Prakash. 2016. Plantation indigo and synthetic indigo: European planters and the redefinition of a Colonial commodity. Comparative Studies in Society and History. Vol. 58, No. 2, pp. 407-431. Available online: https://jstor.org/stable/43908426. Accessed 07-08-2022.

Kuta, Sarah. 2022. Cherokee Nation members can now gather plants on national park land. Good News, Smart News, Smithsonian Magazine online. April 22, 2022. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/cherokee-nation-members-can-now-gather-plants-on-national-park-land-180979965/. Accessed 07-10-2022.

Nash, R. C. 1992. South Carolina and the Atlantic economy in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Economic History Review, New Series. Vol. 45, No. 4 (Nov. 1992), pp. 677-702. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2597414. Accessed 08-08-2022.

Pattanaik, Lopa, Satya Narayan Naik, P. Hariprasad, Susant Kumar Padhi. 2021. Influence of various oxidation parameter(s) for natural indigo dye formation from Indigofera tinctoria L. biomass. Environmental Challenges 4. Elsevier B.V. Open Access, available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100157. Accessed 07-10-2022.

Rembert, Jr., David H. 1979. The indigo of commerce in Colonial North America. Economic Botany. Vol. 33, No. 2 (Apr – Jun, 1979), pp. 128-134.

Shields, Jesslyn. 2020. The dark history of indigo, slavery’s other cash crop. Available online: https://history.howstuffworks.com/world-history/indigo.htm. Accessed 08-06-2022.

Sharrer, G. Terry. 1971. The indigo bonanza in South Carolina, 1740-90. Technology and Culture. Vol. 12, No. 3 (Jul. 1971), pp. 447-455. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3102998. Accessed 08-07-2022.

Splitstoser, C., T. D. Dillehay, J. Wouters, A. Claro, Early pre-Hispanic use of indigo blue in Peru. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501623 (2016). Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/epdf/10.1126/sciadv.1501623. Accessed 09-18-2022.

The manner of cultivating the indigo plant, C.W., Charles Town, S. Carolina, 1754, The Gentleman’s Magazine, printed by F. Jeffries, etc., 1755. Available online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015020178300&view=1up&seq=248. Accessed 08-06-2022.

Katherine Schlosser (Kathy) has been a member of the North Carolina Unit of The Herb Society of America since 1991, serving in many capacities at the local and national level, including as a member of the Native Herb Conservation Committee, The Herb Society of America. She was awarded the Gertrude B. Foster Award for Excellence in Herbal Literature and the Helen de Conway Little Medal of Honor. She is an author, lecturer, and native herb conservation enthusiast eager to engage others in the study and protection of our native herbs.

Calendula officinalis is a plant in the Asteraceae family and is The Herb Society of America’s Herb of the Month for May. In my Texas Zone 8b garden, I planted calendula in November and it is now in full bloom, and will continue to bloom until the hot summer sun puts a damper on its bright yellow and orange blossoms. Planted in organic, well-draining soil, and with enough sun, this herb will reward you with its bright blossoms for a very long time. Deadheading does increase its blooms. Calendula can tolerate some freezing temperatures and it does reseed easily. I cannot imagine a garden without it.

Calendula officinalis is a plant in the Asteraceae family and is The Herb Society of America’s Herb of the Month for May. In my Texas Zone 8b garden, I planted calendula in November and it is now in full bloom, and will continue to bloom until the hot summer sun puts a damper on its bright yellow and orange blossoms. Planted in organic, well-draining soil, and with enough sun, this herb will reward you with its bright blossoms for a very long time. Deadheading does increase its blooms. Calendula can tolerate some freezing temperatures and it does reseed easily. I cannot imagine a garden without it. The Romans are believed to have named the calendula after the Latin word

The Romans are believed to have named the calendula after the Latin word  Sometime in history, it was discovered that calendula could be used as a medicinal plant. Since early times it was used as an effective treatment for skin irritations. During the U.S. Civil War, the flowers were used to stop bleeding and to promote healing of battle wounds. British garden designer Gertrude Jekyll led a campaign during World War I to raise calendula to supply British hospitals in France (Keeler, 2016).

Sometime in history, it was discovered that calendula could be used as a medicinal plant. Since early times it was used as an effective treatment for skin irritations. During the U.S. Civil War, the flowers were used to stop bleeding and to promote healing of battle wounds. British garden designer Gertrude Jekyll led a campaign during World War I to raise calendula to supply British hospitals in France (Keeler, 2016).  The petals have been used as a dye for fabrics and as an ingredient in cosmetics. Dried petals give a nice contrast color in potpourri. Some say that if the flowers are fed to hens, the resulting egg yolks will have a rich, yellow color (Barrett, 2009).

The petals have been used as a dye for fabrics and as an ingredient in cosmetics. Dried petals give a nice contrast color in potpourri. Some say that if the flowers are fed to hens, the resulting egg yolks will have a rich, yellow color (Barrett, 2009).

As an aside, Alexandra Rodrigues and associates inoculated newly created stained glass samples with fungi previously isolated and identified on original stained glass windows. They found that “fungi produced clear damage on all glass surfaces, present as spots and stains, fingerprints, biopitting, leaching and deposition of elements, and formation of biogenic crystals” (Rodrigues et al, 2014). Let that be a warning to keep your stained glass windows clean.

As an aside, Alexandra Rodrigues and associates inoculated newly created stained glass samples with fungi previously isolated and identified on original stained glass windows. They found that “fungi produced clear damage on all glass surfaces, present as spots and stains, fingerprints, biopitting, leaching and deposition of elements, and formation of biogenic crystals” (Rodrigues et al, 2014). Let that be a warning to keep your stained glass windows clean.  One of the more interesting lichens is known as Icelandic moss (

One of the more interesting lichens is known as Icelandic moss (

For those who love color AND plants, natural dyes connect you instantly to a vast range of artisanal hues that are truly vital, vibrant, and inherently meaningful through the ingredients themselves.

For those who love color AND plants, natural dyes connect you instantly to a vast range of artisanal hues that are truly vital, vibrant, and inherently meaningful through the ingredients themselves. Lavender, mint, and passionflower leaves, which are sources of natural dyes, also have soothing therapeutic properties, easing sleep and anxiety by calming stressed nerves. These plants, as well as marigold, rosemary, sage, and aloe can also create a spectrum of aromatic hues from soothing yellows, to in-between blues, greens, and gray. True color therapy through and through.

Lavender, mint, and passionflower leaves, which are sources of natural dyes, also have soothing therapeutic properties, easing sleep and anxiety by calming stressed nerves. These plants, as well as marigold, rosemary, sage, and aloe can also create a spectrum of aromatic hues from soothing yellows, to in-between blues, greens, and gray. True color therapy through and through.  Working with natural color can be a way to forage for beautiful natural hues and to connect with your local ecologies, even in your own backyard or urban sidewalk. When working with a landscape, consider what is abundant, in season, accessible, and even invasive. Wild fennel – seasonally abundant on the West Coast or in summer gardens – can be quite an aggressive plant in the landscape (even on urban sidewalks!) making it a wonderful and seasonal dye to gather. Collecting fennel flowers and fronds at their peak or just after provides the brightest hues. Wild fennel can create gorgeous fluorescent yellows from both the fronds and blooms.

Working with natural color can be a way to forage for beautiful natural hues and to connect with your local ecologies, even in your own backyard or urban sidewalk. When working with a landscape, consider what is abundant, in season, accessible, and even invasive. Wild fennel – seasonally abundant on the West Coast or in summer gardens – can be quite an aggressive plant in the landscape (even on urban sidewalks!) making it a wonderful and seasonal dye to gather. Collecting fennel flowers and fronds at their peak or just after provides the brightest hues. Wild fennel can create gorgeous fluorescent yellows from both the fronds and blooms.  Aloe, a succulent whose soothing leaf gel helps to heal burns, keep the skin hydrated, and offer UV protection from the sun’s powerful rays, can also make calming color palettes. Aloe is used as a plant dye in many areas of South Africa, where the roots are most often used to dye wool red and brown. From the leaves you can also make luminous soft yellows and pinks—without the use of any additional mordant.

Aloe, a succulent whose soothing leaf gel helps to heal burns, keep the skin hydrated, and offer UV protection from the sun’s powerful rays, can also make calming color palettes. Aloe is used as a plant dye in many areas of South Africa, where the roots are most often used to dye wool red and brown. From the leaves you can also make luminous soft yellows and pinks—without the use of any additional mordant.

By Maryann Readal

By Maryann Readal If you are a bird lover, you will probably recognize safflower seed as an ingredient in some birdseed. If you grow safflower in your garden, your garden will attract a variety of song birds, including chickadees, finches, nuthatches, woodpeckers, mourning doves and cardinals, who love the safflower seeds. Safflower seeds are oblong shaped and a bit bitter, making them not attractive to bird-feeder bullies like grackles, starlings, and squirrels.

If you are a bird lover, you will probably recognize safflower seed as an ingredient in some birdseed. If you grow safflower in your garden, your garden will attract a variety of song birds, including chickadees, finches, nuthatches, woodpeckers, mourning doves and cardinals, who love the safflower seeds. Safflower seeds are oblong shaped and a bit bitter, making them not attractive to bird-feeder bullies like grackles, starlings, and squirrels. Remember the fizzy tablets you dropped in the vinegar to dye those vibrantly colored Easter eggs? Try something new this year. Dye those eggs with all natural products found in your garden or kitchen. This is a fun project with interesting results; and the kids will love to experiment with the different items. The environmental issues aside, you won’t be using artificial dye to transform the eggs into beautiful masterpieces.

Remember the fizzy tablets you dropped in the vinegar to dye those vibrantly colored Easter eggs? Try something new this year. Dye those eggs with all natural products found in your garden or kitchen. This is a fun project with interesting results; and the kids will love to experiment with the different items. The environmental issues aside, you won’t be using artificial dye to transform the eggs into beautiful masterpieces.

Author Chris McLaughlin shows readers how to use botanicals to dye fiber and fabric in her book A Garden to Dye For (St. Lynn’s Press, 2014, $17.95). Her palette includes the obvious and the obscure. Indigo and madder root are well documented. But, did you know the properties of pokeberry, mint, bee balm, purple basil, marjoram, tansy? Check out Chris’s book and learn to coax color from nature.

Author Chris McLaughlin shows readers how to use botanicals to dye fiber and fabric in her book A Garden to Dye For (St. Lynn’s Press, 2014, $17.95). Her palette includes the obvious and the obscure. Indigo and madder root are well documented. But, did you know the properties of pokeberry, mint, bee balm, purple basil, marjoram, tansy? Check out Chris’s book and learn to coax color from nature.  How did you get interested in using plants for dye?

How did you get interested in using plants for dye?